At the root of San Diego’s recent campaign finance scandal lies the topic of outside donations, and the illegality of foreign money used to influence stateside elections.

Campaign fundraisers and strategists, as well as government employees and independent researchers, all told inewsource the practice is nearly impossible to detect. The main reason, they said, is the overwhelming number of donations that can pour into a campaign. You simply can’t screen every single one.

On the regulatory side, there’s a lack of manpower needed to sift through millions of donations to local, state and federal campaigns. Without a tip or a story in the media, it’s the proverbial needle in the haystack.

Then there’s the anonymity independent expenditure committees offer those looking to spend big.

Add the inability, legally, of asking for citizenship status on donor forms, and the experts agree — it’s a weak system from the ground up.

So Much Paper

K.B. Forbes was the communications director for former San Diego Councilman Carl DeMaio’s unsuccessful campaign for mayor in 2012. He’s a Republican strategist and experienced campaign manager at both the national and local level, having worked both of Pat Buchanan’s presidential campaigns in the ‘90s.

Forbes said monitoring donors is a fool’s errand.

“It is figuratively impossible,” he said, “with the multitude of donations you get in a campaign — and especially now in this electronic age where everything is done instantly through debit cards, credit cards…”

So far, there have been more than 10,000 campaign contributions made during the 2013 mayoral special election. More than 90 percent of those went directly to committees that are controlled by candidates themselves.

“You cannot put the burden on campaigns to verify,” Forbes said. “It’s the people who make the donations who should be held accountable, not the people who receive it.”

That question of accountability is of interest right now in San Diego, where a federal complaint unsealed in late January alleges a group of politicians — mainly candidates for the 2012 mayoral race — received tainted funds from a Mexican billionaire intent on influencing the political scene for his own gain. Allegedly, both independent committees and those controlled by candidates received more than $500,000 from the man, Jose Susumo Azano Matsura, through straw donors and LLCs throughout 2012 and 2013.

Since the complaint was unsealed, politicians have rushed to return contributions and put distance between them and the donors.

Illegal contributions from foreign sources are not a new development. In 1996, the People’s Republic of China was accused of trying to influence American politics by funneling money to the Democratic National Committee.

On a lighter note that same year, author, filmmaker and political activist Michael Moore attempted to expose the hypocrisy of campaign fundraising.

By donating to campaigns through checks labeled with inflammatory organization names — like “Pedophiles for Free Trade” and “Satan Worshippers for Dole” — Moore wanted to show that politicians would accept money from anyone, regardless of the politician’s political or moral viewpoint.

“Michael Moore was trying to show hypocrisy,” Forbes said, “but he didn’t show hypocrisy — he just showed the overwhelming amount of donations you get.”

Anonymity

While the majority of donations tend to be given in amounts up to $1,000 to candidate-controlled committees, big donors use other avenues — independent expenditure committees and PACs — which add a layer of separation between the donor and the donation.

Sheila Krumholz is the executive director at the Center for Responsive Politics, a nonpartisan, nonprofit research group that tracks money in politics and its effect on elections and policy.

“For those who are careful,” she said, “or maybe savvy, it’s not very difficult to mask the true sources of the money, unfortunately.”

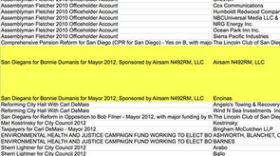

One aspect of the current San Diego scandal revolves around an independent committee, named Airsam N492RM, LLC, which supported District Attorney Bonnie Dumanis’ run for mayor in 2012.

The name itself — Airsam — doesn’t reveal much on first glance. It’s not until someone digs down and looks into that LLC that they would notice it’s owned by Azano, the “foreign national” cited in the initial federal complaint.

But even then, the fact that Azano isn’t a U.S. citizen is only obvious because of his fame in Mexico — he would be much harder to spot if he’d had a lower profile.

“I wouldn’t exactly call it a swiss cheese system,” Krumholz said, “but there are enough holes to make it such that I don’t think anybody seriously thinks that it’s airtight or locked down in any way.”

But what if a candidate does notice that a committee like Airsam — one operating and receiving funds on their behalf — has received donations from a questionable source such as Azano? Legally, candidate-controlled committees and independent committees are not allowed to communicate with each other regarding strategy, donations, or donors.

“I would just build a wall,” Forbes said. “Let their problems be their problems and not worry about who may be giving or who may not be giving.”

“Just avoid it and let the chips fall where they will,” he said.

Others disagree.

One prominent campaign manager, who did not want to be quoted by name because of the sensitivity of the current allegations, said a campaign can make a public statement admonishing the independent committee. That way, the campaign is on the record distancing itself from the donor and the donation, and the independent committee is put in a position where it must acknowledge — and respond to — the donation.

An Overloaded Agency

California’s Fair Political Practices Commission is charged with regulating the state’s campaign finance laws, financial conflicts of interest, and lobbyist reporting, as well as investigating alleged violations of the Political Reform Act.

But Scott Hallabrin, the Commission’s former General Counsel and current staff attorney, said it doesn’t have the resources to search for foreign donors.

According to Hallabrin, the agency has about 70 employees. An average election year in the state brings in more than a million donations.

And it’s not just the numbers that make the search daunting.

As the law exists, the FPPC isn’t allowed to require anything more than a donor’s address, occupation and employer be disclosed at the time of the donation.

Put simply — there is no box to check for “foreign national.”

“It would require statutory change to require them to put citizenship status,” said Hallabrin.

The hope, he said, is that a campaign, the press, or a member of the public will red-flag a donor’s address and bring anything potentially illegal to light.

According to the FPPC’s communications director, Richard Hertz, the agency came under a new, more proactive mandate to enforce these types of violations beginning in 2011 — but it’s historically been a reactive body that responds to complaints and tips.

Even the Federal Election Commission, which is responsible for enforcing similar financing rules on the federal level, has been routinely criticized for its inaction over the last several years. Ellen Weintraub, one of the FEC’s own commissioners, has called the FEC dysfunctional and slow moving.

Krumholz, from the nonprofit that tracks and publishes federal campaign contributions, isn’t optimistic about the future considering the current climate of donor anonymity and lax enforcement.

“If we can’t feel assured in the integrity of our campaign finance system,” she said, “then that’s going to lead people to feel that the game is rigged — that there’s no point in participating.”

“I think that has a much more damaging effect on the democratic process,” she said.

Questions? Comments? Concerns? Reach out to reporter Brad Racino or comment below.