There is no easy way to count up all the money spent in San Diego County elections.

While candidates in a race have to file clear reports outlining all the money they’ve raised and spent, finding out the details of all the other groups throwing money into the election requires a lot more grunt work.

These groups, officially dubbed “independent expenditure committees,” can spend unlimited sums supporting or opposing candidates in an election, so long as they don’t coordinate with the candidates’ campaigns.

Often they spend more than the candidates themselves, who can only accept donations from individuals contributing up to $1,000 each per election cycle.

The special election for the county Board of Supervisors’ District 4 seat is no exception. The candidates have spent $185,000 combined on their campaigns, but outside groups have funneled another $900,000 into the race, according to an inewsource analysis of campaign finance data.

That money is being spent on mailers, television ads, lawn signs, surveys and more.

There’s more to come. The candidates and these outside groups have raised additional cash that they can deploy in the final weeks before Election Day on Aug. 15.

To compile the financial data, inewsource searched through reports on the Registrar of Voters’ campaign finance portal, downloaded all the data, combined it into one file and manually entered details about which candidates benefited from each transaction.

Thad Kousser, a political science professor at UC San Diego, says the high-dollar spending shown in inewsource’s analysis is a reflection of the race’s importance.

The Board of Supervisors oversees billions of dollars in public funds and key government functions in a county with more than 3 million residents. The winning candidate will replace former Supervisor Nathan Fletcher, who stepped down earlier this year following sexual assault allegations. Two Republicans and two Democrats on the board remain.

“The stakes are particularly high because it'll determine the balance of power between a board that is deadlocked right now,” Kousser said.

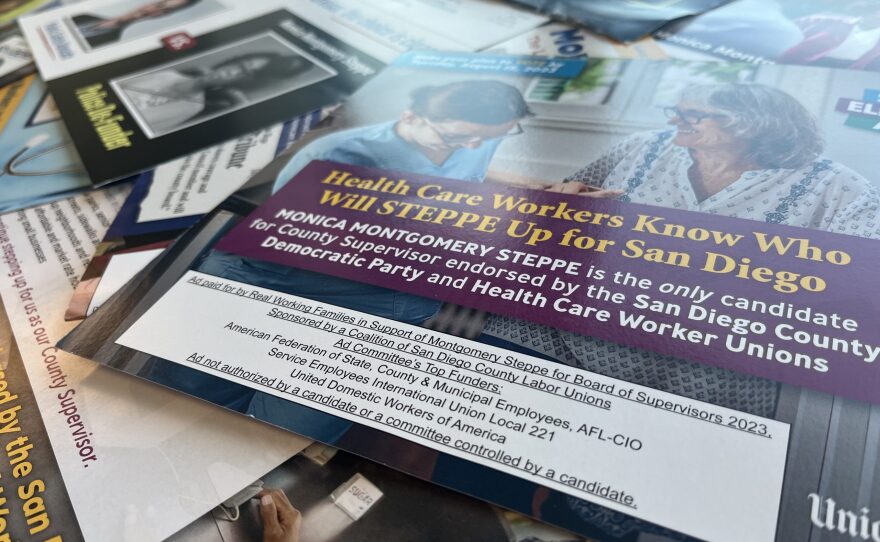

The data suggests one candidate as the focal point. Monica Montgomery Steppe, the current San Diego City Council president pro tem, has seen almost $400,000 spent in favor of her campaign so far, more than any other candidate.

Montgomery Steppe is also facing by far the most opposition spending — a total of $122,000, doled out primarily by law enforcement unions.

“The frontrunner almost always faces the harshest attacks,” Kousser said. “So I think this is a signal that she's the presumed frontrunner, and her opponents are trying to knock her down.”

Montgomery Steppe holds the endorsement of the local Democratic Party and conservation groups.

Another Democrat in the race, former U.S. Marine Corps Officer Janessa Goldbeck, was endorsed by the San Diego Deputy District Attorneys Association, which has spent $50,000 supporting her campaign.

Goldbeck, who is gay, has also gotten financial support from LGBTQ+ rights group Equality California, as well as a political committee funded by real estate groups.

Montgomery Steppe’s steep financial advantage comes from a coalition of labor unions. The group includes the American Federation of State, County & Municipal Employees along with SEIU Local 221 and United Domestic Workers of America.

Meanwhile, a local chapter of the Laborers International Union has chosen to spend $118,000 supporting candidate Amy Reichert, who is endorsed by the county Republican Party.

Ads supporting Reichert portray her as a candidate who will “protect our county” and “take our county back.” Mailers supporting Goldbeck frame her as a “public safety advocate” committed to “balancing protection and rights.” Those in favor of Montgomery Steppe boast her support from health care workers and working families, and they assert she is “ready to lead.”

On the other hand, attack ads from the San Diego Police union paint Montgomery Steppe as a “threat to public safety” and feature misleading and inaccurate statements about her police reform efforts, inewsource found.

Under state law, the candidates were not allowed to endorse or approve any of the messaging in the advertisements by outside groups.

Paul McQuigg, a fourth candidate in the race, has not faced support or opposition spending from outside groups.

In an interview, McQuigg said his friends and family are helping him run his grassroots campaign, which just crossed the $2,000 fundraising threshold that requires him to file financial reports with the state.

He questioned whether the independent groups supporting other candidates in the race were actually boosting their chances of victory.

“Just because a mailer goes out, that doesn’t mean that person’s gonna get votes from that because they don’t know how they’re going to perceive that message,” McQuigg said.

As for the other three candidates, they’ve each expressed concerns about the abundance of mailers and TV ads bombarding voters about their candidacy without their permission.

The ads are required to contain the names of the groups funding them due to state election laws, but the messaging can still appear to come from the candidates themselves if voters don’t examine the fine print.

The veracity of outside spending in elections was bolstered by a 2017 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Citizens United v. FEC, which found that independent groups have broad freedom to spend money supporting or opposing candidates for office.

Kousser said the ruling has hampered any meaningful reform.

“There's been a longstanding consensus that there's something wrong with the role of money in American politics,” he said, “but there's no consensus on how to fix it.”

First, we downloaded spreadsheet data from each group’s spending reports through the County Registrar of Voters’ campaign finance search tool. We used several search criteria for the upcoming special election to ensure as much data as possible was captured, since the reports can be uploaded to different parts of the search system. Then, we used an R script to compile all the data into a single file. We manually added data from additional campaign finance reports from PDFs that could not be downloaded.

By going back to the original spending reports, inewsource was able to code each expenditure as support or opposition for a specific candidate. This information was not available in the data downloads but was visible on the top of each spending document.

Lastly, we analyzed the data to look for trends and calculate totals.

The data was collected on Jul. 28, 2023. Fundraising and spending is expected to increase in the weeks prior to the election.