Tarbox Street in Encanto is noisy with roosters and dogs. A few lots from the end, sits a small home with a big backyard. A yellow sign hangs on the fence: “Encanto Says No.”

Thiago Batista lives next door. He noticed people moving large appliances, so he pulled the permits for the lot.

“And he’ll tell you himself that he nearly fell to the floor,” his wife Rebecca said.

The designs show 43 Accessory Dwelling Units, or ADUs planned for a yard smaller than half a football field. That’s more homes than the rest of the street combined.

Batista’s neighbors, Eric and Lisa Becerra, helped spread the word to neighbors.

“They’re like, ‘No, we’re not zoned for that,’” Eric Becerra said. “And then I’ll send them the plans, and they’re like, ‘Oh my god.’”

“They had no idea how this could happen without public notice, without a public hearing, without it adhering to a community plan, without following the planning process,” Lisa Becerra said.

That’s by design.

The ‘infinite housing glitch’

ADU developers are not required to do any of that. It’s part of what makes ADUs cheaper and faster to build — about $250 per square foot compared to $700 per square foot for a typical single-family home, one report found.

California hopes lower fees and less regulations will entice developers to build more housing that’s not high-rise apartments or single-family homes, but something called “the missing middle,” which proponents think is desperately needed to meet California’s housing shortage.

The state allows one ADU and a smaller, junior ADU on each lot. They’re commonly called “granny flats” or “casitas.”

In 2019, the state legislature required cities to develop strategies to create ADUs for households with low incomes.

In response, San Diego passed legislation allowing two more ADUs, as long as one of them is priced affordably. And, if your lot is within a walking mile of a major public transit stop — existing or planned — there’s no limit.

Nolan Gray, the Senior Director of Legislation and Research for California YIMBY, named it an “infinite housing glitch,” though the projects do still have to follow existing regulations for square footage and height requirements, so it’s more “as much as you can fit.”

That has resulted in some proposed projects with more than 100 units on a single lot, which critics call “granny towers.”

Those are rare. The typical Bonus ADU project is about four units.

Mayor Todd Gloria called it “gentle density,” pointing to a project with four new one-bedroom units and a garage studio.

But many of the largest projects in the pipeline are in the Encanto area.

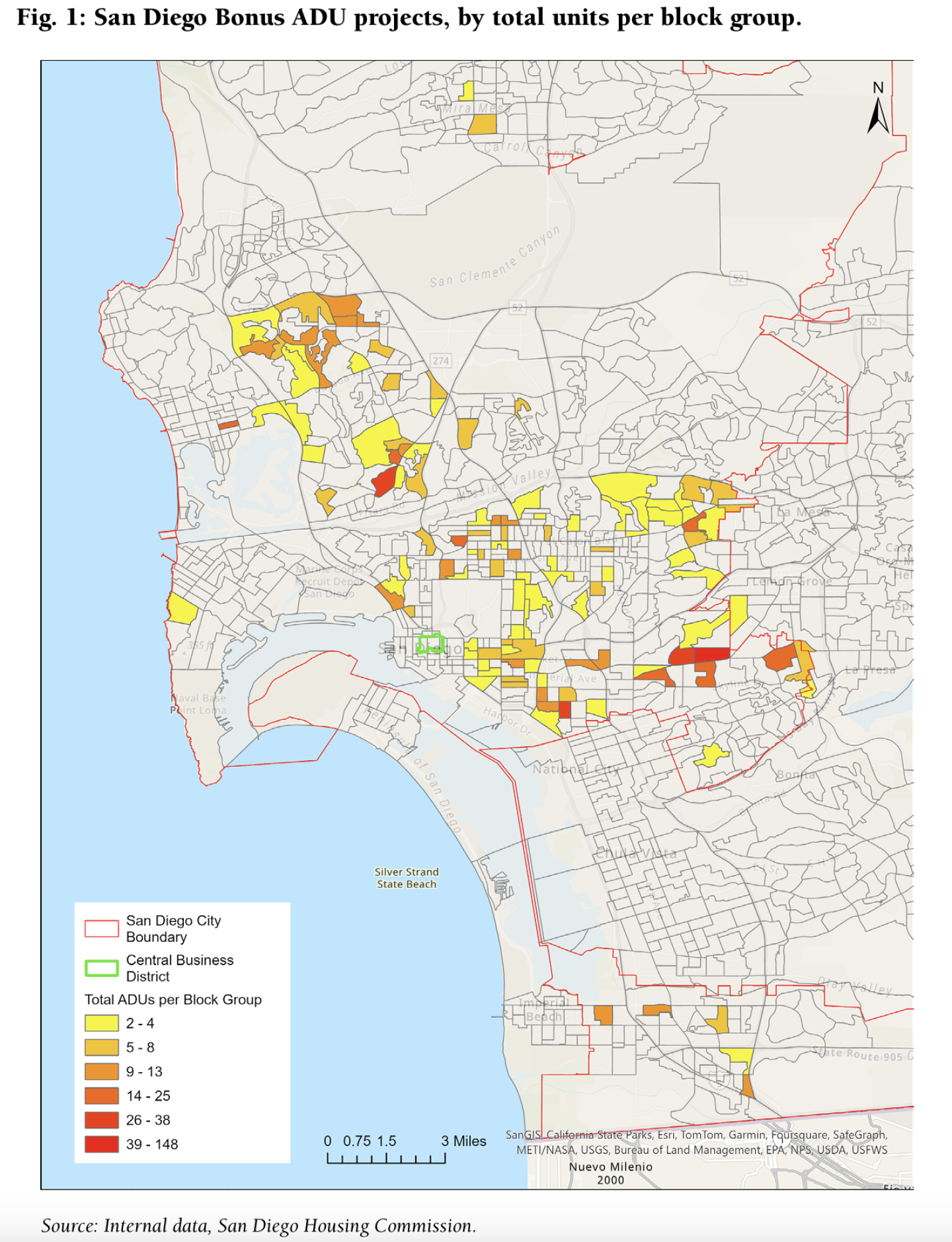

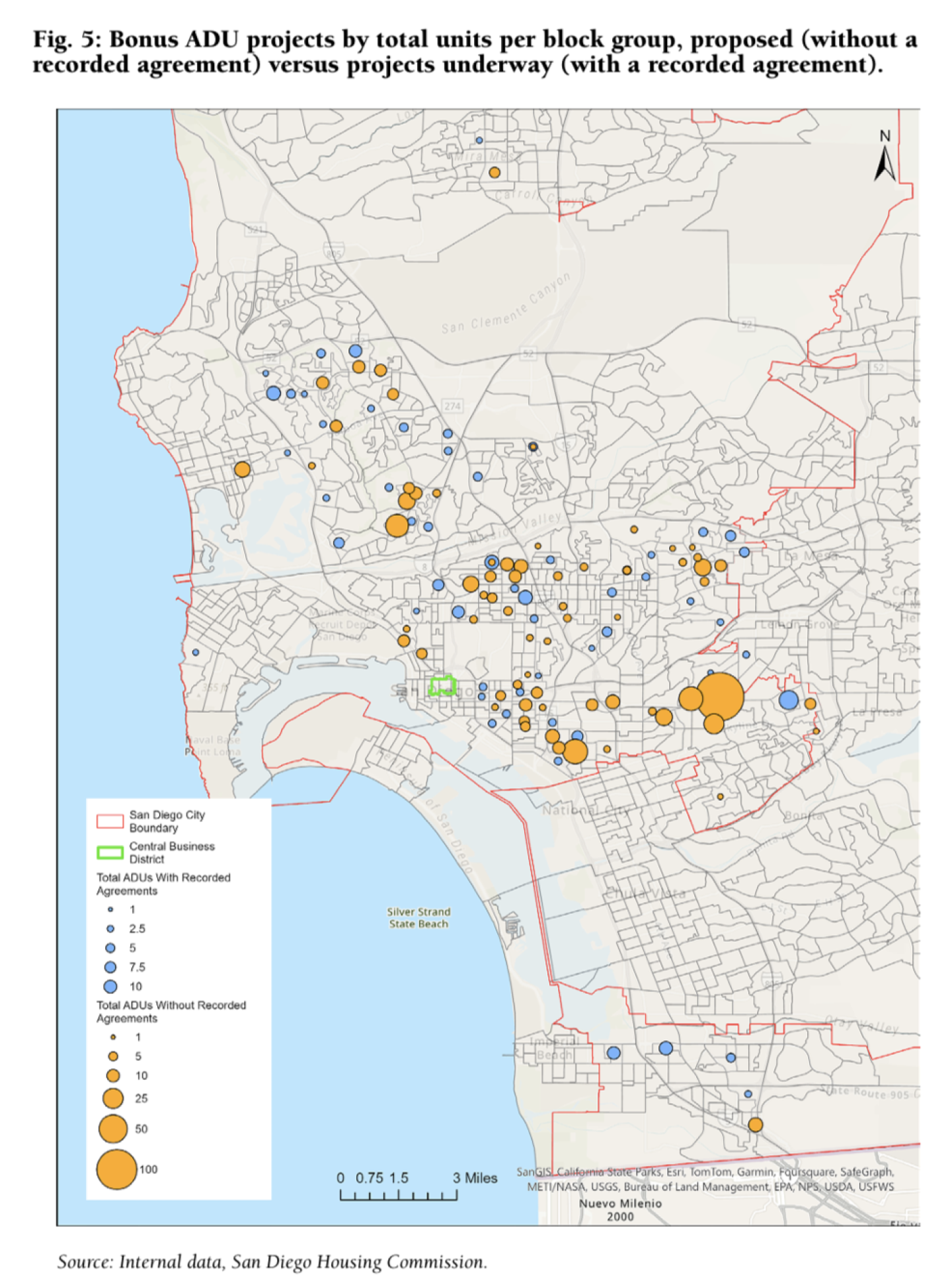

Editor's note: The maps below are from a mid-2024 assessment of San Diego's Bonus ADU program. Researchers from UC Berkeley and University of Texas at Austin constructed these maps using internal data from the San Diego Housing Commission, some of which may not be included in publicly published data. This includes projects that, at the time, were proposed by developers but not yet approved by the city. Some projects may have been discontinued in the months since, and other projects may have been added.

“We started peeling the onion to realize that it wasn’t just this lot next to ours, but upwards of 10 to 12 properties that we know about that are using the same bonus ADU loophole,” Rebecca Batista said.

In 2020, the state gave San Diego a goal of building more than 100,000 new housing units before 2030. More than half of those are supposed to be affordable.

The Bonus ADU program is helping the city deliver on that goal. Almost 2,000 ADUs were permitted in 2023.

As of July, all the units designated as affordable were priced above the area’s median income, targeting moderate income-earners rather than low-income earners.

A spokesperson for the city responded to questions by email.

“Prior to the creation of the ADU Home Density Bonus Program, affordable ADUs were rare in San Diego,” Peter Kelly said.

Kelly didn’t directly address questions about neighbors’ concerns that the program exceeds the densities prescribed in the Encanto area’s community plan, but did say updating community plans would help meet housing goals, and welcomed feedback from the community.

He also pointed to new homes being built in high resource neighborhoods.

About 30% of affordable ADUs have been permitted in high resource areas, Kelly said. The most homes approved between 2021 and 2023 were in the College Area, Clairemont Mesa, Uptown and North Park.

Encanto-area neighborhoods make up less than 4% of the Bonus ADUs already permitted, he said.

But the scale of individual ADU projects coming down the pipeline for Encanto are much larger, something researchers from UC Berkeley and the University of Texas at Austin noted in their early assessment of the program.

“An additional pattern the city should monitor is where large-scale Bonus ADU projects are being proposed by for-profit developers,” they wrote, noting one proposed project at the time that would put 148 units on one Encanto lot.

“Although income-restricted units may provide stability to renters in lower-income neighborhoods, the city may not want to see such a high concentration of units in areas that have historically absorbed more than their fair share of housing development,” the report titled, “Not So Gentle Density: An Early Assessment of the San Diego Bonus ADU Program,” found.

Co-author Jake Wegmann doesn’t think that concern should stop the program.

“It's just more something for the city to pay attention to rather than something that we saw as this three-alarm fire that the city needs to act on immediately,” he said.

He called the Bonus ADU program one of the most significant housing reforms in the entire country.

He said there might also be reasons why the city does want such large-scale ADU projects in low-income neighborhoods like Encanto: “It’s a tight housing market in a neighborhood like Encanto. There are a lot of people that need relief, and building more housing there might provide some relief.”

But he noted a historic pattern of looser zoning in lower-income neighborhoods that make it easier to build there, leading to residents feeling “besieged by development” while not seeing the same in wealthier neighborhoods like La Jolla.

The chicken, the egg and the neighbors waiting decades for it to hatch

Encanto makes sense for developers. It has larger lot sizes for less money than elsewhere in the city.

The neighborhood used to be redlined. Today, neighbors are mostly Black and Latino and low-income.

Batista isn’t opposed to more housing. Say, six more homes on the lot next to her.

But 43 more has her worried.

“We have very little help out here and very poor infrastructure. And I would say we are more than happy to have more housing here if it's done in the right and the responsible way,” she said.

Under state law, ADU developers don’t have to provide parking.

Standing on Tarbox Street, it’s hard to imagine where more cars would go.

The road isn’t maintained by the city; it’s up to residents. It’s riddled with potholes and cracks. There are no sidewalks or storm drains. There are only two street lights. Overgrown trees and parked cars jut into the road. Often, there is room for just one car to pass.

“How are they going to feed the need of those people when they can't even feed the need of the community?” Eric Becerra asked, gesturing at the empty lot that would soon house 44 new neighbors.

Like many of his neighbors, Becerra’s a lifelong Encanto resident. He grew up off Euclid Avenue during an era with higher gang violence and news coverage that fueled prejudices and fear. He bought this home 20 years ago and raised his children here. With his neighbors, he worked to turn the community into something they were all proud of, in spite of historical disinvestment by the city.

California ADU developers don’t have to pay impact fees or conduct environmental reviews.

Kelly acknowledged concerns about the City waiving impact fees and parking requirements, which state law mandates they do.

“These are challenges that the City is aware of and is committed to addressing through state legislation or future local regulatory action,” he said.

The city designated Encanto as a neighborhood that is disproportionately affected by environmental burdens and health risks.

It’s also in a zone that’s at a high risk for fires. Unlike apartments, ADUs don’t have to have sprinklers.

The neighborhood flooded last January. More concrete instead of grassy lots means more water runoff.

Wegmann calls the infrastructure problem a chicken-and-egg dynamic.

“People will say, ‘Well, we shouldn't build any more housing in this area because the infrastructure can't handle it. Then on the other hand, sometimes you hear, “Well, why would we add infrastructure to this neighborhood? Because there aren't enough people there to justify it,’” he said. “I'm not saying that those concerns aren't ever valid. I'm just saying that both of those arguments, if you take them to their logical conclusion, you talk yourself into never building anything.”

Lisa Becerra wonders what Encanto neighbors, present and future, are supposed to do while they wait for infrastructure investment to catch up.

Neighbors have begun to organize. About 50 of them meet for potlucks and wore bright yellow shirts to the mayor’s state of the city address. They created a petition that in just two weeks has more than 500 signatures. Eric Becerra said they would consider legal action, if that’s what it takes to stop this development from being built.

“This has turned us into activists, and it’s been really beautiful bringing our community together for something we all believe in. We know how special Encanto is,” Rebecca Batista said.

Two weeks after they discovered the plans for the lot next door, the Batistas started walking with their two young children to the closest major public transit stop.

It’s supposed to be a mile away at most to designate the lot next door as a “sustainable development area” and grant developers rights to build unlimited ADUs there, but Google Maps says it’s 1.1 miles.

With no sidewalk, they are forced to walk in the road. Cars and trucks rattle by. The wheels of their double stroller and their daughter’s scooter bump hard over potholes.

They pass a smaller bus stop with no shade. Neighbors set their own chairs on the grassy incline.

One empty wooden chair, black paint peeling, belongs to an long-time neighbor.

Batista said the woman just sold her property to a developer.

Council to debate

In a twist not planned on the public agenda, the San Diego City Council voted Tuesday to debate San Diego’s Bonus ADU Program.

The motion was raised by District 4 Councilmember Henry Foster III, who has advocated repeatedly for increased housing density but says this program is causing damage.

“The current ADU Density Bonus program as implemented is destroying community character, impacting for-sale opportunities, and creating unsafe conditions. We must pause this program and address all unintended consequences and negative impacts that are affecting communities citywide,” he said.

Other councilmembers said similar concerns have been raised in their districts.

They directed city staff to return to council within 60 days with an action item to remove the program.

It was bundled with a motion to repeal a controversial footnote of city code, and Foster declined to separate the two motions. The motion passed unanimously, with District 9 Councilmember Sean Elo-Rivera absent.