It looks like one side of a duck. And grid operators call it the duck curve.

If you trace the net daily demand for energy in California it starts at midnight with the tail, then it follows the belly of the duck down to nearly zero at midday, when solar energy production is at its peak.

But then demand, called load, ramps up to form the head of the duck in the early evening, when demand for energy is highest and the sun is setting.

“So in the belly of the day — you know that noon to 3 p.m. — is the deepest part of the belly, where our net load is at its lowest because of our output from renewable resources,” said Brian Murray, director of real time operation with the California Independent System Operator (ISO).

Net load is total demand minus energy provided by solar and wind.

Murray said the duck curve represents the challenge of meeting demand in a world of renewable energy, which varies from one hour to the next and cannot be produced just by throwing a switch.

And when he talks about renewables, he mostly means solar power, which provides most of California’s electricity during daytime in the summer. He said while the state maintains 20,000 megawatts of solar capacity, there’s only 8,500 megawatts of wind energy.

But as technology and construction move ahead, things will change.

“Off-shore wind … That’s in the planning horizon for us,” Murray said.

And then there are battery farms. Murray said the growth of that energy source has been “exponential.”

“Batteries have been a major player for us in terms of their flexibility, right? It’s not like a steam plant that needs ten hours to turn on,” Murray said.

“Batteries are essentially always on. They can be discharging and providing energy to the grid, or they can be consuming energy while they’re charging. They are beneficial in multiple areas of the duck curve.”

Flexibility is the key to running a modern energy supply operation that's moving to renewables, as state law requires California to do.

When one source is not producing energy, you have to switch to another. When you have more energy production than you can use, you can export it to another state or use it to charge battery installations for later use.

California is one of 13 states in the Western Energy Imbalance Market (WEIM) that allows states to purchase energy from others in the region.

As California ISO tries to optimize flexibility in its supply, a new project at UC San Diego seeks to do the same with energy demand.

Programming everything from printers to AC units

In a low-slung building just below the trolley tracks at UCSD, engineering researchers lead us through rooms filled with computers, breakers and nodes. The nodes are small boxes that communicate with electric devices on campus.

The new building is the hub of an energy test bed that will study a big piece of the campus to learn how electronic devices can be turned on and off to make the most of energy supply.

“You have water heaters. You have electric vehicles. You have air conditioning systems. You have a small printer. So we are looking at thousands of devices that are spread throughout the campus,” said Professor Jan Kleissl, the principal Investigator for the project called DERConnect.

“And we picked those that are ready to reduce load or increase load and then communicate with them and make them run faster or slower, depending on what we need.”

Testbed project manager Keaton Chia said the energy demand side is constantly in flux.

“So how do we manage the coordination? How do we make these distributor devices smart enough to actually talk back and communicate essential information back to each other so we can maintain that balance between generation and load across the whole grid,” Chia said.

One example of a smart device is a building sensor, that can tell the grid there’s nobody on the floor of a building. The building can therefore be programmed to turn off the lights or suspend air circulation on that floor.

The UCSD testbed, like the California grid, also has batteries that can store energy and, if you want, generate energy to simulate a wind power station.

“Because of that variability we need to look for flexibility and variation on the load side,” Chia said. “And that way we can work together, customer and generator/provider to maintain that balance.”

A primary goal at UCSD is to create a set of algorithms to program electrical devices so the grid will supply power where demand actually exists.

Renewable energy goals for California ISO

The political forces driving changes to California’s electrical grid are state laws that demand greater use of renewable energy.

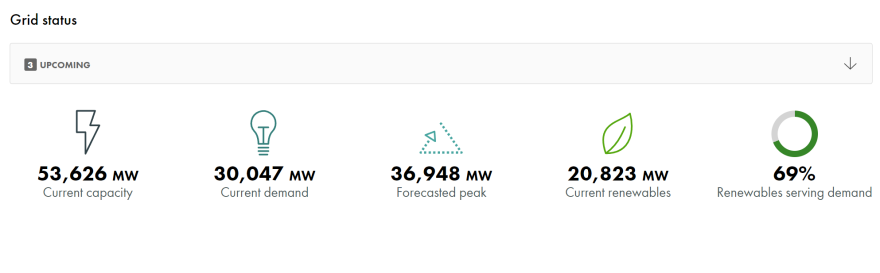

Murray, with California ISO, said the state’s power supply has to be 60% renewable energy by 2030 and 100% by 2045.

That means patching the state’s energy shortfalls, where renewable resources don’t meet load requirements, such as the one represented by the head of the net load duck, between 4 and 9 p.m.

Murray said the flexibility provided by the state’s expanding battery farms are already making a difference. He uses the example of a 200 megawatt battery facility.

“These batteries can oscillate from full discharge to full charge in one automatic generation control cycle. So in four seconds, this 400 megawatt oscillation is possible,” he said.

Can California meet its renewable energy goals? Murray said yes it can.

“We’ve got a number of days where we’ve produced 100% of our load by renewables. So to say can we produce 60% by 2030? Absolutely. We’re pretty close to that already,” Murray said.

Nuclear energy is also clean energy since it doesn’t emit greenhouse gasses, But Murray says the nuclear power generation schedule is very inflexible since it’s so difficult to reduce the output or shut it off.

So with the growth we’re seeing in other clean energies, he doesn’t think nuclear will be needed in California’s future.