Six southern white rhino females have called San Diego home since 2015.

The animals came here with high expectations. Researchers brought them to the San Diego Zoo’s Institute for Conservation Research specifically to help save their close cousin, the northern white rhino.

Only three of those animals are left alive, and none are capable of breeding, said Steve Metzler, a San Diego Zoo Animal Care Manager.

“They’re animals that have been here for millions of years. And we’re on the verge of seeing them disappear. After all of that longevity, we’re the reason they are starting to disappear,” Metzler said.

Poaching snuffed out the wild population of northern white rhinos and age is taking its toll on the survivors in captivity.

Metzler remembers the long airline flights nearly two years ago that brought these rhinos from South Africa. He first saw them just before they were crated up and flown across the Atlantic.

It has been quite a journey since then and Metzler remains impressed at how much they have taught researchers.

“We’re learning about training. We’re learning about techniques for the reproductive work that we need to do with them. We’re learning things to improve their health and well-being through the veterinarian team,” Metzler said.

Rhinos have already transformed since their arrival

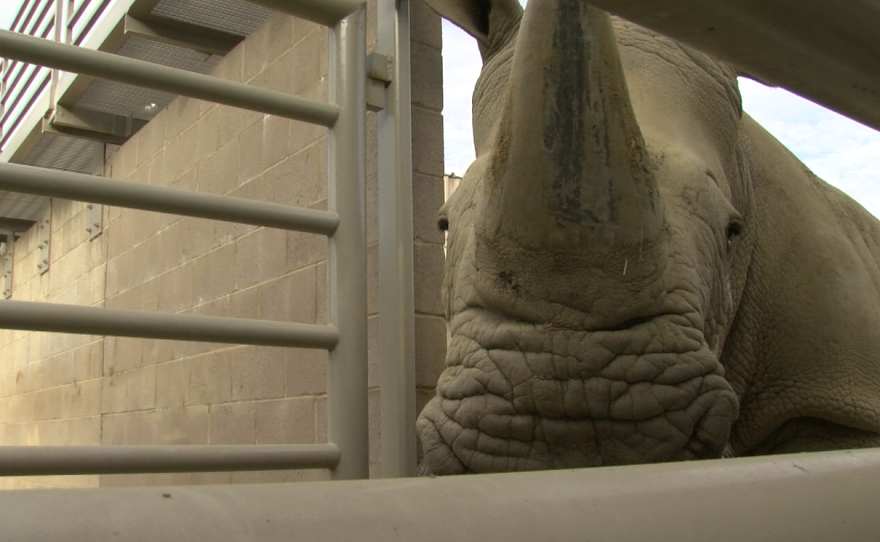

An off-exhibit area in the Nikita Kahn Rhino Rescue Center gives the six females room to roam and trainers up-close access. Keeper Marco Zeno took full advantage of the area encouraging the largest rhino, Amani, to come close.

RELATED: Endangered Northern White Rhino Dies In San Diego

“Give me your nose,” Zeno said.

The animal lumbers over to the trainer, enticed by the friendly words and a bucket of food treats.

“It’s remarkable that these animals that were essentially wild when they came in and after just about three months, we’re hand feeding and being really calm around people and have no reason to be afraid,” Zeno said.

Amani is the first of the six females to be inseminated artificially. If it works, researchers are taking a major step toward saving the northern white rhino species.

On this day, Zeno urged Amani to stand still while another keeper simulated a shot. This basic behavior gets the animals ready for the real thing.

Standing still for a shot pales in comparison to the once a week ultrasound researchers perform on the rhinos.

Ultrasound gives researchers an unprecedented view

Livia stands in the close-quarter chute of an examination area. A steady diet of snacks from keeper Jill Van Kempen keep the animal calm while researchers gather critical information.

RELATED: Rhinos Near Extinction As San Diego Researchers Look For Answers

But this ultrasound is not what you might expect. There is no application of cold jelly as a doctor manipulates the ultrasound wand on the outside of the belly. This wand is encased in plastic piping and it goes inside the animal.

“She’s being pretty perfect right there,” said Barbara Durrant, the director of Reproductive Sciences at the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research.

Post-doctoral researcher Parker Pennington manipulated the ultrasound wand while she and Durrant look at the images on the screen.

“We have two sets of females based on priorities. She (Livia) is once a week. And this is just to get baseline data. And then our other set of females get looked at, at least twice a week,” Pennington said.

The idea is to regularly check in on the animal’s reproductive organs. The researchers use the rectal cavity to get the device above the animal’s narrow and twisting reproductive tract.

RELATED: San Diego Zoo Gets Funding To Help Save Northern White Rhinos

“So, we go in with an ultrasound probe. And we look at the uterine horns,” Durrant said. “We look at the ovaries. And we look at the structures on the ovaries. And the structures we’re looking for are the follicles, which is the structure that holds the egg.”

Durrant is, in essence, writing the book on the rhino’s reproductive cycle because this research does not happen anywhere else in the world.

There is hope that what researchers learn will allow for an unprecedented successful artificial insemination with sperm from a southern white rhino.

“See this, that’s fluid in there, I’m going to take a picture,” Durrant tells Pennington as she sees a telltale clue for ovulation. There is fluid collecting where the eggs grow.

As the researchers strain to get the information they need, Livia calmly munches on treats. There is no sedation.

20 minutes after the exam started, the procedure is over and the animal heads back to its barn.

The future of the northern white rhino is in the balance

“So, what we’re trying to do with that information is not only just document what the estrus cycle of the rhinoceros is but we’re also trying to optimize our artificial insemination techniques, by doing the insemination when we know the time is exactly right,” Durrant said.

It will be a couple of months before researchers find out if the first attempt at insemination works. Amani underwent the initial procedure a few weeks ago.

Natural mating is not an option because researchers hope to develop and refine their artificial reproductive techniques. Durrant’s plan calls for all six rhinos to have successful births from the process. She wants proven success before she attempts to implant a more precious embryo.

“Everything we’re going through now is leading up to a female southern white rhino that can receive and gestate a northern white rhino embryo,” Durrant said.

That is possible because researchers have access to the genetic building blocks required to create a fertilized embryo.

“There are only three living northern white rhinos. But we have cell lines from 12. So, we have enough genetic diversity to raise a self-sustaining herd.”

Durrant’s challenge is to develop the timing and techniques necessary for a successful implantation.

Other researchers are figuring out how to unlock the Zoo’s genetic repository of northern white rhino cells. They are housed in the frozen zoo, nitrogen filled tanks that hold cells from thousands of animals.

Scientists hope to turn frozen tissue into pluripotent stem cells which are capable of becoming sperm and eggs. That combination could become a northern white embryo.

Solving both of those equations are required in order to give the northern white rhino a second chance.