Astronomers are lining up to use a powerful new NASA telescope called SOFIA. The telescope has unique capabilities for studying things like how stars form and what's in the atmospheres of planets.

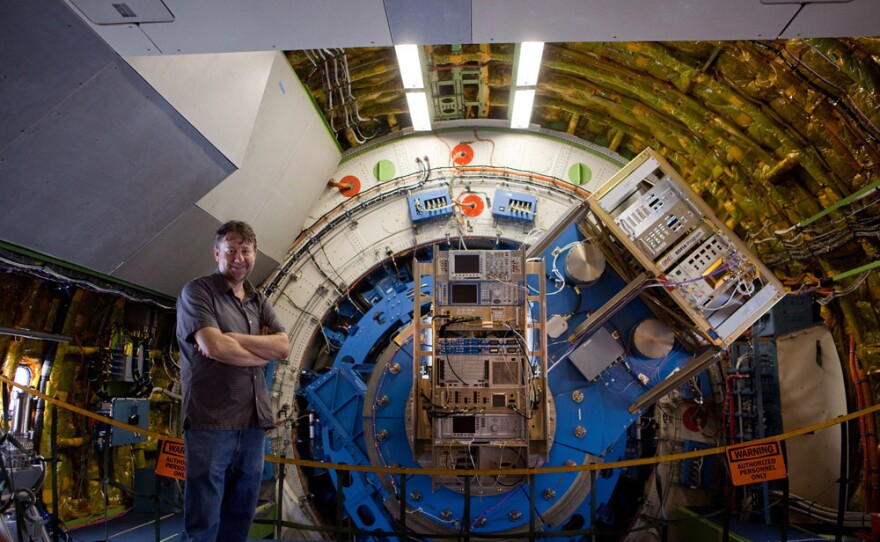

But unlike most of the space agency's telescopes, SOFIA isn't in space — it flies around mounted in a Boeing 747 jet with a large door cut on the side so the telescope can see out. Putting a telescope in space makes sense: There's no pesky atmosphere to make stars twinkle. But why put one on a plane?

One reason is that the plane lands every day, says Alycia Weinberg, an astronomer at the Carnegie Institution for Science. She's in charge of planning observations on SOFIA, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy. Weinberg says those daily landings let researchers fix things or upgrade instruments. With no more space shuttle missions, fixing telescopes in space ranges from nearly impossible to impossible.

Another reason a flying telescope makes sense is that at 45,000 feet, you're above most of the moisture in the atmosphere. For astronomers, that's important, because water vapor makes viewing the sky at infrared wavelengths impossible.

Like sounds that are too low or too high for our ears to hear, infrared wavelengths are light that the human eyeball can't see. But they're there, and Weinberg says lots of things glow at infrared wavelengths like "the cocoons of dust that old stars give off as they go through their final stages of life." Those cocoons of dust are where new stars come from.

One of the things astronomers especially like to do with light from distant objects is put it through a spectrometer. That's an instrument that can reveal the kinds of atoms and molecules that are in the light from whatever the telescope is pointed at. David Neufeld, a professor of physics and astronomy at Johns Hopkins University, has big plans for one of SOFIA's spectrometers.

"I'm looking for a small molecule composed of one sulfur atom and one hydrogen atom," Neufeld says. "It's called mercapto, and it's never been seen before in the interstellar gas."

Neufeld will be observing a cloud of gas in the interstellar space between Earth and a patch of space with the memorable name W49N. The reason Neufeld is interested in mercapto radicals is that they form at certain temperatures.

"So if we see it, what it will tell us is that the clouds of interstellar gas that we are looking at, which are thought to be very, very cold, may have parts of them where it's been heated up to much higher temperatures," he says.

And that information will help explain how new stars form out of these clouds of gas. This is one of those rare times in science when there might actually be a eureka moment. Neufeld says if it's there, mercapto will show up as a line in a readout from the spectrometer.

"[We] may see nothing, the instrument may not work, but hopefully pretty quickly we'll see a hint of the line. So hopefully it will seem like a eureka moment, anyway," he says.

A Delayed Discovery

Neufeld was supposed to board SOFIA at Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington, D.C. It stopped at Andrews on its way from an air show in Germany to its home base in Palmdale, Calif.

That was the plan, anyway, but the night before the flight, the NASA press office called to cancel the trip. John Gegosian said there were two reasons: "First, there's a cooling fan for the telescope that malfunctioned. The second reason was the weather."

It had been raining heavily all week in Washington and the forecast called for more. Flight rules say SOFIA can't take off in a rainstorm because water might get into the telescope's sensitive equipment. So no scientific observations on the way back to Palmdale, and no passengers.

A few days later the fan was fixed, and last Tuesday night SOFIA was able to observe Neufeld's interstellar gas cloud. Neufeld couldn't make it out to California for that flight, so he waited by his computer for an email with the results. It came right after the plane landed Wednesday morning.

"It was immediately obvious that we had an absolutely clear detection of the mercapto radicals, so I was absolutely delighted," he says.

A sort of virtual eureka moment.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))