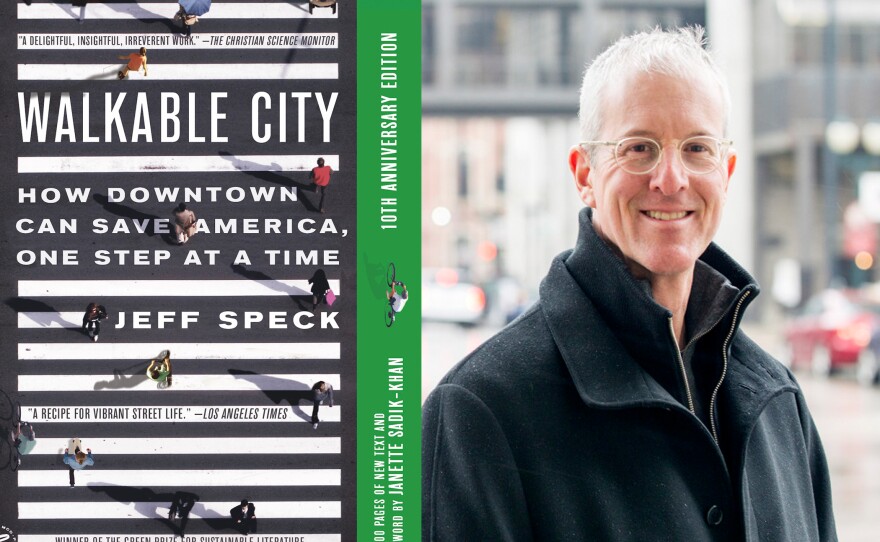

In his book "Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time," author and city planner Jeff Speck makes the case for transforming America’s cities away from cars, toward a more walkable future. He has now published an updated 10th anniversary edition of his best selling book with more lessons for cities like San Diego.

Speck joined Midday Edition Thursday to talk more about what he's learned about walkability in the 10 years since the book was first published. The interview below has been lightly edited for clarity.

You have called cars the central problem of American life. Why?

Speck: I grew up really loving cars. I had subscriptions to "Car and Driver" and "Road and Track," and I could name every car from the school bus. That was my special skill as a child. But the more that I've studied cities and the more that I've worked in cities, the more I've realized that not banning cars, but putting the car in its place, not allowing the car to dictate the shape of the city, is the key factor in how livable and how healthy cities are.

In your book, you write about Rome, and how it really shouldn't be a walkable city, yet it is considered one of the top walkable cities in the world. Can you explain what you mean by that and what lessons it may have for cities like San Diego?

Speck: When I talk about walkability, I mean making places where people will make the choice to walk. And if people are going to make the choice to walk, the walk has to be as good as the drive. And that means, actually — according to my general theory of walkability — it has to do four things simultaneously: It has to be useful, safe, comfortable and interesting. What makes Rome amazing is that it violates a lot of the rules about what makes for a(n) easily walkable, certainly an accessible sort of streetscape. But the fabric, what surrounds the streets is so darn useful and so comfortable and so interesting that everyone makes the choice to walk there, because it's just so darn delightful.

I think when it comes to American cities, it's much more important to focus, as I do professionally and certainly in "Walkable City" and in this new update to "Walkable City," specifically in that safety category, because what we get so wrong in the U.S. — and so many places — is designing streets for safe walking and safe driving.

It's been 10 years since your book was originally released. What has surprised you most over the last 10 years when it comes to walkability?

Speck: The biggest gains in those last 10 years have probably been in Europe more than in the United States.

But the chapter in "Walkable City" that I knew I was going to have to rewrite was probably the cycling chapter, because that's where the most advancement has been happening the quickest all over the country, not just in the usual suspect, leafy, liberal places. But we've been adding bike lanes all over the U.S. And the technology, you're probably aware the quality of the bike lane, the advent of the protected bike lane, the buffered bike lane, bike lanes that are called low stress facilities where you don't really feel endangered when you're riding your bike in traffic. That's been the thing that we've seen landing on the streets of many American cities. We can do a lot better, but that's been an impressive change.

Well, when I moved here to San Diego five years ago, one of the things that I noticed was that there wasn't really any infrastructure for bikes. And that was surprising given the good year-round weather that we do have. I know that one major focus for the city of San Diego recently has been adding separate bike lanes. Its latest effort is happening in the Convoy district, a very car centric part of San Diego. How do bikes and bike lanes fit into this conversation on walkability?

Speck: Well, the city in which people are biking is actually a much safer city for walking, so they work together quite well. When one cyclist hits one pedestrian, it runs in the headlines for a week. Of course, cars are the real threat to pedestrians, not bikes. And when you have a city that welcomes biking, people are making the choice then perhaps to drive a bit less and to instead switch over to that biking, transit, walking lifestyle. When a bike network is truly useful, when you can get where you need to go across the city on a bike, that's when people make the choice.

I'm encouraged that you use the word infrastructure because people talk about culture, and they talk about how people bike in certain places, and don't bike in other places. What we found is that biking culture follows biking infrastructure. There's nothing different about people in different places that determines whether they're going to bike or not. In fact, weather and topography, whether you're hilly or not, have a much smaller impact than you would think. More people bike in hilly San Francisco than in flat Los Angeles. And of course, some of the best biking places are winter communities. But when you build that infrastructure, that's when you generate the biking culture. And the frustrating thing is that you can build a lot of it, but if it isn't enough to form a useful network, then you won't see that change in behavior. But at some point, you cross that threshold, suddenly biking is useful. And that's when you get the population.

You focused a bit more on biking in this updated version of your book. What else did you not cover in the original version?

Speck: Well, I think I learned a few lessons I wasn't that sure about really came home to roost. The biggest one, I think, that pertains to San Diego is that the typical street in San Diego, especially downtown San Diego is not a safe street. The lanes are too wide. They're probably eleven or 12 feet wide instead of 10 feet wide, which is the standard.

Remarkably — and this is something that we've been fixing all over the country — they present themselves in this one-way pair system. A lot of the streets in downtown San Diego are multilane one-way streets. One thing that about 85 different American cities have done, and I've probably worked on about six of them myself, is converting these high speed multi-lane jockeying from lane-to-lane one-way systems back to two way. City after city are doing this, and when they do it crashes and injury crashes drop precipitously. So that's something that you could definitely do in San Diego.

The other thing that's really changed in 10 years — I didn't really have the courage of my convictions 10 years ago, but now we have a lot more data — is that when you replace signalized intersections, intersections with signals with stop signs, then the crashes drop precipitously. In fact, severe pedestrian injury crashes drop by 68% when you replace a signal with an all-way stop sign. And if you think about it, it makes sense because no one's ever speeding through an all-way stop sign, unless they are dramatically breaking the law whereas people are speeding through signalized intersections all the time to beat the red or just because that green light is an invitation to speed after waiting at the previous signal.

The one thing I would add to that, contrary to people's expectation, is that when you replace signals with stop signs in the downtown you can actually drive through the downtown more quickly. You're traveling slower, but you actually get through the city faster because you're never sitting at a light.

What would you say to someone who remains unconvinced that a city like San Diego can move away from being a car dominant city?

Speck: You play the hand you're dealt. I've worked in cities as transit friendly as Boston, where I live, or as transit unfriendly as Oklahoma City where they say you're never going to get the cowboy off of his horse, and you are able to make changes in any of these places. It isn't an on-off switch.

It isn't that you either have a walkable city or you don't. The question is how walkable is your city? Are some people able to perhaps lose one car per family? Or some people maybe have no cars per family. But the more people you have walking, biking and taking transit and the fewer people you have driving the more productive economy you're going to have, the higher GDP you're going to have. The statistical correlations are so strong between walkability and almost any measure that you can consider in terms of a city's success: more patents per capita, higher GDPs, more creativity, healthier, slimmer populations.

A study was done in San Diego that found out that 60% of residents in a low-walkable neighborhood were overweight, compared to only 35% of residents in a high walkable neighborhood. And you find that nationally, our cities aren't so much different from each other as parts of cities are different from each other. The more car dependent a part of a city is, the less healthy the people are going to be, the worse the air quality is going to be.

What are some simple steps cities can do to make its streets more walkable, and also to bring more equity to neighborhoods?

Speck: The two fundamental laws of good planning are bring density to transit and bring transit to density. But on a street by street, neighborhood by neighborhood basis, it is just so important to design the streets for the speeds which you want the vehicles to travel. And that's a fundamental difference between the U.S. and Europe. We have these vision zero policies where the goal is to have zero traffic deaths per year. And in certain countries, in certain cities like Oslo and Stockholm, they actually (had) zero traffic pedestrian deaths last year. I mean, it's astounding in the U.S. you have hundreds. In fact, I read that 294 pedestrians were killed in traffic collisions in San Diego last year. That's an incredibly high amount. The reason is that in Europe, they determine how fast they want cars to go, and they design streets to only allow drivers to feel comfortable when they're driving that speed.

One other final thing, you have this new statewide mandate in California where local municipalities are losing the ability to make (a) choice about providing new housing. It's becoming state mandated. These are a good step. I support these. However, in the absence of good planning, they're really dangerous because you can end up with some really bad and ugly and socially unfriendly buildings.

There's another technology called form-based codes, which replace the typical statistical base and zoning based codes that we have in our cities with actually describing the shapes of buildings and how they meet the street and how friendly they are to the sidewalk and where the parking goes. These form-based codes are taking over the country. You can build a building here tomorrow if it fits this shape based on this code. That's a great way to engineer a future that's much healthier, wealthier, walkable and livable.