Shortly after Elizabeth George started her freshman year in high school last fall, her parents tested positive for COVID-19. And Elizabeth stepped up to take care of them.

"I was running the house, sort of," says the soft-spoken 15-year-old. "I was giving them medicine, seeing if everyone is OK."

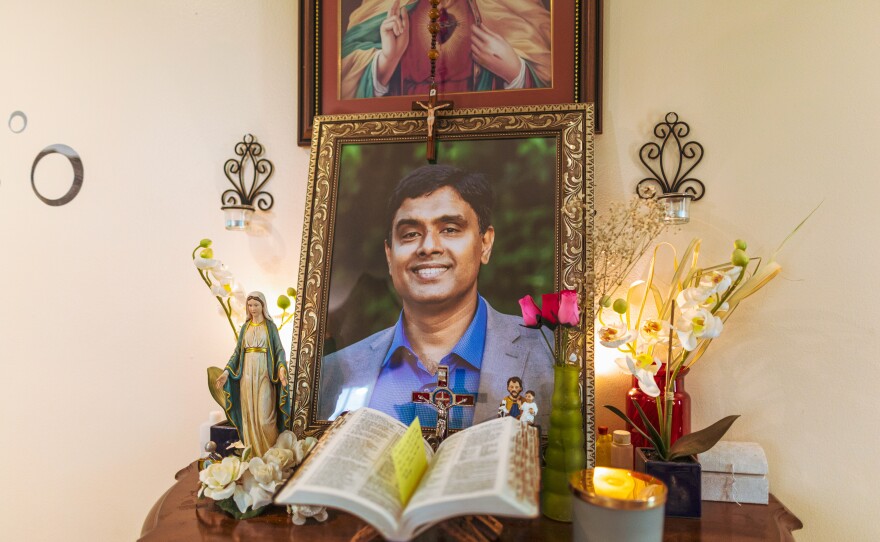

Elizabeth's mother recovered, but her father was hospitalized. He died in September of last year.

His death turned Elizabeth's world upside down. In the weeks that followed, she found herself not wanting to leave her house. "I didn't want to go to school," she says. "I just wanted to stay at home."

When she did return to school at Atlantic Community High in Palm Beach County, Florida, she says, it felt "weird" and "surreal." "Because a few weeks ago, my father passed away and here I am, back to normal, at school. Like, what? How even?"

Like so many kids in her circumstances, Elizabeth felt as if no one at school understood what she was going through. Always a top-notch student, she now struggled to focus at school.

And one day, she found herself feeling alone and isolated in the middle of a crisis. She headed to see the school counselor, but was so flustered that she ended up in the wrong room, breaking down into tears.

Losing a parent in childhood is the kind of trauma that can change the trajectory of kids' lives, putting them at risk of having symptoms of anxiety, depression, post traumatic stress and even poor educational outcomes.

Yet few schools have resources in place to help kids going through this.

The problem has come into sharp relief during the COVID-19 crisis, which left more than 200,000 kids newly bereft of a parent or primary grandparent caregiver, according to some estimates.

"That's like two kids for every public school," says Susan Hillis, co-chair for the Global Reference Group on Children Affected by COVID-19, and the author of several studies estimating the number of kids orphaned by the pandemic.

The educational, mental and physical health costs of not supporting these kids right now could be high, experts warn.

"Honestly, it makes me sick to my stomach to think of the hurt so many kids are experiencing," says Charles Nelson, a neuroscientist at Harvard University who has studied the developmental impacts of separation from caregivers. "We could have done better to protect these kids."

Schools could be the ideal place to help grieving kids, says Hillis, because teachers and counselors know who the children are who have lost a parent or caregiver. And schools are where kids spend most of their time.

Educators are starting to recognize this, says psychologist Julie Kaplow, the executive vice president of trauma and grief programs at the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute.

"The pandemic has helped raise awareness in schools about this," she says, but very often, "schools don't know what it is they should be doing."

Luckily for Elizabeth, a teacher at her school, whose life was shaped by a loss in her own childhood, had started a support group for students like her. It's the kind of support mental health experts say schools all over the country need to be investing in.

Finding a safe space at Steve's Club

The day that Elizabeth melted down at school, she ran into teacher Cori Walls, who was concerned for the freshman and asked her how she was doing.

"All of a sudden I started crying," recalls Elizabeth.

Walls understood what the teenager was going through, because she, too, had lost her father when she was young – a loss that had haunted her entire childhood.

"I can remember being jealous of seeing girls with their fathers when I was little," says Walls.

Her pain became more pronounced when was a teenager. She remembers feeling particularly sad about not having her father see her graduate from junior high, and then again as a senior in high school. "I went back to visit his grave, and that's when grief smacked me in the face," she says.

Walls felt alone in her sorrow – neither her family, nor anyone at school knew how to support her.

So, years later, when Walls became a high school teacher, she paid attention to students who were grieving for a parent.

"When I first walked into the classroom – my first period class – I had four students that I met that had lost a parent," she says. "And I immediately could identify and understand what they've gone through and what they were dealing with."

Walls began keeping track of these students every year. She had an open door policy with them – always available to listen to them, and provide additional academic support.

Then, in 2019, she had 10 such students in a single class. "After that happened, I just couldn't sit down and not do anything about it," says Walls. "So I asked my principal at the time if I could start a group to get the kids together."

She named the group Steve's Club, after her father. It is open to any student grieving the loss of a parent, a caregiver or sibling. The group meets twice a month to talk about what they are going through.

![Cori Walls lost her father at a young age and started Steve's Club, a grief support group for students. "I just wanted them to know they weren't alone," says Walls. "What I envisioned [is] kids just getting together and sharing their story and being there for each other and knowing that somebody else understands how they feel."](https://cdn.kpbs.org/dims4/default/dce79f9/2147483647/strip/true/crop/6720x4139+0+169/resize/880x542!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.npr.org%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2022%2F07%2F12%2Fgrief-club-5_custom-f08dbcc527cef944aaa8e8d33565685260ec09c3.jpg)

But in the years since its launch, the Club has become more than a peer support group. Walls brings in local mental health professionals to provide grief counseling to the students. She refers students who need additional care to school mental health care providers. And she is always available to the students, to listen to their struggles and advocate for them.

"I help them find volunteer hours, I help them find part time jobs," says Walls. "I obviously have communication with their teachers. But at the end of the day it's so that they just know that they're not alone."

The growing membership of the Club is a testament to the needs it's serving – this past academic year, there were 80 members, most of whom had lost a parent or primary caregiver. And it's a diverse group of kids, says Walls, who would likely not have not connected with each other on campus had they not met in the group.

"There [are] children from all backgrounds – socioeconomic, ethnic, racial, religious, sexual orientation, whatever it is," she says. "They forge these bonds with each other and respect each other."

It was exactly what Elizabeth needed after her father died. When the freshman ran into Walls that day, she also met a member of Steve's Club – someone who had lost her father during the pandemic.

"It was kind of a similar experience, so we were able to talk things out," says Elizabeth. "And it made me feel a lot better."

Soon after, she found herself at her first Steve's Club meeting. "I could tell it was a very safe place for me, for everyone actually," she says. "It was eye-opening."

Schools are where you can reach kids

School-based grief support groups like Steve's Club are rare, but "a great idea," says Kaplow.

That's because "peer support can be extremely beneficial," to bereaved kids, she adds. And grief counseling can teach kids about the grieving process, as well as basic coping skills that are "universally helpful for any kids' grief."

The Steve's Club model also allows schools to identify kids who need additional mental health support and individual therapy, says Kaplow.

For schools to become a source of solace and healing to kids who have lost parents, the first problem, says Hillis, is figuring out who the children are who need help.

The new wave of kids bereaved by COVID comes on top of all the children whose parents died from every other cause, from cancer and heart disease, to accidents and drug overdose.

And many of these other causes "are often indirectly related to COVID, as decreased access to health care for other problems was rampant during the pandemic," says Hillis. And "in many situations we really don't know who [these] children are."

There's no national, or regional efforts to identify these kids and support them. So, the vast majority of children experiencing the death of a parent or caregiver grieve in isolation, which worsens the impact of the trauma.

"Bereavement is the number one predictor of poor school outcomes, including poor school grade, school dropout, school truancy, lack of school connectedness and problems learning," says Kaplow.

It can lead to everything from longer-term depression, suicide risk, substance abuse and problems with relationships, she adds.

"When children who are grieving do not get the support they need they may actually become stuck in their grief," says Kaplow. "Their worldview can change completely into something like the world is a scary and dangerous place. Nobody is safe. I'm not safe. And that can create more anxiety over the longer-term."

School and community-based interventions are a key component of recommendations by the COVID Collaborative, a group that's been raising awareness about kids orphaned by COVID-19. The group calls for a big push to identify kids orphaned by COVID, as well as grief sensitivity training in schools, so school staff are better prepared to support bereaved students, and expanded mental health support in schools.

Despite calls from this organization and researchers like Hillis, the Biden administration hasn't announced any efforts or funding to help COVID orphans.

"Because people view bereavement and grief as normal parts of life, these are not necessarily issues that are brought to people's attention quickly," says Kaplow. "People don't quite know what to look for after a child loses a caregiver or a loved one ."

But there's an urgent need to support grieving children, she adds.

Her institute is increasingly working with schools to expand support for kids, training school staff "to provide evidence-based support" to grieving children. "The idea is to train not only school counselors, but also teachers to understand what grief can look like in different stages," she says.

She's also teaching them ways to create "a grief-informed classroom," so that they know what "red flags to look for to identify which kid needs more support."

Walls, who runs Steve's Group, thinks schools are the right place to invest in helping kids.

"There's plenty of grief support out there, but they're not getting connected to all the kids that actually need it," she says. "I would love to see a position created within the school districts that will allow a person to connect to all the support outside the school district and within the school district and then connect them to the kids."

'Let us know how you feel'

![Students share their experiences during a group session at Steve's Club. "[The club] helped me to realize there's other people who have also had their parents or father or their mother pass away," she says. "And now I know there's someone I could talk to that can understand."](https://cdn.kpbs.org/dims4/default/6a72ce8/2147483647/strip/true/crop/6720x4139+0+169/resize/880x542!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.npr.org%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2022%2F07%2F12%2Fgrief-club-3_custom-434be1a5cf42dc387f5551459a0a11fd9ede4b28.jpg)

Though it's just one small group, in one school district among thousands around the country, Steve's Club shows how effective a school-based grief group can be.

One day this spring, Elizabeth was among a dozen students from across the school meeting in a classroom – students whose parents died due to everything from COVID to stroke and suicide.

The meeting started with pizza and chit-chat, students joking with each other between bites. But soon, everyone became quiet, and settled into their chairs.

"Let's go around the room, say who you are, and who you're here to remember," said Walls. "And let us know how you feel."

After the introductions, Felise Jules, a therapist with Palm Beach Youth Services talked with the students about the basics of grief.

Jules, who had lost her mother in childhood, also shared her own experience of grief – how she spent years in denial.

"I truly believed that if I pray more, my mom will come back,"" said Jules. "If I've been good in school, if I have straight As, my mom will come back."

Sitting next to her was a tall, lanky boy, his long legs stretched out in front of him. He sat up to share the depths of his depression after his mother died four years ago.

"What went through my head at that time was, I want to see my mom again, so the only option was suicide," he says.

Another student spoke about having considered using substances to cope with her loss. Yet another shared a nightmare she had after her father died. Walls, too, spoke about her own struggles, years after her father's death.

Suicide, substance abuse, nightmares – not easy things to talk about to a room full of teenagers. But with her warm smile and no-nonsense manner, Cori Walls has created a space where students feel comfortable sharing their darkest moments.

Understanding and respecting others' grief

When students start to heal through these sessions, many want to see their family members heal as well. And Walls has an open door policy, so that students can invite family to stop by during a Steve's Club meeting.

At the recent meeting in May, 14-year-old Luca brought her father.

"I wanted him to see what it was like to get some sort of help, and some therapeutic experience that makes you feel better and more understood," she said. Her mother died by suicide in 2016 and she'd had no grief support until she joined Steve's Club this January. (NPR is using the family's first names only to protect their privacy.)

Her father, Eric, a tall, broad shouldered man in denim, sat quietly in the back of the classroom.

After the meeting, he told me that he tried to cope with his wife's death by staying busy.

"Taking care of three kids is pretty demanding," he said. "And working full time."

When I asked him how he was doing, he said, "good," but his voice choked, as he fought back tears.

Even after all these years, his grief was raw. His daughter sat next to him, holding his hand, comforting him as he broke down.

"I'm not a huge fan of talking about my feelings," he said, his voice still shaking.

But he was happy to see his daughter's generation opening up.

"It's just absolutely wonderful for the kids to just sit down and talk about their feelings. I know if I was to do that at my school, I would have gotten beat up," he said with a laugh.

Luca's much happier since joining Steve's Club, he said, and "probably does a better job of coping than the rest of us."

Parents and caregivers are "grief facilitators for kids," Kaplow explains.

"Providing all the support to kids is critically important, but even more important is making sure that caregivers get the support they need," says Kaplow. "If the [surviving] caregiver is still struggling and stuck in their grief, that's going to be prohibitive in helping their child to grieve in a healthy, adaptive way."

After three years of running Steve's Club, Walls says she was moved to see the reaction of the rest of the group to seeing Luca's dad break down.

"Instead of being immature, they were like 'our heart's breaking right now," says Walls. "They were like, "Luca's so strong. Look at Luca holding her Dad's hand'."

She says that's when she realized the value of the work she's been doing.

"Because I know my kids understand grief, they understand it's real, and they respect other people's situation."

And she knew that she had created a space where grieving students are creating long lasting friendships that will buffer them from their trauma.

"Now they have this special group of kids that they know have their back and it's all based on their loss," she says.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))

![Elizabeth George, 15, was a freshman in high school when her father died from Covid-19 last October. Since his death, she has struggled to regain a sense of normalcy. "I have difficulties even going [out] with my friends," she says. "I just want to sleep at home."](https://cdn.kpbs.org/dims4/default/ab4675f/2147483647/strip/true/crop/6614x4074+0+195/resize/880x542!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.npr.org%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2022%2F07%2F11%2Fatlantichigh_florida_033_custom-21a2aceb9048a7a701a167bf408f001be8446fcd.jpg)