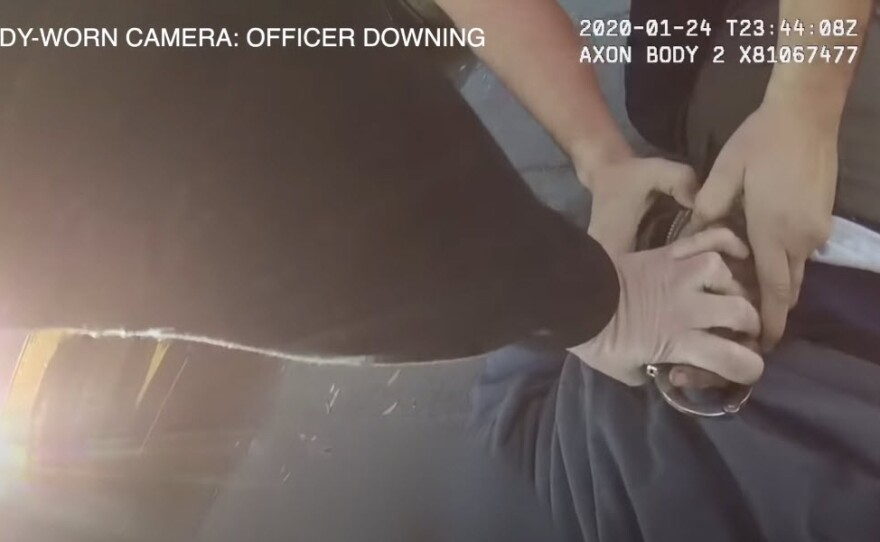

In January 2020, two San Diego Police Department officers saw 31-year-old Toby Diller walking on 54th Street in Oak Park with an open container. They pulled their SUV over and Diller started running away.

The officers jumped out of the SUV and chased him, yelling “Stop, stop!” They tackled him and then one of the officers shouted that Diller had grabbed his gun. Officer Devion Johnson shot Diller in the head, killing him instantly.

Johnson’s approach and steps leading up to the shooting almost certainly would go against the teachings in a de-escalation training program that had started the year before. The eight-hour training course teaches officers to slow down, assess the scene before taking drastic action and communicate clearly with suspects.

But Johnson never took the course before leaving the force in September 2020, according to records from the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training. In March 2019, San Diego County District Attorney Summer Stephan rolled out an eight-hour de-escalation training program for local law enforcement agencies, but it took a year to train the bulk of local police officers.

RELATED: Search the police records database

Stephan did not require departments in the county to send their officers to her training. Yet, as of this month, more than 3,000 officers across 19 departments have completed it, according to the DA’s office. The glaring exception is the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department. None of the department’s 2,600 sworn deputies have taken the DA’s training.

Instead, Sheriff’s deputies completed four hours of de-escalation training in 2019, plus watched a follow-up video that is 14 minutes long. The department also updated its existing eight-hour training courses on strategic communication and de-escalation, which law enforcement deputies are required to take. So far, about 60% of the required deputies have finished the updated course, and the remaining will be done by March 2022, according to the department.

Stephan’s office said that updated training shares the same curriculum as her de-escalation course, but she wouldn’t answer directly whether she thought Sheriff’s deputies should have already taken her training.

“I'll judge what the Sheriff's Department is doing by the same standard I'm judging our training, so either way, so long as the training is given in the proper way in its format, then it's satisfactory,” she said.

'Slow down'

The DA’s training goes over concepts that advocate patience when appropriate, and for officers to not put themselves in vulnerable situations where they might have to shoot.

“So slow down, assess the situation, are there weapons involved and what are your capabilities that can de-escalate?” Stephan said. “We know not everything can be slowed down because you are dealing with an immediate, imminent threat. What we're talking about is the things that I see on body one camera where you can see that things could be slowed down.”

RELATED: Records reveal differences in how officers and suspects are treated after police shootings

Speaker 1: (00:00)

Two years ago, San Diego county district attorney summer Stephan introduced a new training program aimed at reducing police shootings, countywide K PBS investigative reporter. Claire trier says while some departments have trained more of their officers than others, there is hope it has sparked the beginning of a culture change. Morning. This story contains graphic descriptions and sounds

Speaker 2: (00:26)

In January, 2022, San Diego police officers saw Toby Dier walking in Oak park with an open container. When they pulled their SUV over, Dier started running away. The officers jumped out of the SUV and chased him, him yelling, stop, stop. They caught up to him and tackled him, put your hands behind your back. Then one of the officers shouted, he's got my gun, shoot him, officer Debbie and Johnson then shot Diller in the head, killing him instantly Johnson's approach and steps. Leading up to the shooting almost certainly would go against the teachings in a countywide deescalation training program that had started the year before district attorney summer Stephan created the training.

Speaker 3: (01:09)

So slow down, assess the situation, identify are there weapons involved? And, um, what are your capabilities that can deescalate?

Speaker 2: (01:20)

She says the eight hour training course teaches officers to avoid situations that lead to shootings. We

Speaker 3: (01:27)

Know not everything can be slowed down because you are dealing with an immediate imminent threat. What we're talking about is the things that I see on body worn camera, where you can see that things could be, be slowed down.

Speaker 2: (01:43)

It's too soon to tell whether any of the training is having an impact on the number of officers, countywide who shoot suspects. But Stephan says in

Speaker 3: (01:52)

Cases where an individual is not armed, um, or is not armed in a way that is gonna cause serious Bodi injury, um, that, that, you know, just their behavior is of concern. Seeing a different interaction and less lethal force used. That would be a win

Speaker 2: (02:15)

As of this month, more than 3000 officers across 19 departments have taken the course, the glaring exception, the Sandy O county Sheriff's department, none of the departments, 2,600 sworn deputies have taken the DA's training. Instead Sheriff's deputies completed a separate training that is just 14 minutes and 28 seconds long. The department has also updated its existing eight hour training courses on strategic community and deescalation, but so far just 750 deputies have been through that training. Travis Norton, a use of force expert and trainer says the length and intensity of the training matter. A short video is not gonna

Speaker 4: (03:00)

Give you what an eight hour day where you're interacting with an instructor. You're doing decision making exercise. You're actually having to work through problems that you could encounter out in the field to help again, create that, that artificial

Speaker 2: (03:11)

Experience. Sheriff's department officials wouldn't agree to an interview for this story. This is a far cry from the situation up the coast in Berkeley, where the police department has been offering eight hours of hands on deescalation training since 2016, Berkeley police Lieutenant Joe Oakies helped design it.

Speaker 5: (03:30)

You know, we incorporate that training. As I mentioned in, into really all of our use of force training. There's a component of it. And including as I said, the, the most recent training that we did. So, so it's reinforced there.

Speaker 2: (03:44)

The hope is deescalation training would become like body worn cameras, which officers resisted at first, but now embrace because of the accountability it brings to their jobs. So says Darwin Fishman, a leader of racial justice coalition, Diego. It actually strengthens

Speaker 6: (04:01)

The police force. It strengthens the community police relationships. It really has a better impact on crime and it creates a more healthy

Speaker 2: (04:08)

Communities. He and other activists say these small steps are important, but a far larger driver of change comes from the community.

Speaker 1: (04:19)

Joining me as Cape PBS, investigative reporter, Claire Traeger, and Claire. Welcome.

Speaker 2: (04:24)

Thank you.

Speaker 1: (04:25)

Now you've said that San Diego district attorney summer Stephan created the deescalation training being used by police departments, countywide isn't there some national deescalation program that police forces can use. I mean, does each county have to come up with its own well

Speaker 2: (04:42)

You're right. That there is, um, a state level system of training, not just for deescalation, but for all, uh, police procedures and local departments have to abide by standards that come from that statewide training. Um, and so the, the deescalation training that she designed is based those standards and, you know, satisfies all of, all of the requirements they have, but then yeah, you know, each region can amend and, and come up with their own probably to meet the specific, uh, needs of their region or be more catered towards the, the populations that they're working with. So

Speaker 1: (05:19)

Let's go through the incident that you describe at the beginning of your report, how would deescalation training possibly have changed the outcome? For instance, I was wondering, would deescalation stop police from chasing someone just for carrying an open container? Yeah,

Speaker 2: (05:36)

You're right. I think that's the biggest thing that, that the training is going to, or is emphasizing, which is, is when an officer makes that very initial encounter with someone they as summer Stephan said in the story, slow down and assess the situation and then approach someone in maybe a way that's not going to set off alarm bells for that person. So if you pull over your car, you maybe get out slowly, you don't jump out of the car or you keep a safe distance things that if someone is maybe under the influence or having mental health issues, isn't going to, to set them off. And then once the, the man in that, I started the story with started running away, the officers start chasing him. And I think that there's now more, uh, focus on in those situations, you know, what should an officer do if that person isn't a risk, do they need to chase that person? Or can they just let that person go? Which, um, I've covered in, in previous stories. I think then once they are in the situation where they've tackled him and he has been able to UN holster one of the officer's guns and is holding a gun at that point, yes. You know, lethal use of force is still acceptable because the officer's lives are at risk. And when, uh, the district deter and he reviewed this particular shooting, she found that the use of force was justified.

Speaker 1: (07:03)

Now you say, it's too soon to tell if the deescalation training is working, how would its effectiveness be assessed?

Speaker 2: (07:10)

Right. Well, so, um, as I said, in the story, officers are, are taking it and now pretty much every officer in the county has taken the training. So I think what summer Stephan said is that she's looking to see the number of violent confrontations between citizens and police go down, especially shootings.

Speaker 1: (07:30)

And are the departments keeping track of whether their officers are using the new deescalation methods? Well,

Speaker 2: (07:36)

The, the other thing that goes with this is some departments have now changed their policy to say that deescalation must be used. Of course, they still write in all of this language, conditional language, but there, that is a change in the policy from, I think it was, should be used before to must be used. And so then, yeah, departments will be assessing when there are, these encounters was deescalation used, could it have been used. And so I imagine that they would be keeping, keeping track of that. You know, if they're gonna enter it all into one central database, I don't know, but these interactions will be evaluated with those standards in mind.

Speaker 1: (08:14)

Now it's my understanding that the San Diego Sheriff's department did not want to be interviewed about the new deescalation training. Did they tell you why?

Speaker 2: (08:23)

Yeah. I mean, the, the Sheriff's department now has had this, um, response to multiple requests for me, where they just say that the people who are in charge of that area are too busy. um, you know, and I give them months to, to do an interview and they don't want to do an interview. And so, you know, I, I don't know why I really wish it, it makes it so much easier to be able to talk with the officials who are in charge of whatever it is that the story is about to provide their explanations. But that seems to be just a common trend among, uh, local law enforcement, which is disappointing

Speaker 1: (09:01)

Considering how apparently guarded the Sheriff's department is about discussing this training. Is there a sense that police departments are not yet exactly on board with the deescalation concept? Well,

Speaker 2: (09:13)

Yeah, that is gonna be the real test is, you know, this is coming from the top with this high level. Okay. Everyone has to do this training. The question is how will the training really be rolled out? Will it be presented in a way that that officers are, are going to be amenable to, um, and you know, not say, okay, this is just one more thing that we have to do. What a joke. I think in, in Berkeley, I had done stories, uh, last year about how their deescalation training works and the officer or the Lieutenant who is in charge of presenting that training described how he talked to officers about it saying, have you ever been in a situation where you could have been justified to shoot and you didn't, and most officers have stories like that where they potentially could have shot someone, but they didn't. And he said, okay, that's deescalation. So start from there. So presenting it in a way of officers, knowing that they are capable of, and, you know, already have those tactics down and teaching them about it from that frame of reference.

Speaker 1: (10:21)

I've been speaking with KPBS, investigative reporter, Claire trier, Claire. Thank you. Thank you.

The training also covers implicit bias, how to recognize and respond to people in delirium due to substances, and involves simulations and role-play scenarios.

It’s too soon to tell whether any of the training is having an impact on the number of officers countywide who shoot suspects. But Stephan said she’s heard positive feedback from officers and is hopeful that she will soon see fewer officer shootings in cases where the suspect is not armed with a gun.

“In cases where the individual is not armed or is not armed in a way that is going to cause serious bodily injury if we are seeing a different interaction and less lethal force used, that would be a win,” she said.

Travis Norton, a use-of-force expert and trainer, said the length and intensity of the training matters.

A short video “is not going to give you what an eight-hour day, where you're interacting with an instructor, you're doing decision-making exercises, you're actually having to work through problems that you could encounter out in the field to help create that artificial experience,” he said.

A spokeswoman for the Sheriff’s Department wouldn’t make any officials available for an interview for this story. Instead, she answered questions by email, saying the updated training that deputies will now take includes “lecture, group discussion, and hands-on/practical strategic communications and de-escalation training.”

A new state law, SB 230, requires agencies to create de-escalation policies and asks every agency to train their officers on that policy. Stephan said her training far exceeds those requirements.

The Berkeley approach

Meanwhile, the Berkeley Police Department has been offering eight hours of hands-on de-escalation training since 2016.

“But beyond that, we incorporate de-escalation into all our use of force training, so it’s reinforced there,” said Berkeley police Lt. Joe Okies, who helped design the training. “We also participate in training that covers mental health crisis response, and our department is currently expanding the number of officers that have been through the state-certified 40-hour Crisis Intervention Training.”

RELATED: San Diego Police use force most often in neighborhoods south of Interstate 8

Okies said while Berkeley has a reputation for being a special place that is very progressive, this type of training can happen anywhere.

“We are a city like any other, a diverse city with a range of public safety challenges,” he said. “This type of training is something that many other agencies are successfully able to implement.”

The hope is that de-escalation training could become like body-worn cameras, which officers resisted at first but now embrace because of the accountability it brings to their jobs, said Darwin Fishman, a leader of Racial Justice Coalition of San Diego.

“It actually strengthens the police force, it strengthens the community-police relationships, it really has a better impact on crime, and it creates a more healthy community,” he said.

Some criminal justice reform activists say they are encouraged by what he’s heard from Stephan and others in local law enforcement regarding more accountability for how police use force. Khalid Alexander, the founder of the nonprofit advocacy organization Pillars of the Community, said those small steps could be the beginning of a very large culture shift.

“The conversation has changed, where people are beginning to talk about a disproportionate amount of money and the blank check that essentially goes to the police department,” Alexander said. “There's more media attention into incidents of police misconduct and really kind of questioning what the role of police is in our community.”

But, Alexander said, a far larger driver of change comes from the community.

“You have community members who are now beginning to question the authority of the police to be policing us in our neighborhoods, who are beginning to question what gives them the right to pull us over and harass us and prevent us from getting to work on time,” he said. “I think that we're only in the beginning stages in that movement towards holding police accountable, and it is only going to get larger and louder.