Certain earthquake fault segments long thought to be stable may rupture and cause a mega-quake, suggests a new study.

That's what happened during the 2011 magnitude-9 quake in Japan that triggered a tsunami and during the 1999 magnitude-7.6 Chi Chi quake in Taiwan. In both cases, scientists assumed that "creeping" sections of a fault would serve as a buffer and prevent the entire fault from unzipping. But a new study published online Wednesday in the journal Nature suggests this may not always be the case.

Combining computer modeling and fieldwork, researchers at the California Institute of Technology and Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology found that creeping segments sometimes snapped, resulting in a bigger quake than anticipated.

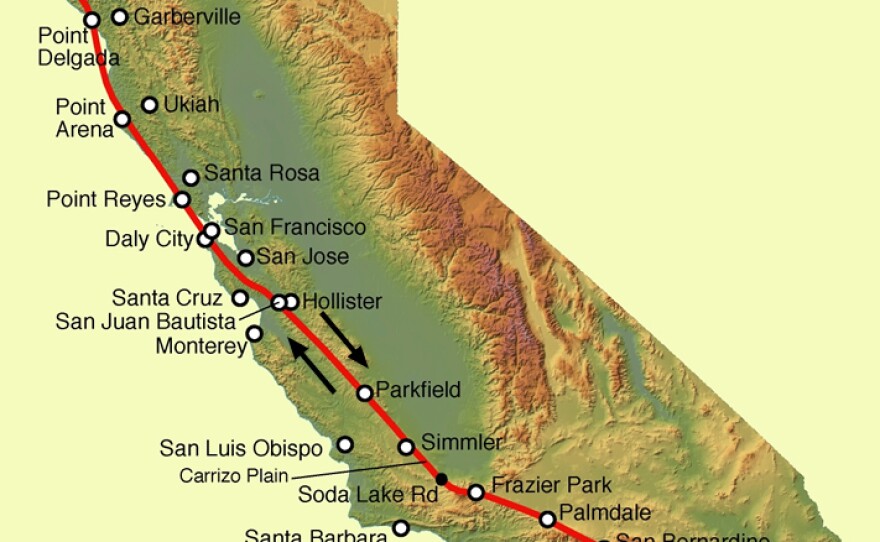

This may have important implications for California's San Andreas Fault, which has a creeping section that separates the locked segments in Northern California and Southern California.

Scientists previously theorized that a wall-to-wall San Andreas quake may be possible, though that's still under debate.

Caltech geophysicist Nadia Lapusta told the Los Angeles Times that the San Andreas may not necessarily behave exactly like what computer models predict.

"Hopefully the creeping segment is such that it doesn't have the propensity for weakness. But without examining further, you can't say," she said.

More research may include drilling into rocks surrounding the fault to collect samples and examining a fault close to the surface. Scientists previously said California faces an almost certain risk of being rocked by a strong earthquake - magnitude-6.7 or higher - by 2037. The odds of such an event are higher in Southern California than Northern California. U.S. Geological Survey geophysicist Kenneth Hudnut told the Times it was unlikely that a quake would race through the middle section of the San Andreas.

If a mega-quake occurred, it would place a burden on emergency responders, said Hudnut, who had no role in the research.