The first day Patty Lee returned to school in 1967 after her father was killed during the Vietnam War, a classmate approached her with a message.

“My parents said your dad deserved to die,” the classmate told 12-year-old Lee.

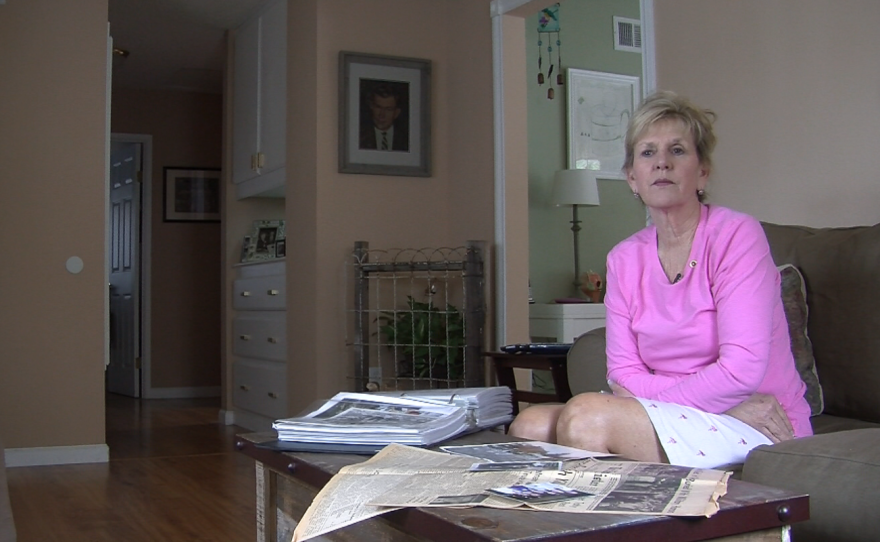

Now a 60-year-old grandmother, Lee said that experience taught her to stay silent about her father’s service in one of America’s most unpopular wars.

“From that I learned when people asked ‘Where is your father?’ ‘My father died when I was 12,’” Lee said, struggling to keep her voice steady and her eyes dry. “My mother was: ‘I’m a widow with six kids.'"

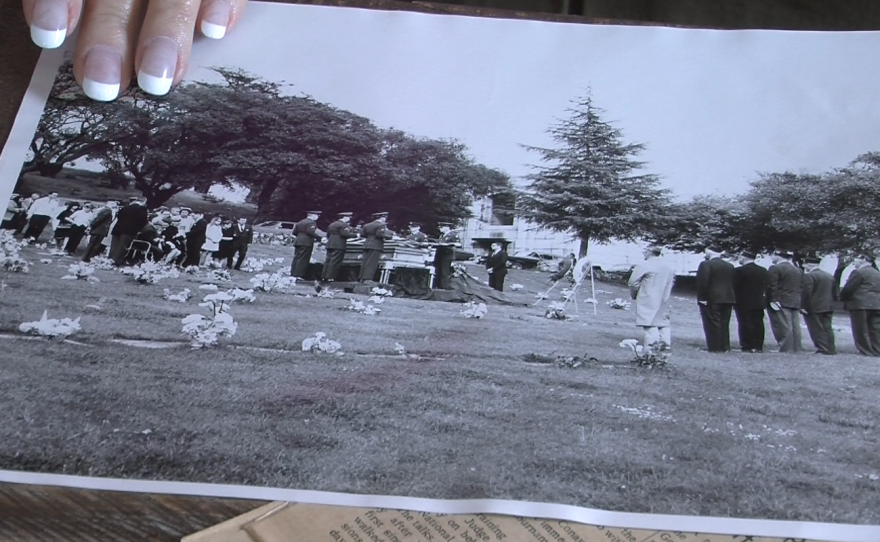

Lee said she barely uttered her father's name until a 1992 trip to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. At the 500-foot black granite monument that bears the names of the more than 58,000 U.S. service members killed in the war or who remain missing, Lee connected with other children who lost their fathers in Vietnam.

She was 37 at the time of the visit.

“Then, it was like I was 12 years old,” she said. Her voice breaks and the tears spill over. “And that’s when my first grieving really began."

Lee’s experience highlights the power of the massive landmark that attracts millions each year. But for many more, the memorial is physically and financially inaccessible. (Even Lee had to spend weeks fundraising so she and her siblings could make that first trip.)

For people like Lee and her family, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund created a wall that travels to their hometown.

It’s called The Wall That Heals — a half-scale replica that travels 30,000 miles to 30 cities each year.

Tim Tetz, public outreach director with the memorial fund, said the wall brings solace to an era of veterans and families who grieved in silence after a divisive America literally spat on service members returning from the Vietnam conflict.

“The mere presence, the ability to reach out and touch that name and to grasp that, and to have those emotions that come with it, at times, is very painful and at times, brings tears to many grown men’s eyes,” Tetz said. “But then you start to have that healing and you start to have that laughter and those stories, and that’s what it can do when it comes into a community."

Just in the last few weeks, Tetz said he’s encountered a father who visited the wall to find the name of a son he never knew he had, an ailing veteran who never shared his war experiences with his children until he saw the inscribed names of his comrades, and a son who was just a baby when his father was killed in Vietnam.

Since the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund’s traveling wall first launched in 1996, it has visited more than 400 communities, but Tetz said the timing and location of this year’s stop in San Diego is a special occasion. It reunited the 58,300 U.S. service members who died in the conflict with the vessel that saved thousands as the war ended.

The 140-panel wall has been on display on the deck of the USS Midway for 24-hour viewing since April 25 and is open to the public until Thursday at 5 p.m. The aircraft carrier was part of an unprecedented rescue operation that saved tens of thousands of Vietnamese from the capital city of Saigon when it fell to enemy forces on April 30, 1975. Thursday marks the 40th anniversary of the end of the war.

Since Lee’s visit to the national memorial in 1992, she’s able to speak freely — although tearfully — about her father, Delbert C. Totty, an Army platoon sergeant who served nearly two decades in the military.

Her father called her “Pete,” maybe because she was the third daughter and her father had been waiting for a boy, Lee joked. She grew up as a tomboy and remembers secret trips to the pastry shop with her dad to share glazed donuts, their favorite. She was the first to step up when her father needed help with tools, moving furniture or building a fence around her family home in Napa, which is the last thing she did with him before he deployed to Vietnam.

Today, a chipped and rusted piece of that fence sits in her living room at her home in San Diego, where her family moved shortly after her father was killed. It’s one of the many relics of her dad’s life and death that she’s collected over the years since her Washington, D.C. trip.

Since then, she’s spent many hours helping others experience the same solace she has. After Lee visited the national monument in the spring of 1992, she learned one of the traveling walls was coming to a nearby town that fall.

“I went to that moving wall and I sat down with the directory to help people find a name,” she said.

Three aged copies of the thick green volume sit on the bookshelves in her living room.

“It was a weekend of nonstop crying because every name I looked up, I cried. But I was learning. I was learning and I was healing and I was helping someone else," Lee said.

When you go to the wall, you can find Lee sitting at a folding table with copies of her directories and a box of tissues.