This is the final story of a five-part series. Click here to read the other four parts.

Officer Adolfo Moriel tells his colleague to tilt his head toward the ceiling.

“I want you to close your eyes. Once you close your eyes I want you to think 30 seconds in your head. Once you think 30 seconds passed open your eyes and let me know,” Moriel said. “Do you understand the test?”

Moriel is a California Highway Patrol officer. He’s also a drug recognition expert, or DRE for short.

“Drug recognition experts have additional training in detecting and determining whether someone is under the influence of a specific drug,” he said.

On a recent morning, Moriel demonstrated how he’d evaluate someone who had been pulled over for driving under the influence. He conducts evaluations at the police station to determine what a driver may have consumed.

He says DREs study how the body reacts to alcohol and different kinds of drugs. Their evaluations include a number of physical tests.

“Drugs will make the eyelids flutter, so I’m going to take note of that if the person starts to sway,” said Moriel.

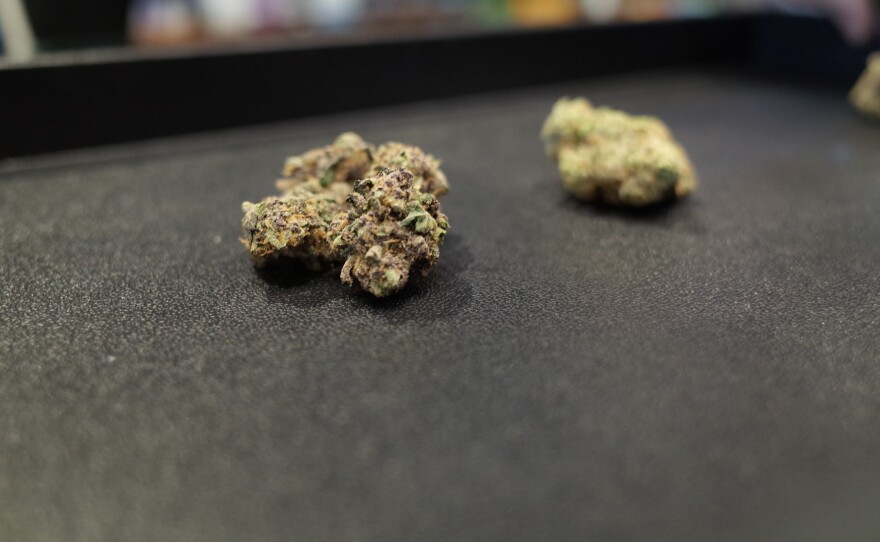

Marijuana is hard to police. THC — the compound in marijuana that gets people high — affects everyone differently. A small amount may significantly impair a novice user but not a chronic user. THC distributes throughout the entire body, which means it doesn't stay in the blood. So, traditional tools used on drunken drivers — like breathalyzers — don’t work.

And unlike alcohol, California doesn’t have a legal limit for drugged driving. So it’s up to Moriel and other DREs to decide whether someone is under the influence.

California law enforcement agencies are just starting to collect data on marijuana-impaired drivers, so it’s too early to tell whether recreational marijuana’s legalization in 2016 has contributed to reckless driving.

But Moriel says, he and his colleagues have seen a rise in vehicle crashes.

“Now that people smoke marijuana, they tend to smoke marijuana before they go to bed and immediately after they wake up,” Moriel said. “Now we are seeing DUI crashes … in the mornings. Before we didn’t have that.”

Moriel says California has about 1,400 DREs, but he thinks the state needs a lot more.

Marijuana is growing in popularity, but policing tactics are still unclear

At the Original Cannabis Cafe in West Hollywood, marijuana smoke fills the room as people eat their meals. Among the patrons is Ricardo Baca, a renowned independent marijuana journalist and the first marijuana editor for the Denver Post.

He says the cafe is an example of how far society has come with embracing marijuana.

“There is open consumption happening all around us. It just says we are finally entering an era of normalization,” Baca said.

Recreational marijuana was first legalized in Colorado in 2014. Five years later, law enforcement and governments are still figuring out how to regulate and police marijuana for safe consumption, he said.

“We are moving at a lightning pace,” Baca said. “Government doesn’t move fast, but the people have taken on this monumental issue [of pot legalization and decriminalization] and forced this change on the government, and it is trying to figure out what to do with it.”

In the meantime, Baca said relying on drug recognition experts’ opinions to determine whether someone is too stoned to be driving instead of a scientific tool can be unfair.

“They’re using roadside sobriety tests that were familiar from black-and-white movies,” he said. “It’s like touch your nose and that’s how they’re telling whether you’re high or not. There’s no scientific basis and that’s problematic.”

Scientific research catching up

That’s why San Diego researchers are looking at the science behind drugged driving. At the UC San Diego Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research, co-director Thomas Marcotte shows off a machine.

“It’s a completely interactive simulator with gas and brake pedals, steering wheel, crashes auditory sounds, etc ... it’s designed to mimic things in the real world,” Marcotte said.

Studies on drugged driving have been happening for a while. But, Marcotte said they have their limitations. For example, people often use different amounts of pot.

“Sometimes they look at just a couple of field sobriety tests may look at low doses they don’t always look at regular uses,“ Marcotte said. “So one of the things our study looks to do is if we take people who are regular users, the people most likely to go on the road … what would that look like on the road?”

The study also tests other tools that might tell if someone is too high, like a memory test on an iPad. One challenge with policing drugged driving is that scientists have long studied how people behave when they’re drunk, but not so much when they’re high, Marcotte said.

“The impression in most research is that with cannabis people tend to be more cautious and drive slower, he said. “So it’s a different kind of behavior you might see on the road, so how do you go about identifying those changes?”

Nearly 200 regular pot smokers have gone through the center’s driving simulation. Marcotte is excited to see what the data show but cautions that study will not be a catch-all solution for law enforcement.

“We haven’t looked at edibles, dabbing — where someone gets a big dose of THC all at once,” Marcotte said. “We can’t do that kind of research because those materials aren’t available from the federal government.”

Law enforcement, however, won’t be able to use any new technologies from this research until they are approved by the state, which can take time. And, research can take a lot of time too, especially with federal regulations on marijuana, Marcotte says.

“There are a lot of questions when it comes to public health and safety that researchers aren’t able to address."