One recent Saturday morning, about a hundred people sat on folding chairs in a hall at the First Christian Church in Downey. They were there for the church’s weekly food distribution.

Volunteers called out names from a list as people waited their turn to get in line for donated groceries.

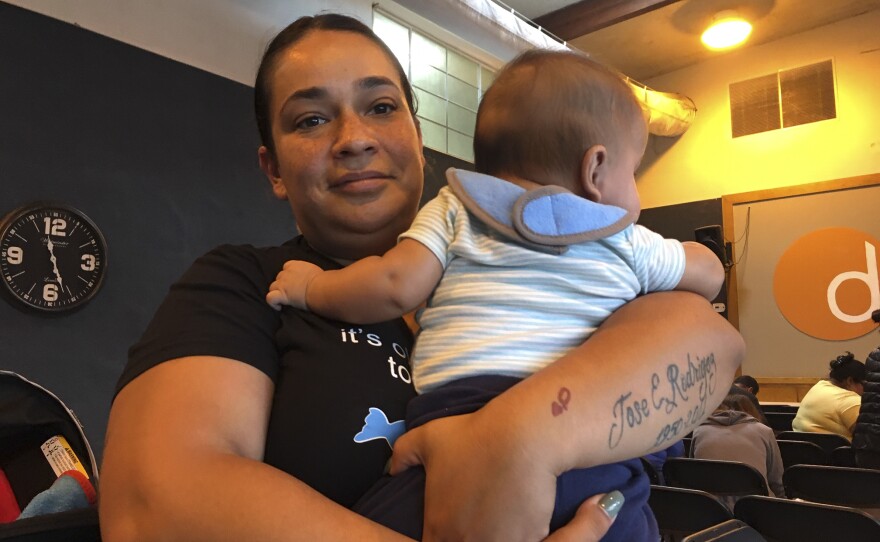

Among those waiting was Janette Perez. She sat in one row of chairs, holding her baby boy in her lap. Her 6-year-old-son played nearby. It was their first time here.

“I was told through my job that they were donating food here at the church, so I came by to see what they could give me, since we’re struggling right now,” Perez said.

Perez lives with her husband and two young children in South Gate, a short distance away. She and her husband both work. He installs car stereos. She works in nutrition at a Head Start preschool. But even with two incomes, she said, they’re just scraping by. It gets to her.

“It’s really difficult,” she said, tearing up. “Our rent is like $1,375, and our car payment is almost $500, so we can’t afford anything right now.”

RELATED: A Growing Latino Middle Class: One Family’s Journey From Have-Not To Have

Experts say that even as Latinos’ economic fortunes have risen in the U.S., with rising median incomes and the Latino poverty rate at an all-time low, according to census data, many families face a host of obstacles to upward mobility, especially as housing and living costs increase.

Unsteady work hours and a lack of access to banking and credit are among the issues that can get in the way. An education gap persists, despite rising high school graduation rates and college enrollment, according to experts. Filial duty and other family obligations can eat into finances. As for those who lack legal immigration status, opportunities have become increasingly limited.

And here, in California, the biggest challenge these days is the cost of housing.

Traditionally, saving up and buying property has been one of the main ways that Latino families have built wealth, said Jody Agius Vallejo, a University of Southern California sociologist.

But it’s harder to do these days. While the median household income for Latinos in the U.S. is now over $50,000 a year, it doesn’t get you much in California, she said.

“The high cost of housing in California is something that really threatens economic stability,” Vallejo said. “It’s not just the fact that home ownership costs are high. Even having to pay high rents can prevent people from saving to buy a home.”

The National Association of Hispanic Real Estate Professionals reported last year that Latinos in California have a lower rate of home ownership than in other states where Latinos represent more than 30 percent of the population. This includes states like Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, where Latino median household income is lower than it is in California. Housing affordability is a major factor.

Waiting her turn for groceries at the church, Perez said she and her husband wish they could buy a home, “so that my children have somewhere to live, so they won’t struggle the way we did,” she said. But it seems out of reach.

Perez said her mom, a first-generation immigrant from Mexico, owns her home, but she’s struggled to make the payments since Perez’s father died about six years ago, so she can’t offer much help.

Right now, Perez said, it’s impossible for them to save any money. Her job doesn’t pay over the summer, and her husband’s hours aren’t steady.

“The hours are not the same as they used to be,” Perez said of her husband’s job. “He will work maybe five days out of the week, sometimes four days out of the week.”

Unreliable hours are a problem for Latinos in lower-earning jobs, said Anthony Alvarez, an economic sociologist at Cal State Fullerton.

“We still do see high levels of what we would call income volatility, meaning that you have changes in your income, from week to week or month to month, or even year to year,” Alvarez said. “This oftentimes makes it very difficult to accumulate savings.”

While many groups are affected by income volatility, Latinos are among those hardest hit. A 2017 report from Pew Charitable Trusts found that Latinos and people with a high school diploma or less are the most likely to face income losses from unsteady earnings.

A lack of savings and emergency funds also makes it difficult for families to establish good credit, Alvarez said. Adding to this challenge is the fact that while banking rates for Latinos are gradually improving, according to federal data, many remain unbanked or under-banked. According to the federal FDIC, 14 percent of Latinos in 2017 did not use banking services. This is especially true among foreign-born, first-generation immigrants.

As for the second generation, extended-family obligations can be a drag on finances, such as when a parent or other family member needs money for unexpected medical costs or an emergency expense, Alvarez said.

“And that makes it more difficult for you to actually meet your own bills,” Alvarez said. “So the next thing you know, you’re late on your credit card bill, or your car loan.”

Also, for some, there’s a very big obstacle: legal status.

According to the Pew Research Center, the population of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. has declined substantially over the past decade or so, from an estimated peak of 12.2 million in 2007 to about 10.5 million in 2017. But recent policies have made it more difficult for people to adjust their immigration status.

At the church in Downey, food bank volunteer Catherine Alvarez said she’s sponsoring her husband for a green card.

“He’s undocumented, so it’s really difficult for him to get a job and stay there for the long term,” said Alvarez, a Downey resident who was born in Colombia and is a naturalized U.S. citizen. “As soon as they don’t need him, they just let him go.”

Alvarez says her family of four has struggled to stay as renters in Downey, a city that’s long been a draw for middle-class Latinos, with its quiet residential streets and well-regarded schools. They wanted to keep their two teen boys in school there. But in recent years she’s had health problems that have required surgery and kept her from working, she said.

Her husband takes all the work he can, from construction to odd jobs: “If he needs to clean a toilet, he’ll do it,” Alvarez said.

But at times it hasn’t been enough. About three years ago, when the family was hit with medical bills, they lost the apartment they were living in. They had to stay with friends and sometimes even in their car until they could raise enough to move into a new place, Alvarez said.

She’s hopeful that if her husband gets legal status, it could change their fortunes. But she worries: What if he’s denied?

“I get sad because I don’t know,” Alvarez said. “I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

With the pathways to middle-class status becoming rockier, will future generations of California’s Latino families have a harder time cracking the ceiling? Perhaps, said USC sociologist Vallejo.

“The California of today does not hold the same kinds of opportunities that it did 30 years ago,” Vallejo said.

But she added that there’s also reason for hope: The state has immigrant-friendly laws, she said, and has enacted recent policies like raising the minimum wage and expanding health care, widening the social safety net.

“If we can make education accessible for all, if we can...invest in things like access to capital and helping ease people’s housing burdens,” Vallejo said, “all of these things could really help to promote economic stability.”

Before she left to collect her donated groceries, Janette Perez mentioned that her mother-in-law lives in Arizona. It’s cheaper there, and the thought of moving has crossed her mind – often. But her mother and siblings are in the Los Angeles area, which makes her reluctant to leave. As they stick it out in California, Perez said she tries to appreciate what they have.

“I told my husband, you know what, at least we have somewhere to live,” Perez said. “There's a lot of people that don't even have a house. They have to live in someone's garage or like the homeless, that have to live in the street.”

They at least have jobs, she said, and a roof over their heads.

And they’re grateful for that.