When Michelle Yeoh took home an Academy Award for her performance in "Everything Everywhere All At Once" she made Oscar history as the first Asian to take home the Best Actress Award. But will that make a difference in how Hollywood sees Asians on screen?

Michelle Yeoh has been a superstar in Asia for decades, but Hollywood was slow to recognize her talent and potential. It noticed her in "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon," then could not ignore her or the later box office success of "Crazy Rich Asians." But last year it could not resist the demands of the multiverse as Yeoh racked up award after award for her work in "Everything Everywhere All At Once."

Yeoh made clear how she felt about Hollywood when she accepted her Golden Globe award for Best Actress in a Comedy or Musical: "I remember when I first came to Hollywood, it was a dream come true until I got here because, look at this face, I came here and was told, you are a minority. And I'm like, no, that's not possible. And then someone said to me, 'You speak English?' I mean, forget about them not knowing Korea, Japan, Asia, India. And then I said, 'Yeah, the flight here was about 13 hours long, so I learned on the way.'"

Brian Hu is the artistic director at Pacific Arts Movement. He programs the wildly diverse films at the currently running Spring Showcase as well as the larger San Diego Asian Film Festival in the fall.

"I'm pretty cynical about the Oscars," Hu said. "I guess, because I've seen plenty of times where Asian people — or all minorities — where they win and we can hail it as a moment and then nothing really changes."

But on a personal level, the win did mean something.

"I grew up watching her because my parents were Chinese immigrants who rented VHS tapes of Hong Kong martial art films. And she was in so many of them," Hu recalled. "And I would never have thought that any star from those Hong Kong movies would ever have this moment. For me, it is not just about race. It's not just about an Asian person won. It's about something from my own life won. And I think that is what is so moving about it."

'Yellow peril' and oriental exoticism of early Hollywood

As someone of Asian descent, I have always been fascinated by how Asians have been depicted on screen. Films like 1932's "The Mask of Fu Manchu," with Boris Karloff as the title villain, channeled the fear many Americans had for "foreigners," but it also revealed the fascination the public had with the exotic "Orient." Karloff's Chinese character is used as a stock villain, but there are occasional surprising moments regarding Fu Manchu when it's revealed he received education at three prestigious universities or when he expressed legitimate outrage at the pompous British and threatens an Asian rebellion.

These hints of interest to more layers of the character are not enough to gloss over the negative racial stereotypes, but they are enough to argue against the erasure of such films because they reveal where we came from as a society; we cannot see how far we came or how far we still need to go without having these films available and viewed in a broader context.

Hu points out, "It's like Hollywood is obsessed with Asia during this time. There are so many movies that are set in Asia. I mean, they're usually like the b-films, including Charlie Chan movies. But, America was very interested in geopolitics of what was happening in Asia, because America was a part of it in terms of World War II. So many films in 1940s and '50s are about Asia because that's who we were fighting. Because of Korea, because of all these people who are in the military, who are stationed in the Pacific Islands — bringing back stories of the Pacific Islands. And so it was on the mind. In some ways, I feel like we're not even back at that level yet in terms of the kind of films produced by Hollywood that are about Asia. That said, it was not a pretty picture because these films may have been about Asia, but they didn't star Asian people. So I think with Michelle Yeoh's victory it was really a way of Hollywood saying, 'We're interested in Asian stories and you can even play the main characters, and you could do it with dignity and with humanity.'"

Crass caricatures of the 1960s and beyond

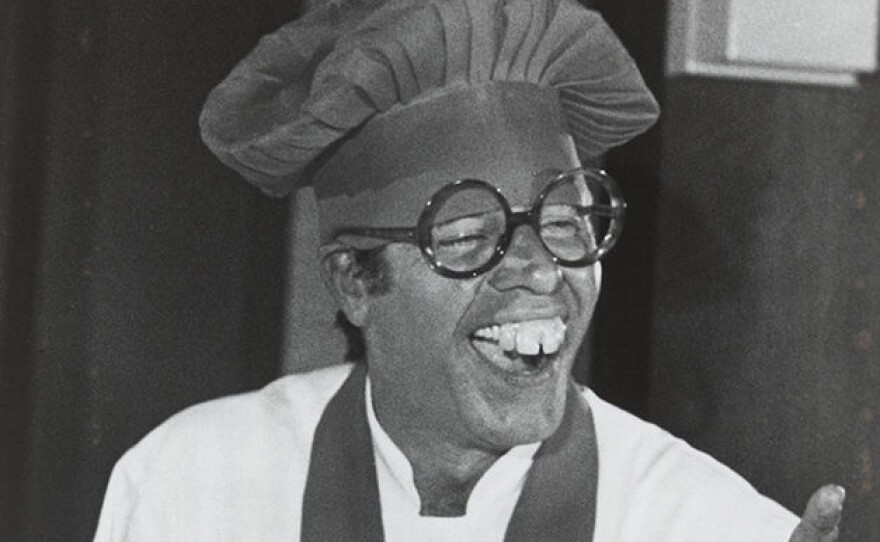

But "The Mask of Fu Manchu" and Charlie Chan films had a very different tone from the crass negative stereotype Mickey Rooney gave audiences decades later in 1961with "Breakfast at Tiffany's." This was the 1960s, we were heading into the Civil Rights movement, Hollywood should have known better than to serve up such an offensive caricature. But then Jerry Lewis offered a similar Japanese caricature almost two decades later in "Hardly Working." These are just a couple more of the egregious examples of Hollywood's depiction of Asians.

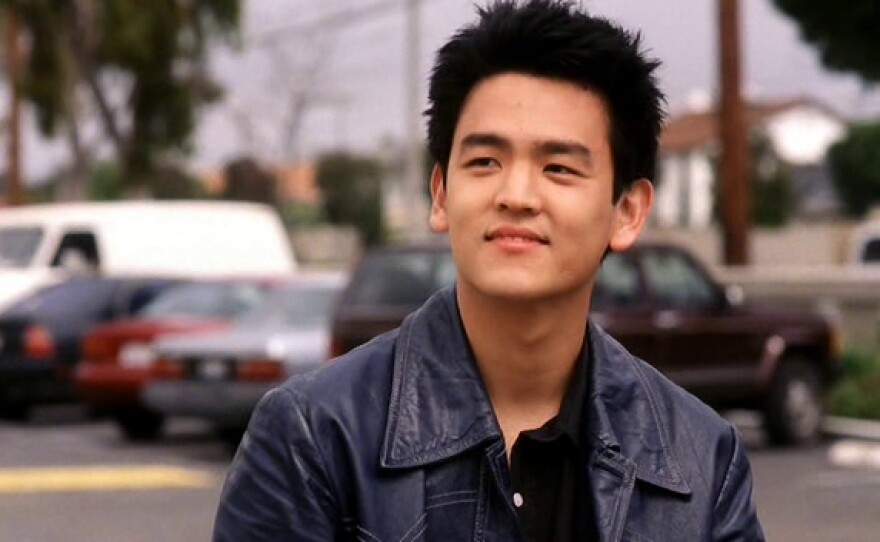

But "Everything Everywhere All At Once" also reminded Hu of something else. Ke Huy Quan, who won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for that film also famously played Short Round in "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom."

"When people ask me about the worst instances of Hollywood racism, I have to remind them that in 1984 — like in my lifetime — Steven Spielberg, of all people, made 'Indiana Jones in the Temple of Doom.'" Hu said. "There's something about Indy that's always been a little bit like American hero going all over the world: 'I own this place. I tell you what to do with your archaeological artifacts.' And he goes to, I think China first, and they're serving snake and monkey brains, just like stereotypes of East Asians will eat anything. I mean, there's a very short line between that and COVID conspiracy theories and wet markets and things like that. That's not even the end of 'Indiana Jones Temple of Doom,' then they go to India, and then all bets are off. It's like India is a country of demons. That's how this film portrays India, where people are ripping hearts out of chests."

But the film also gave the young Hu a character who looked like him.

"I grew up loving 'Indiana Jones in the Temple of Doom.' I mean, I was a kid, and this contained probably the only person who was my age who looked like me, like a young Asian boy and that was Short Round," Hu explained. "He spoke with an accent. I didn't speak with an accent, but whatever. He was really fun and charming, and he was Indiana Jones' sidekick. Who wouldn't want to be that as a little kid? And so, yeah, the ways in which the movies are so seductive, right? That I can hold in my mind both the fact that this is such a grotesque caricature of so many Asians, but also my certain kind of fondness of the movie because of how it shaped who I am. Hollywood's complicated, and it's complicated, and it's gotten away with a lot of horrible representations."

Indie films from Asian Americans signal a change

Just before the pandemic, Hu did a list of the 20 best Asian American films of the past two decades for the L.A. Times. The list emphasized that real change comes when you get Asian Americans actually writing the scripts and directing the films and casting the roles and seeing the creative vision all the way through.

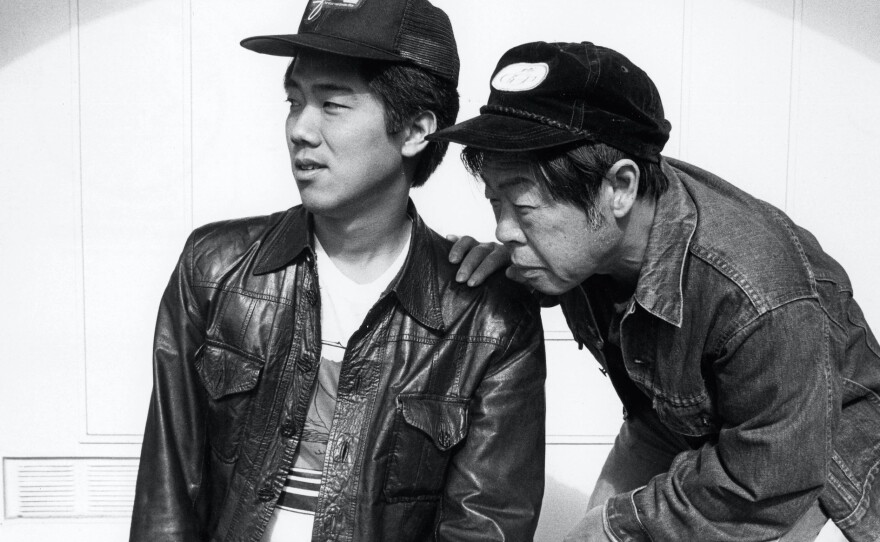

Films such as Wayne Wang's "Chan is Missing" in 1982 and Justin Lin's "Better Luck Tomorrow" in 2002 are key moments signaling a change in how Asians were changing how they could be seen on the screen.

Hu has been showcasing the diversity of these images through international filmmakers and perhaps more importantly, through Asian American filmmakers through his programming.

"This is what I do at the San Diego Asian Film Festival, is get to know these young, and maybe not so young Asian American filmmakers who they've learned the lessons of 'Better Luck Tomorrow,' and they're sort of been freed by that film to explore other kinds of directions," Hu said. "I love the work of Andrew Ahn. For instance, he made a film called 'Spa Night,' which is about sort of a gay Korean American man in Koreatown. But then he switches to this beautiful, heartwarming drama called 'Driveways,' there was a script going around, and they were looking for a good filmmaker. So they got Andrew Ahn, and Andrew said, can we just make the characters Asian? And they said, 'Why not?' So I love that Andrew Ahn is proving that an Asian American filmmaker can be so many different kinds of filmmakers all at once."

You can enjoy the Spring Showcase through Thursday at the UltraStar Mission Valley Cinemas or seek at any of the films discussed on your own.