Keolu Fox stands on a balcony overlooking a cloud-covered Pacific Ocean on the edge of the UC San Diego campus. He said he is blessed to work at a university that excels in genetic research, where the ocean’s a stone’s throw away and the surfing is pretty awesome.

Though not as good as at his family’s home in Hawaii.

Fox is a genetic scientist and a native Hawaiian who is using DNA to learn how his ancestors, his "Kupuna," moved from one Island to the next. Risky exploratory trips that he compares to "moonshots."

Fox believes the journey ultimately brought Polynesians to a pre-Columbian landing on the North and South American continents.

"It’s traveling thousands of miles across our planet’s oldest, most gnarly, most dangerous ocean. And being completely happy with that process," said Fox, who is also a professor of anthropology at UCSD.

"You find comfort in reading the stars at night. You find comfort in understanding winds and currents like this. You find comfort in reading this ecological metadata that allows you to know the direction that you’re going.”

The ability of ancient Polynesians to navigate to far-off solitary islands in the vast Pacific Ocean might seem unfathomable to a modern person.

Fox said you need to understand the intimate relationship, and the deep knowledge the Polynesians had of the ocean and the maps provided by the stars in the sky.

"You would use the green glint on the bottom of a cloud from the reflection of a lagoon below it to understand that there is land ahead," he said. "Currents are very important. The different pitches of the boat itself … and once you have a Venn diagram of all these different forms of data, you can understand directionality."

As a member of the Polynesian diaspora, Fox speaks with one foot in the oral traditions of his people and another foot in the world of social and genetic science.

"It’s true that our grandparents told us we came from Tahiti. But now I can show you in an unbiased way that we have another thing we can be proud of. And that is that we’re the greatest voyaging and seafaring people in human history," Fox said.

The way of migration

Some evidence of the Polynesian migration is pretty obvious. It’s found in the similar languages people speak.

But what’s not been clear is the path the migration took. Fox said the island-hopping started at the Bismarck Archipelago, near Papua New Guinea, and moved east at least as far as Rapa Nui, better known as Easter Island.

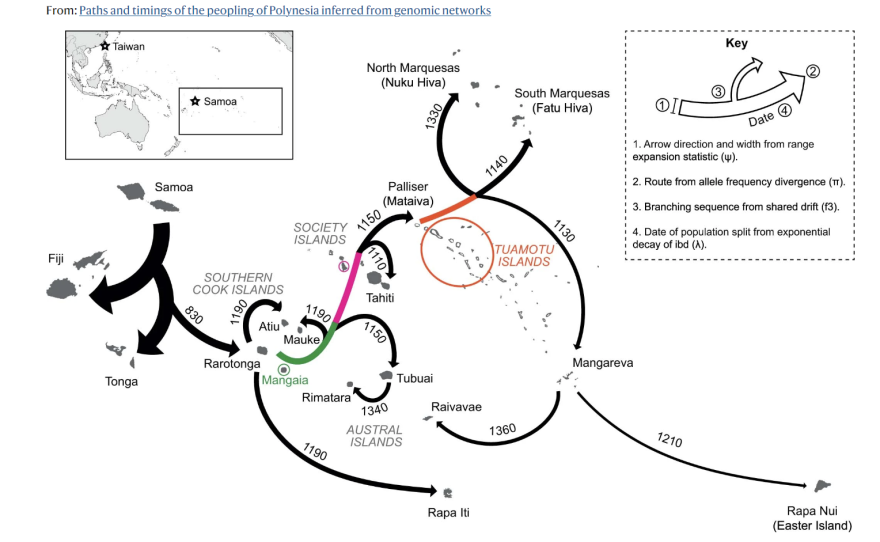

But analysis of DNA by Fox and his research group has been able to draw a map, and establish a timeline for that migration. They have used methods similar to analysis of animal migrations, observing how their genomes change as they move from one place to another.

A paper published in the journal Nature three years ago presented a specific westward migratory path. Fox was a co-author. Testing the genome of people on one island and comparing it to those on islands settled by their descendants or forebears, They can understand the sequence of island settlement.

Alex Ioannidis, another co-author on the Nature article, said you have to look at the way their genetic traits evolved as smaller groups broke off and moved to a different place.

"Imagine that on the original parent island, from which they came, let’s say there were only one in a hundred people with red hair. But on the new island, if one of the 10 people on that boat had red hair, then on the new island you’re going to have a 10% frequency of red hair. Right? So you’re going to have this strong effect, depending on what the founders happened to have,” said Ioannidis, a computational geneticist at UC Santa Cruz.

He said red hair is just one illustration. There are millions of genetic traits across the genome that can be analyzed in this way.

Add some more genetic analysis and a lot of mathematics, you can find out how long ago these settlements took place. Evolution of DNA lets you calculate how many generations separate the people of Tahiti from their distant cousins in Hawaii.

Did they make it to America?

Given the speed and the size of the Polynesian eastward expansion, why didn’t they end up in America? If they found a little place like Easter Island in the South Pacific, how could they miss a whole continent?

Keolu Fox said they didn’t. And they arrived hundreds of years before Columbus.

"The reality is that the nail is in the coffin, baby,” Fox said. “The idea that our Polynesian ancestors made it to South America first is a fact."

Genetic evidence from modern descendants clearly shows some Polynesian islanders share the same genetic signature seen in at least one South American Indian tribe. The history of Polynesian expansion shows the time of their furthest eastern progress coincides with their contact with South American Indians.

"The settlement process of the remote Islands all the way out to Easter Island, the most remote, was occurring right around the time, the 1100’s and 1200’s, that we date the contact with the Native Americans to have also occurred,” Ioannidis said.

Other evidence suggests a Polynesian landing on the coast of South America, including the introduction to the continent of the chicken, an Asian and Oceanic bird. Still, some doubt remains because, so far, no Polynesian DNA, from that era, has been found in South America.

Ioannidis said the possibility that an Indian boat made it to a south sea island to initiate the contact cannot be discounted. But Fox called that scenario "highly unlikely," given how little evidence we find of Native American navigational skills or their construction of ocean-worthy vessels.

Besides, searching for evidence of ancient Polynesian DNA on a huge continent with a large population like South America isn't easy.

The researchers continue to study this history to answer the unanswered questions. Fox wants to bring genome testing to North America, in hopes that indigenous tribes along the California coast will offer samples to see if they may be linked to the Polynesian people.

"The idea of testing a hypothesis that brings indigenous people closer together around unity and connectivity and harmony and balance and says that we had a relationship before settler colonialism,” Fox said. “I think that’s a really powerful thing.”