This November will be Martha Hernandez’s third time voting in an election since she became a U.S. citizen. Exercising that right is a priority for her. With a high-school aged son, she votes to advocate for neighborhood schools and improve her and her family’s quality of life.

But voting so far has been challenging. Her first time voting, no one at the polling place she visited spoke Spanish, her native and most comfortable language. She’s had questions while voting in the past, and having in-language assistance would have made a big difference in helping her feel confident in the process, she said.

“For me there is a total difference, from heaven to earth. Huge,” Hernandez said in Spanish.

As the local election office gears up for the November midterms, advocates for new American citizens say a lack of in-language voting materials and assistance at voting centers have made voting harder for communities who primarily speak minority languages.

Laws at the federal, state and local levels require county elections offices to provide in-language voting materials and oral language assistance for voters who speak those languages.

Data from the San Diego County Registrar of Voters shows more than 60,000 eligible voters – out of 1.9 million total in the county as of late September – requested voting materials in Spanish for the upcoming election. Nearly 2,000 requested materials in Filipino, more than 3,000 requested materials in Chinese and more than 7,000 in Vietnamese.

But actually hiring poll workers who speak languages other than English proves challenging each year, according to Cynthia Paes, San Diego County’s registrar of voters.

For the upcoming election, based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the county should hire 212 Spanish, 46 Filipino, 80 Vietnamese, 55 Chinese, 17 Arabic, 2 Japanese, 7 Korean, 6 Laotian, 4 Persian and 5 Somali speakers.

As of Oct. 26, the county has met or exceeded hiring goals for Spanish, Filipino, Arabic, Japanese and Korean poll workers, but that could be subject to change as some workers may drop out or fail to meet certain requirements.

Less than two weeks away Election Day and a day before selected vote centers open Saturday for early voting, the county has so far not met goals for Somali, Persian, Laotian, Vietnamese and Chinese poll workers, according to the registrar.

The registrar said they won’t have final numbers on the languages represented among poll workers and which locations they staff until after Election Day. For the first time, San Diego County will provide reference, or facsimile, ballots in Somali and Persian after a new policy from the Board of Supervisors mandated it. The votable ballot is only available in English, Chinese, Spanish, Filipino and Vietnamese, as required by federal law.

In-person translation services from bilingual poll workers at voting centers, however, could bridge the language gap. It’s one of the most effective forms of assistance for voters who primarily speak a language other than English, according to Maricruz Osorio, who co-authored a study on voting behaviors and awareness among first-time voters during the November 2020 elections.

That study found that in-person language assistance and help understanding the ballot was the biggest reason voters opted for in-person voting over voting by mail.

“What we find is that in-language message receiving is the most effective because they trust it,” Osorio said. “When you reach individuals in their primary language, the message doesn't get lost and they're more likely to trust sources from organizations that have worked with them before.”

Tele-interpretation, which allows someone to reach a live interpreter over the phone in any language, is available at all the county’s more than 200 vote centers. But having in-person bilingual poll workers changes the experience fundamentally for new citizens, according to Lilian Serrano, co-director of Universidad Popular, a Latino-serving nonprofit based in North County that provides social and educational support for immigrants.

“Their eyes light up. They feel like, ‘Okay, this is a place where I belong, a place where I can go to and once again exercise that right and responsibility of casting a ballot.”

Need for bilingual poll workers

Some election materials are provided in languages other than English, including the votable ballot, which is also available in Chinese, Filipino, Spanish and Vietnamese. But even for communities who get a reference ballot in another language, marking the votable ballot can be challenging.

And though the county elections office makes an effort to hire bilingual poll workers, they’re often not able to meet goals, which are set using census data. The goals are based on how many eligible voters in a precinct speak a shared language and are less than proficient in English.

Paes said that the county usually hires a sufficient number of Spanish and Filipino poll workers, but a few languages, in particular, are hard to hire.

“Generally, we always need Vietnamese speakers, Chinese speakers, any of the Asian languages, Somali, Arabic. It's always been really difficult.”

The Registrar of Voters recruits through targeted ads in bilingual newspapers, radio stations and social media. But even after getting prospective poll workers through the application and training process, they can’t guarantee who ends up showing up to vote centers on voting days, Paes said.

Because of that, the Registrar of Voters could not provide inewsource with a list of which polling stations would have in-person language assistance available.

A new state law signed by the governor in September will require county election officials to post online two weeks before Election Day a list of voting precincts that will have bilingual workers, but the law doesn’t take effect until next year.

Said Abiyow, founder of the Somali Bantu Association of America, said Somali language assistance is hard to find at polling locations in San Diego. He said he’s spoken with voters in his community who are hesitant about voting, knowing in-person language assistance may not be available.

The Somali Bantu Association supports Somali Bantu and other East African refugees in San Diego County, many located in City Heights. He said community members sometimes bring their ballots into his office for translation help, even when they receive a reference ballot in Somali.

“They don't speak any English. Their language is not there because (the county) say they provided Somali, but we have 84 languages in our office. We do translate them,” Abiyow said, adding that seeing a Somali-speaking person gives his community confidence in the voting process.

Tele-interpretation available, but not always helpful

In the absence of in-person translation assistance in their language, voters do have access to interpreting services over the telephone when they show up to cast their ballots.

But advocates for new citizens say accents and dialects can vary widely among speakers and tele-interpretation services don’t match the level offered by in-person language assistance.

“Actually having someone from San Diego makes a huge difference. And someone who knows the community who can answer questions that may come up,” Jeanine Erikat, policy associate with the Partnership for Advancement of New Americans, or PANA, in San Diego.

Resources for non-English voters

San Diego County provides election materials and resources for Spanish, Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese, Somali, Korean, Persian, Laotian and Arabic.

Through her work with PANA, Erikat has hosted listening sessions with new citizens from Somalia and Syria who are heading into their first time participating in an election.

“Folks were so excited that they could get to vote for the first time and were happy to know that there was a facsimile ballot,” Erikat said. “But there was a lot of concern and confusion on how do I transfer what I'm reading in the reference ballot into a votable ballot?”

More than the help bilingual poll workers from the community can provide with understanding the ballot, they also help new voters feel comfortable and welcome at voting locations, Erikat said.

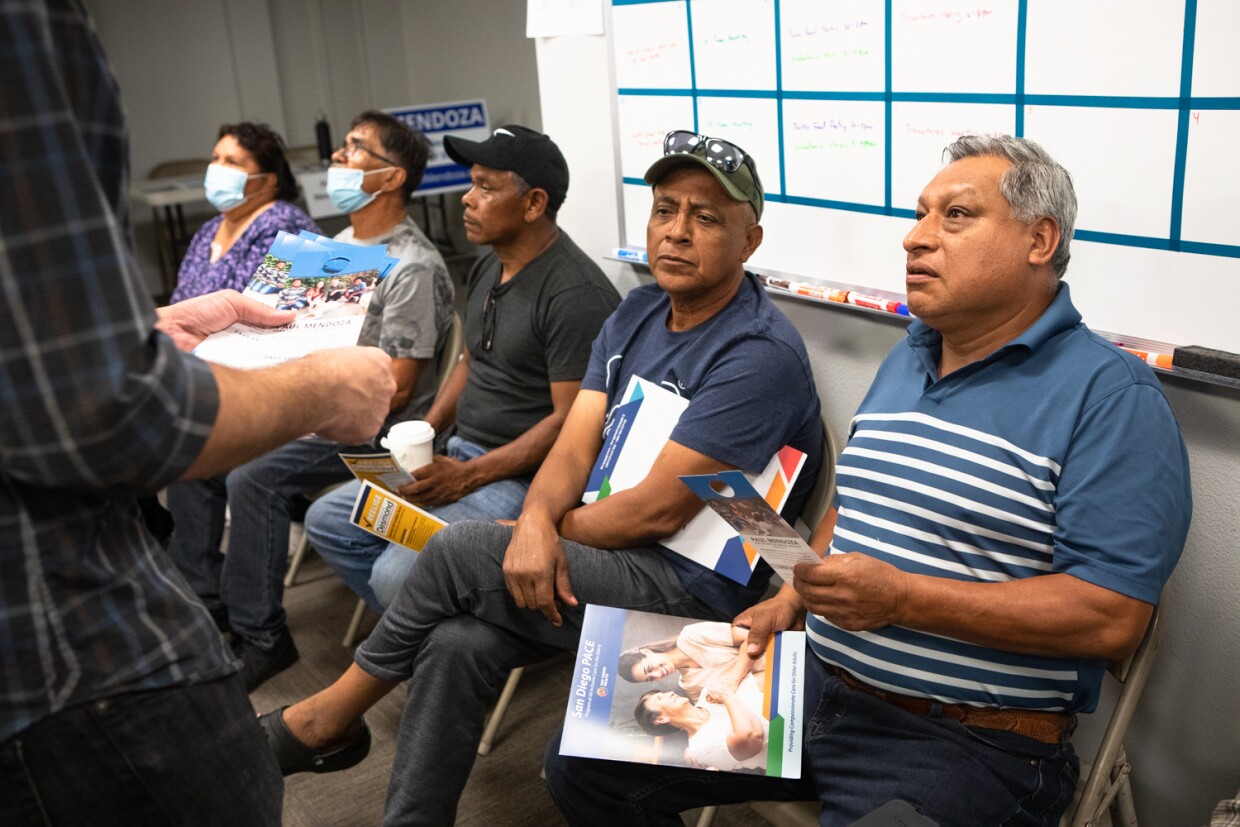

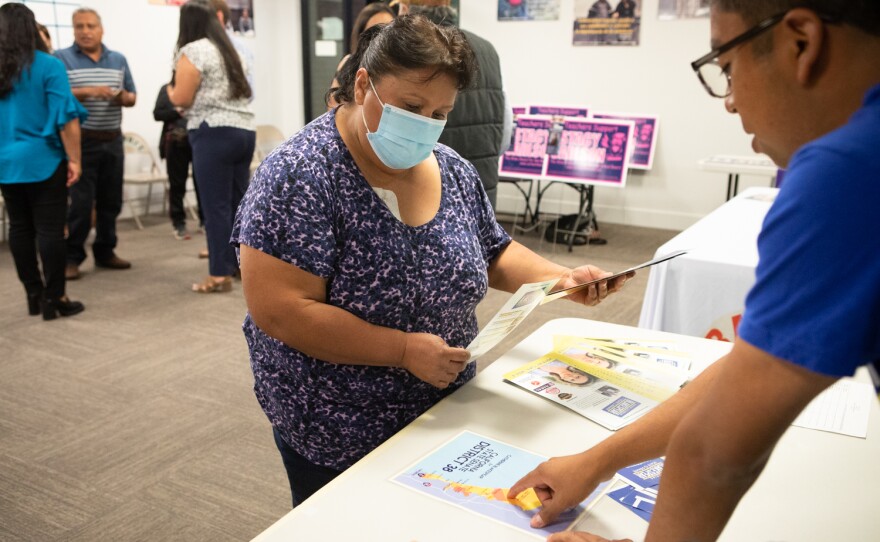

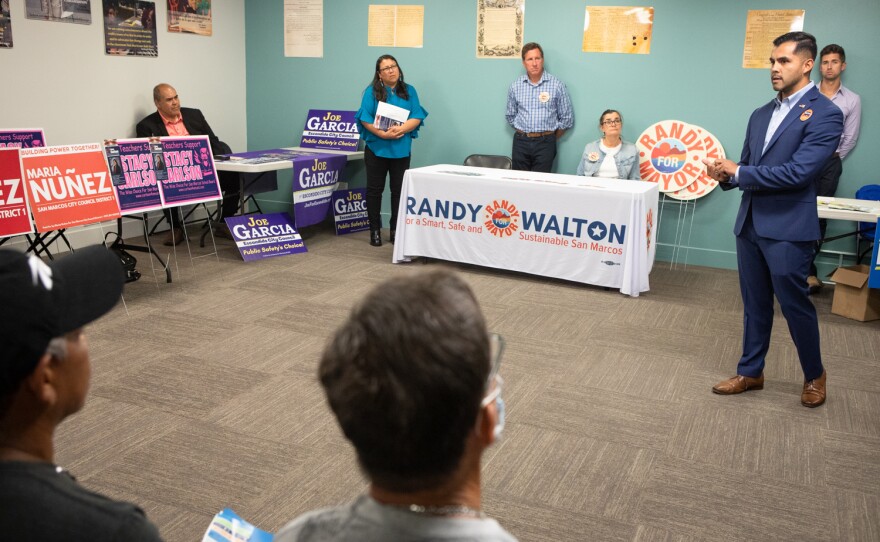

Nonprofits like PANA and Universidad Popular help to bridge the gap for new voters who face language barriers at the polls. In October, Universidad Popular hosted an elections fair in San Marcos dedicated to new voters in the community, and several brought their ballots with them to the event.

It was an opportunity for new voters including Ariam Diaz to hear campaign information from local candidates in her own language. Several local candidates, including for the local water district, school board and California State Senate, brought campaign materials and made a brief pitch in Spanish.

It’s Diaz’s second year voting since becoming a citizen, and she wants to vote for someone who will listen to the voices of Latinos in the community like herself.

“For me voting is important so that we are all heard,” Diaz said in Spanish. “My mother used to say, 'Grain by grain, person by person, we can be a majority group to make ourselves heard.'”

son, she votes to advocate for neighborhood schools and improve her and her family’s quality of life.

But voting so far has been challenging. Her first time voting, no one at the polling place she visited spoke Spanish, her native and most comfortable language. She’s had questions while voting in the past, and having in-language assistance would have made a big difference in helping her feel confident in the process, she said.

“For me there is a total difference, from heaven to earth. Huge,” Hernandez said in Spanish.

As the local election office gears up for the November midterms, advocates for new American citizens say a lack of in-language voting materials and assistance at voting centers have made voting harder for communities who primarily speak minority languages.

Laws at the federal, state and local levels require county elections offices to provide in-language voting materials and oral language assistance for voters who speak those languages.

Data from the San Diego County Registrar of Voters shows more than 60,000 eligible voters – out of 1.9 million total in the county as of late September – requested voting materials in Spanish for the upcoming election. Nearly 2,000 requested materials in Filipino, more than 3,000 requested materials in Chinese and more than 7,000 in Vietnamese.

But actually hiring poll workers who speak languages other than English proves challenging each year, according to Cynthia Paes, San Diego County’s registrar of voters.