T.J. Tallie came to the Lambda Archives in the fall wanting to know what it was like to be Black and LGBTQ+ in San Diego in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

One person burst through the file boxes, a spitfire barely over five feet sporting big glasses: Marti Mackey.

“In her day, Marti Mackey was deeply inspirational and profoundly irritating. I think that is all one could ever hope to be,” said Tallie, an Associate Professor of African History at the University of San Diego.

Mackey arrived in San Diego in 1988. She was 38 years old.

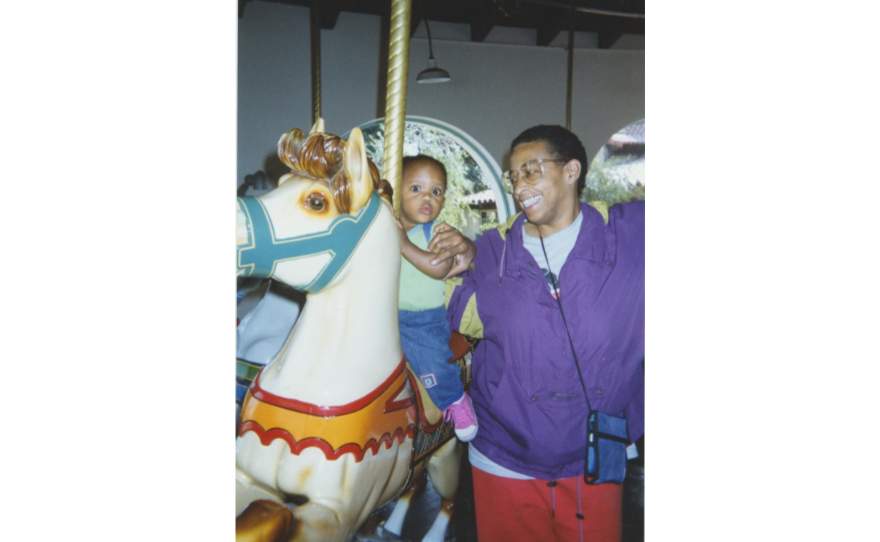

The story — which Tallie is careful to say he hasn’t fact-checked yet — goes that her car broke down and she decided to stay for a little bit. But she fell in love with the city, and with Phyllis Jackson.

Tallie describes Jackson, also a Black lesbian, as a dedicated mother and brilliant activist who had worked in drug recovery programs.

“So they became quite a team,” he said. “In a larger group together, their love story also becomes a story of activism.”

By later that year, Mackey was writing for a local gay and lesbian publication.

“Prior to 2010, the best way that you knew what was happening in the queer community was through local newspapers,” Tallie said. “They were free. They pointed out where any of the bars or community services were. They also had plenty of opinion pieces. Before the internet and smartphones took that public space, newspapers were our public space.”

Mackey quickly became one of the most popular and controversial writers.

She called herself a member of the “Anti-Fluff Brigade.” She thought the U.S. — San Diego especially — loved to highlight the positive, but glossed over all the work left to do.

With her columns, Mackey scrubbed off the gloss.

“She writes with brilliant urgency. She doesn’t hold punches,” Tallie said.

She wrote what sound like modern day proverbs: “Keeping your mouth shut only makes you run your tongue around the bad taste inside.”

She wrote about the Gulf War: “We fill our gas tanks with the blood of the children who were slaughtered ‘over there’ and laugh because the price is so low.”

She wrote about the 1992 LA Riots: "I can forgive you only if your foot finally is released from my throat. I can forgive if I stand here from a position of power and to powerlessness. I can forgive if we are able to stand toe to toe, eye to eye, for then and only then can forgiveness have any significance. Until the day of liberation comes and my need to be free is attained, there will be no forgiveness. There will be nothing to forgive.”

She called out structural racism and misogyny within the LGBTQ+ community: “It’s a white mans’ world. Even the gay and lesbian community thinks so, especially in how they mimic him.”

People called her a troublemaker.

She responded: “I mean, if you’re stepping on my foot and I tell you to get off, should I be called a troublemaker for not letting you stand on my foot?”

The archives are filled with hate mail to Mackey — and her comebacks.

“In response to a three-paragraph letter that was deeply white supremacist and said that Black people had no intellectual ability and had no business writing, she just simply wrote, ‘I give it a D. It's got a beat, but you can't dance to it.’ And I live. When I saw that, I screamed. I screamed in the archive,” Tallie said.

Mackey founded a group called LAGADU: Lesbians and Gays of African Descent United. Tallie said it was the first formal, sustained organization of its kind locally.

“Not only did LAGADU create a space for Black LGBTQ San Diegans to say, ‘Oh, my God, I'm both of these things,’ right? But it also really took up space in Pride and in Hillcrest in general,” he said.

LAGADU ran a sober space at the Pride parade, connected people to treatment resources for HIV/AIDS and drug addiction and held what they called “rap sessions” for Black LGBTQ+ San Diegans to talk.

“They're like, ‘Look, it's been hard here. How do I navigate racism at the bars? How do I navigate employment? How do I navigate these relationships?'” Tallie said.

Two of LAGADU’s members marshalled the 1990 pride parade. Mackey put on a show about Black LGBTQ+ life at the Lyceum Theater downtown. They created big moments of visibility for a tiny demographic in San Diego.

In 1991, Pride named Mackey Woman of the Year.

“She gives this beautiful speech where she's like, ‘I don't know why you all want me. I'm just a troublemaker that writes what I see, but I guess this means that I got to keep on doing it,’” Tallie said.

Tallie said Mackey made him feel less alone. He’s Black and queer and 40. He calls her his “historical bestie.”

“It is shocking to think that in four years, she could do all of that,” he said.

After only four years in San Diego, in August 1992, Mackey’s weekly column begins disappearing from the archives. Fundraisers for her medical bills start appearing in October. Sign-up sheets for her care list dozens of names. In December, obituaries. She died of cancer at 42.

It was just a month after Audre Lorde, another Black lesbian writer, died of cancer. One local publication ran their obituaries side by side. They were hard losses at a time when the AIDS crisis was robbing the LGBTQ+ community of so many leaders.

Decades later, it felt like a loss to Tallie, too.

“One of the things that's hardest about being a historian in the archives is that you get very invested in the material, you get very invested in the people you read about,” he said.

“There is this moment when you keep following and you accidentally move a month ahead, and then there's nothing, and you have to go back, and someone that you have grown to care about is no longer there.”

Searching through the past, Tallie said he found hope for the future.

“I came here to do, you know, an investigative historical thought about what it meant to be Black and queer in San Diego, and I found a hero,” Tallie said.

After a pause, he grinned.

“What is wild about that is that Marti would be wildly uninterested in any of this. She would look at me and be like, ‘All right, so what are you doing?’ Just be like, adjusting her glasses and be like, ‘So what are you doing? Is it, is it better? Oh, we got phones now. We got phones now that do all that? Fixed poverty? Did it fix the AIDS? No? Still got wars? They're still racist out here?’ And I think that then she'd be like, ‘Okay, well, then stop praising me and go get to it,’” he said.

Tallie said Mackey’s words still resonate.

“When she writes about structural racism, when she writes about politicians that don't care about the everyday lives of people or drum up easy scapegoats to win votes but don't want to make changes. She says in 1991, ‘I live in the heart of Hillcrest, and it is a place where I hear the homeless constantly growing and nobody can afford to live here, and the place is crowded and expensive, and what are we going to do about it?’ She could have said that on Thursday,” Tallie said. “There is something deeply reassuring and also so horrifying that most of the things that she wrote about are unchanged.”

He said the renewed push for social justice following George Floyd’s murder in 2020 gave hope that “we could talk about stuff and people would listen. But I think in the last five years, we may have gotten a little fatigued. We may have seen that the world is more complicated than that.”

“I think Marti would say, ‘Oh, so people listened for a minute, and then they got tired. Work is still the same,’” he said.

As the new administration recognizes only two genders, bans trans people from serving in the military and ends federal diversity initiatives, Tallie leans on Marti.

“I am overwhelmed that I am just one person, and I am deeply flawed,” he said. “But so is Marti Mackey. And maybe that gives me hope.”

Tallie curated a digital archive of Mackey’s life. The Lambda Archives plans to make it available to the public in April.