In the jargon of the Supreme Court, we talk about "landmark cases." Some, of course, are more landmark than others. But by any yardstick, the June 2006 ruling in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld was one for the history books.

Hamdan was the case in which the high court invalidated the system set up by President Bush to try accused war criminals at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The court's 5-3 decision is widely seen as the most important ruling on executive power in decades, or perhaps ever.

But cases like this do not materialize out of thin air, and the Hamdan case, like Brown v. Board of Education, was carefully nurtured, with the defense lawyers facing a constant stream of difficult issues. A wrong decision at any point could have ended up aborting the case.

It all began in 2003 when a handful of detainees at Guantanamo were designated for possible prosecution as war criminals. They were to be the first of what the Bush administration anticipated would be a continuing series of prosecutions.

Guilt as a Condition of Defense

If convicted, the defendants could be subject to the death penalty. Although no formal charges were brought immediately, the first group of six was, upon designation, moved into isolation — what in a regular prison would be called solitary confinement.

As the year drew to a close, charges still had not been brought, but one of the military defense lawyers, Navy Lt. Cmdr. Charles Swift, got a letter appointing him as counsel for a Yemeni citizen named Salim Ahmed Hamdan. Hamdan, who had served as a driver for Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan, was captured by the Northern Alliance and turned over to U.S. troops.

There was just one hitch to Swift's appointment as defense counsel: The letter told Swift that his access to his client was conditioned on his negotiating a guilty plea. Swift thought that was an unethical condition.

He immediately called Georgetown law professor Neal Katyal, who by then was on board as the civilian lawyer for the military defense team. Katyal, 33, had volunteered his services and been embraced by the defense team. He had worked for two years in the Clinton Justice Department on national security issues, so it was easy to renew his security clearance.

More importantly, Katyal had been an early academic critic of the Bush military tribunals. He had written, thought about, and testified on the issue. So, he was the perfect point man for developing a legal strategy aimed ultimately at Supreme Court review.

The Decision to Fight

Katyal and Swift were worried that if Swift went to talk to Hamdan and Hamdan didn't want to plead guilty, Swift would be barred by the military from seeing his client again, and would be unable to represent him in court. To avoid that, Katyal drafted a legal document for Swift to take with him for his first meeting with Hamdan.

Swift took the document to Guantanamo and explained the options to his new client. Hamdan could plead guilty or he could fight. If Hamdan chose to fight, he might not see Swift again, the commander told him, "but understand I will start fighting and keep fighting for you the entire time."

Hamdan said he didn't want to plead guilty, and signed the document Katyal had drafted: an authorization for Swift to file a legal challenge on his behalf.

Finding Friends in Seattle

Swift filed a motion demanding a speedy trial and was promptly informed that Hamdan had no right to one. Swift then prepared to file a lawsuit as Hamdan's "next friend" in federal court in Seattle, challenging the military tribunal system.

Swift and Katyal chose Seattle because they wanted to get away from the two federal appeals courts where the Bush administration loved to litigate — the 4th Circuit in Virginia and the District of Columbia Circuit in the nation's capital. Both of those courts were populated with Bush and Reagan appointees who had consistently sided with the administration on national security issues.

It made sense to file in Seattle. It was Swift's legal residence because it was where he lived when he joined the Navy. But neither Swift nor Katyal was licensed to practice law there.

Just as Katyal was pondering approaching some law professor in Seattle to act as local counsel, one of his former law students called him about something else. The former student was at Perkins Coie, one of Seattle's leading law firms. By that night, the managing partner of the firm was on the phone with Katyal, pledging major help, including partners who would work on the case for the next three years. Katyal notes that at the time, most law firms were steering clear of Guantanamo cases for fear of being called unpatriotic. Perkins Coie, he says, was particularly brave in volunteering to help so early.

The defense team for the war crimes defendants by then had settled on Hamdan's case as the one they wanted to use in challenging the military tribunals. Swift focused on Hamdan after watching a documentary about the Nuremberg trials in which he noticed that Adolph Hitler's driver was not prosecuted as a war criminal.

"They didn't prosecute him. They interviewed him," notes Swift, adding that, "in the law of war, the idea is to charge the principals, not the foot soldiers, unless of course, the foot soldiers are lining up civilians and shooting them."

Katyal knew the defense would take a public-relations hit for defending Bin Laden's driver, but he says that "Hamdan stood out as being the one who had done nothing bad himself, besides being the driver to a bad guy." That, says Katyal, contrasted with the records of others who had "actually picked up guns, shot people, and the like."

Detention Takes Its Toll

As the months dragged on, though, Hamdan, who remained in solitary confinement, went into a spiral of depression. He wasn't on a hunger strike, says Swift, but Hamdan was so depressed he stopped eating and drinking, and his guards became alarmed at his deterioration.

Swift, despite his fears that he would lose access to his client, had not been cut off, and he now got hold of a photograph of Hamdan's children in Yemen and brought it to the prison. Upon seeing the photo, Hamdan "just broke down sobbing," says Swift. Knowing Hamdan was himself an orphan, Swift asked his client, "How can you leave them" the way you were left? And suddenly, Hamdan reached for a drink of water.

While all this was going on, the Supreme Court announced that it would decide whether the other detainees at Guantanamo — those not charged as war criminals — had a right to challenge their detentions in court.

The Hamdan lawyers saw this as an opportunity, and they notified their superiors of their intention to file a friend-of-the-court brief in the regular detainees' Supreme Court case. If their superiors wanted to bar the brief, they could, but the letter to the military higher-ups cc'ed Neal Katyal, the defense team civilian lawyer, who was not in the chain of command. That cc, says Katyal, was designed to let the powers-that-be know that "there would be repercussions if they decided to gag the lawyers."

The Rules Change

According to Bush administration sources, some administration officials wanted to veto the brief, and a decision on the matter went all the way up to the White House. But in the end, officials there decided it wasn't worth the hit they would take in the press, and the brief was filed, amid considerable fanfare.

The filing of that friend-of-the-court brief, says Swift, "changed the rules forever. We'd been told we would never talk to the press, we would never be seen. We would simply sit there, take it, and then it would be over. It was to be a one-way show." The brief," he says, "gave us an opportunity to break out."

In June 2004, the Supreme Court ruled that the regular detainees could go to federal court to challenge their detention, and for technical reasons, the Hamdan case was moved back to Washington, D.C.

Five months later, Katyal went to Guantanamo to meet his client for the first time. Hamdan, who comes from a culture of gifts, gave the lawyer what Katyal calls "literally the only possessions he had," a few prized sweets — a date and some raisins.

He had just one question for the lawyer: "Why are you doing this?"

As Katyal recounts the meeting, he told Hamdan: "I am doing this for you because my parents came from India to America" for one simple reason, "America doesn't treat people differently because of where they come from. We fought a civil war in part about the idea that all people are guaranteed certain rights, and chief among those is a right to a fair trial."

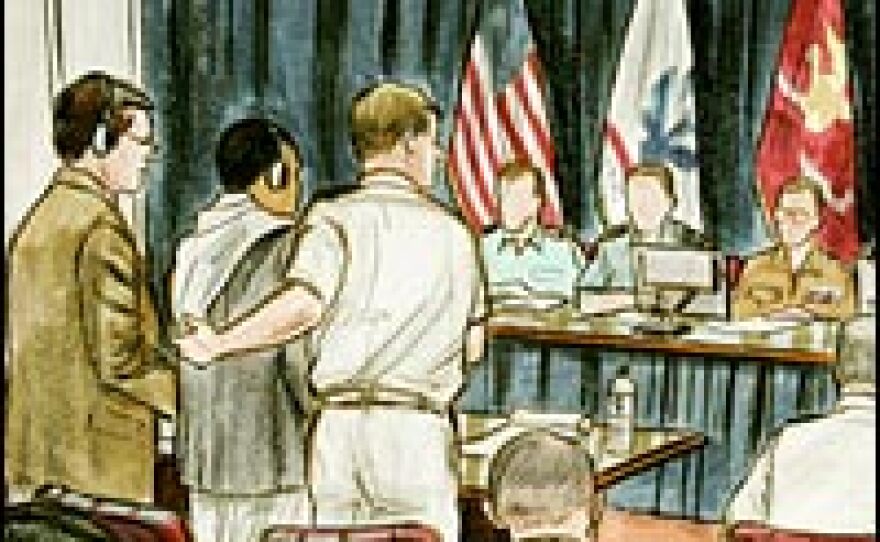

Days later, federal Judge James Robertson struck down the military tribunals as unconstitutional. At a pre-trial hearing for Hamdan at Guantanamo, there was "mayhem," in Katyal's words, as news of the decision filtered in. The military judge abruptly called a halt to the proceedings.

The victory for the defense, however, was short lived. A federal appeals court panel that included then-Judge John Roberts (who later became the chief justice) overturned the decision eight months later.

Now the defense was fully focused on persuading the Supreme Court to accept the case for review. In August 2005, Katyal filed a brief in the Supreme Court contending that the rules the president had established for the tribunals were blatantly unfair and unconstitutional.

In response, the Bush administration changed some of the rules — for example, to allow evidence obtained by "coercion" but not "torture." Katyal then wrote a reply brief contending that these very changes proved his point: The rules were not rules at all, but an ever-moving target, a system not approved by Congress, that worked at the whim of the president.

The Senate Steps In

On Nov. 7, 2005, the Supreme Court announced it would hear Hamdan's case. Three days later, Sen. Jon Kyl (R-AZ) introduced legislation he had been working on with the administration to strip the courts of jurisdiction in the Guantanamo cases. The legislation quickly passed in the Senate, with the aid of Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC).

The defense team, led by Katyal, went into high gear to get the language in the bill changed to exempt pending cases, so that the Hamdan case would stay alive. The Senate did in fact change the language in the bill, and now there was another issue before the court — whether Congress had intended to keep the case alive.

Getting Ready

In the months that followed, Katyal, who had never argued a case before the Supreme Court, devoted thousands of hours to preparation. He made a list of the lawyers across the country who intimidated him the most, and flew out to do dry runs in front of them. In all, he did 15 practice sessions.

At the same time, he was writing not just his own brief, but coordinating some 40 friend-of-the-court briefs filed by human-rights organizations, groups of high-ranking retired military officers, diplomats, historians, and conservative as well as liberal legal scholars. Such was his attention to detail that he ran a videotape of the Senate debate on stripping jurisdiction and was able to tell the Supreme Court which statements were made during the floor debate, and which ones were inserted later, after the debate was over, to try to give the debate a different gloss.

In all, about 1,000 lawyers and law students worked on various parts of the case, with Katyal acting as major-domo, listening, parsing and weighing divergent views on how to frame the legal arguments.

The work was so fast and furious that for well over a year, Katyal — a husband and father — never got more than four hours sleep a night. And no week passed without at least 3,500 e-mails. Even his own pocketbook was tapped. He spent $40,000 of his own money on the case.

It all paid off on June 29 with Katyal and Swift in the courtroom, when the Supreme Court sided with the defense on almost every point.

It was a stunning rebuke to the president. But Katyal doesn't see it that way. He commends both the military and the administration for letting him and Swift do their jobs. "In some other country," Katyal observes, "we might have been shot."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))