Editor's note: This story contains graphic descriptions of violence.

It started as a simple call to San Diego police about three young people being drunk in public. It ended with one young man bleeding from his face after being smashed into a police vehicle, and another wedged between seats in the back of a police car, covered in pepper spray.

“Why are you choking me?” one of the men called out to the officer during the encounter outside the San Carlos Recreation Center on a Sunday morning in August 2017. Both young men appear to be people of color in police body camera videos, while the officer, Timothy Romberger, is white.

Police Internal Affairs investigators found Romberger violated policy by using excessive force five times during the arrest and refusing to offer the suspect medical care.

But the public will never know what discipline Romberger received — if he received any at all. That’s because the disciplinary actions are missing from his file, and San Diego Police officials refuse to provide a specific explanation as to why.

One thing is clear: Romberger wasn’t fired over the incident. He went on to face two additional Internal Affairs investigations in the next two years. Then in 2019, he was fired after he held a gun to his fiancé’s head. He pled guilty to felony assault and was sentenced to six months in jail.

Missing discipline files

Romberger’s case was one of 93 reports of misconduct among San Diego police officers that were recently disclosed under California transparency laws. But almost one-third of those cases don’t include information on any disciplinary action against the officers.

Out of the total 93 cases, a third are for officers causing physical harm to citizens, with excessive force ranging from punching to hitting with a flashlight to using carotid restraints for too long. Six of those excessive force cases are missing disciplinary records, including:

- An officer who pressed his elbow into a suspect's head for 40 seconds and failed to document it

- An officer who released a police dog on a man with his hands in the air

- An officer who hit a man with a flashlight who was running away, then shoved him after he was in handcuffed

A quarter of the total cases are for discrimination, with officers making racist, homophobic or sexually suggestive comments to members of the public and other sworn personnel. Half of those cases are lacking disciplinary records, including:

- An officer who used a racial slur while saying he killed Black people for a living

- An officer who had sexual photos of women in his cubicle and sent an email using a homophobic slur

- An officer who told a prisoner to "walk to the back of the bus like Rosa Parks"

The findings concern advocates and attorneys, who have pushed for more transparency among California’s police agencies.

“Law enforcement officers possess the most extreme power possible,” said David Loy, legal director at the First Amendment Coalition. “They have the power to arrest, to detain, to use force, and ultimately to kill if deemed legally necessary. The public, the press, researchers, scholars, everyone has a compelling interest in transparency and accountability as to how police powers are used.”

Misconduct records

Despite the missing records, the San Diego Police Department’s case files offer the public some insights into how its nearly 2,000-person force is held accountable.

In the 63 misconduct cases where disciplinary records are available, more than half resulted in reprimands, the lowest “official discipline” an officer can receive. These written letters are supposed to remain in personnel files for employees’ entire careers in the department, according to San Diego Police Capt. Jeff Jordon, and can affect promotions and commendations.

Suspensions occurred in one-quarter of the cases, the records show, and officers were terminated three times.

SB 16, which went into effect last year, requires California police agencies to publish records on several categories of misconduct, including discrimination, excessive force and unlawful searches and arrests. It builds on another law from 2018, SB 1421, which publicized findings of dishonesty and sexual assault among police officers, in addition to records of officers shooting people and using force resulting in great bodily injury.

But SB 16 only covers cases where findings were sustained — if Internal Affairs exonerates an officer, the records don’t have to be disclosed. And the cases that are now public often lack the discipline doled out to the wrongdoers.

“California's opened the door on transparency and that's a good thing,” Loy said. “But it still has a long way to go.”

San Diego Police’s explanation

San Diego Police Capt. Jeff Jordon, who oversees police records, refused to do an interview for this story but answered questions by email. He said the department is disclosing all records available in the misconduct cases and complying with transparency laws.

Jordon said records on disciplinary action could be missing for several reasons — one being that the officer didn’t receive formal discipline, but instead, an informal consequence like a verbal warning that may not stay in the officer’s employment files. It’s also possible the officer left the force before discipline was issued.

A spokesperson for Mayor Todd Gloria also declined to comment on these issues.

Retired La Mesa Police Captain Dan Willis is an expert on police culture and psychology, and he said for many cases, it’s likely the punishment was not severe.

“The most reasonable explanation is it was less than formal,” he said. “Maybe the guy had to take a class, maybe he had to do some different training. Maybe he just got scolded by the lieutenant.”

Another explanation Jordon gave is that officers’ disciplinary files are purged three years after they leave the force. However, that doesn’t explain about half the records — about 15 of the cases without discipline information are for officers still on the force.

For cases where officers did leave the force, the full investigative file from Internal Affairs remains, but the consequences for the officers don’t.

The San Diego Police Department refused to clarify why disciplinary action was lacking from specific case files, citing the Peace Officer Bill of Rights, which gives protections to California police officers.

Other missing material

Romberger’s use of excessive force started when he approached one of the young men outside the San Carlos Recreation Center. The man turned around and punched Romberger in the arm, according to the Internal Affairs investigation.

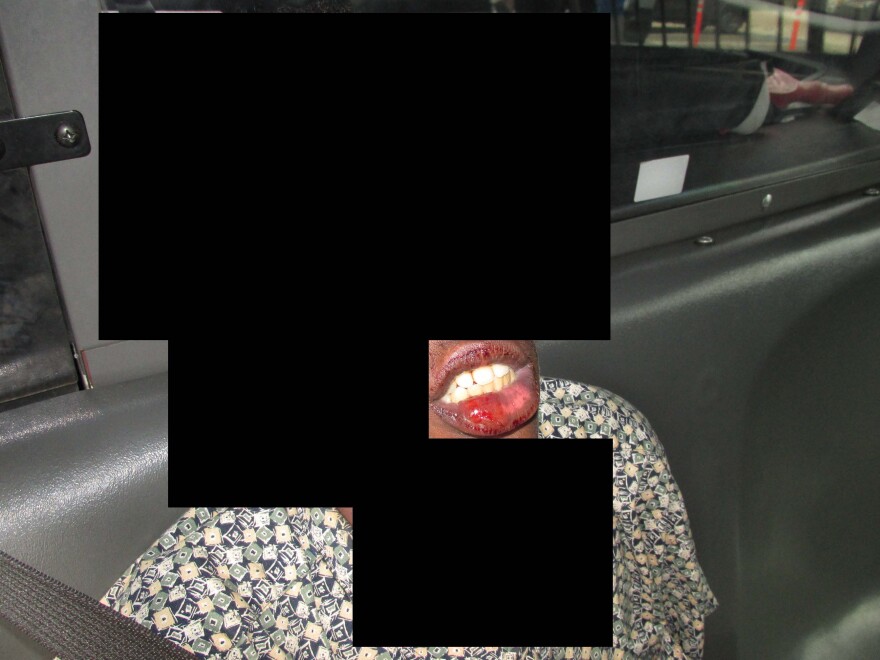

Romberger handcuffed the young man, then body slammed him into a patrol car, splitting his lip open. That’s when the young man asked why he was being choked.

Moments later, Romberger grabbed another young man by the neck and pulled him out of the vehicle, putting a hand at the base of his throat. Investigators concluded that the suspect — who was around 20 years old — was not resisting or an immediate threat at the time.

When one of the young men was sitting in the police car, Romberger pepper sprayed him in the eyes from a distance of 12 to 18 inches away, according to the report and police body camera video. He also didn’t seatbelt the man, causing him to fall down between the seats when Romberger drove him to jail.

Romberger also didn’t flush the suspect’s eyes out with water after pepper spraying him, as department policy requires, and failed to properly document the force he used, according to police records.

Investigators said Romberger’s actions “potentially opened the department to civil liability and reflected discredit upon the members of the Department.”

Romberger told Internal Affairs that he was trying to protect himself during the encounter, but he acknowledged his conduct did not follow policy in several instances. He could not be reached for comment for this story.

His attorney told police investigators that Romberger had been “going through a turbulent personal situation with his wife and mother of his child,” which may have contributed to his state of mind at the time.

In the case file, the public can read the details of the altercation at the recreation center, and Romberger’s interview with Internal Affairs. But the original recording of the interview, which is supposed to be disclosed to the public, is missing. Jordon with the police department said he didn’t know why.

Court records show Internal Affairs investigated Romberger again the following year when he was suspected of domestic battery, and once again when he was suspected of vandalism against his partner. The records don’t state whether the allegations against Romberger in these cases were sustained.

The documents state Romberger received a 30-day suspension and was transferred to the telephone reporting unit for 13 months because of an Internal Affairs investigation. It’s unclear which incident landed Romberger with those consequences.

The discipline was only made public because of the criminal prosecution against Romberger in 2019, not because of records published by the police.

‘It’s important to know’

Sharmaine Moseley, the interim executive director at the city’s Commission on Police Practices, said the public has an interest in knowing the discipline officers like Romberger received.

“I think we would expect something more in the file,” Moseley said.

“It's important to know, especially in a case like this that's so serious,” she added.

Moseley said the police misconduct files she’s reviewed usually only have one or two allegations of excessive force in them, so having many in one file, as in Romberger’s case, is unusual.

Willis, formerly of the La Mesa Police Department, reviewed the records and believes the Internal Affairs investigators were rigorous in their work.

“This was an extremely thorough investigation,” he said. “They basically left no stone unturned.”

Willis said he supports efforts like SB 16, because they increase the public’s trust in policing.

“If we can show the public that we're doing everything we can to hold our people accountable, then that's how we're going to start building the bridges,” he said.

Part two of this series will look at officers with missing disciplinary records who have been rehired by different local law enforcement agencies. Read it here.