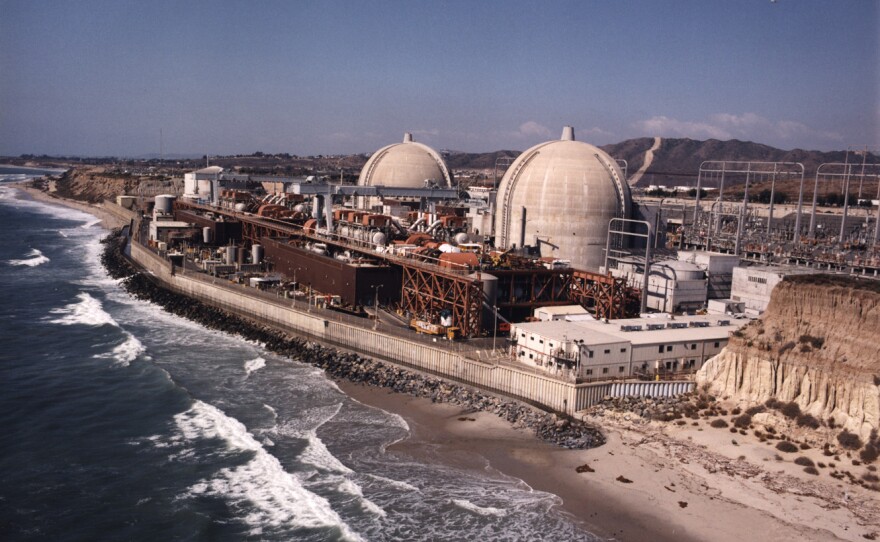

New seismic research from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography examines the earthquake and tsunami threats to the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station site, where nuclear waste will be stored indefinitely.

One of the report's principal researchers will present the results to Southern California Edison's Community Engagement Panel, which monitors the decommissioning of the nuclear power plant, on Thursday night.

San Onofre, or SONGS, was shut down in 2012 after a radioactive leak. But tons of radioactive spent fuel rods remain there, less than 60 miles north of downtown San Diego. Some fuel rods are already in dry cask storage, and many more will soon be moved from cooling pools into half-buried casks, 100 feet from the beach.

Neal Driscoll, a geologist with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and Graham Kent, of Nevada’s Seismological Laboratory, are the principal researchers in the study of the seismic threats to SONGS.

Southern California Edison, which owns the nuclear plant, originally asked the California Public Utilities Commission for $64 million for seismic studies in 2011, right after the disaster in Fukushima, Japan. But when San Onofre shut down, the studies were curtailed, and Scripps estimates this research, funded by ratepayers, cost $11 million.

Driscoll said the biggest earthquake threat to this area is not the San Andreas fault.

“The distance is about 56 miles,” he said. “So the San Andreas fault, you’d feel the shaking, but the ground motion is contingent on the material properties of the rock and the distance, so it doesn’t pose the serious threat to the people along the coastline.”

Newport-Inglewood/Rose Canyon Fault

Driscoll said the Newport-Inglewood/Rose Canyon Fault that runs in sections up the shoreline is a bigger risk for coastal southern Californians — and for SONGS.

“This fault, for people living along the shore, will cause greater ground motion because of its proximity, being eight kilometers at SONGS," he said. "But other places, it comes on shore and goes right through downtown San Diego, San Diego Bay.“

Driscoll pointed to maps that show a cross-hatching of lines offshore where his research crew took readings, recording the geology below the ocean floor.

“We spent 100 days of collecting geophysical and geological data offshore,” he said. “All of these lines show ship tracks that were collected with Scripps research ships.”

Though the Newport-Inglewood/Rose Canyon Fault is broken into sections, Driscoll concluded that the gaps between the sections are small enough that the fault could theoretically rupture from end to end.

“The maximum magnitude earthquake, if they ruptured end to end, is 7.3,” he said. “And if it ruptures the onshore northern segment, it could go as high as a magnitude 7.4.”

Officials with Southern California Edison, which owns the plant, said in 2011 when the plant was still operating, that the plant was built to withstand an earthquake of magnitude 7.

Edison now will only talk about design in terms of ground motion. The existing horizontal storage casks and the new vertical storage for radioactive spent fuel rods are both designed for a peak ground acceleration, or amount of shaking caused by an earthquake of 1.5 g. The cooling ponds, which will contain spent fuel rods until 2019, are less robust. They are designed for peak ground acceleration of .67g.

Oceanside Blind Thrust Fault

Previous data collected by oil companies showed another fault running right under the plant, a fault called the Oceanside Blind Thrust.

“One of the big questions was this,” Driscoll said. “If I had rupture on the Oceanside Blind Thrust — if it existed — could I trigger a rupture on the Newport-Inglewood/ Rose Canyon or vice versa? And that might release more energy having another fault system involved.”

Driscoll said his data — and older data that was reinterpreted — do not show evidence of the Oceanside Blind Thrust, so he believes that may be one less thing to worry about.

Tsunamis

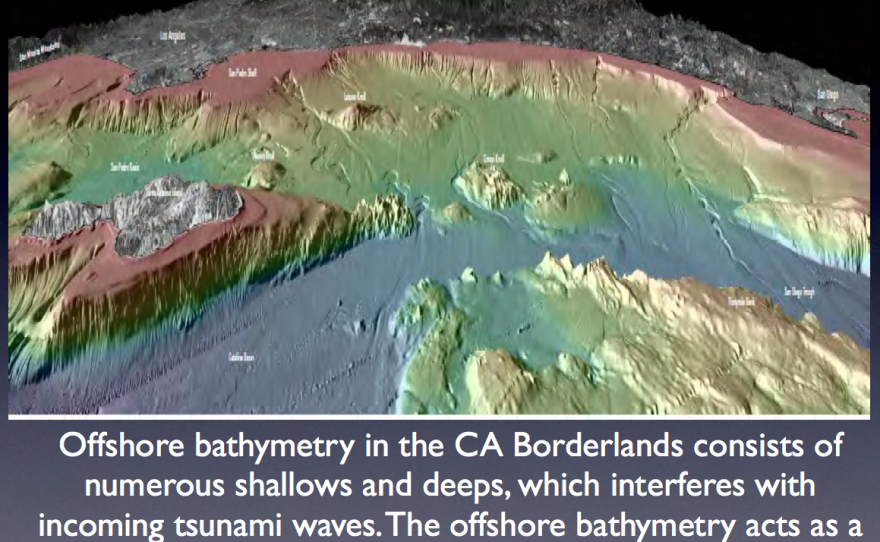

Driscoll said his data shows this part of the coastline is not as vulnerable to tsunamis as other parts of the West Coast. Pointing to maps of underwater peaks and canyons, he said the geology offshore would slow it down.

“What you’ll notice,” he said, “is that Southern California has this rough topography offshore here, shown here is in this chart — this rough topography — like Cortez Bank and Tanner Bank, they are shallows. The tsunamic energy comes in, and it builds up. But right adjacent it’s deep, and it collapses. So for ‘far-field’ tsunamis, the topography offshore — the underwater mountain ranges and valleys — acts as a natural baffle to tsunamis.”

Driscoll said tsunamis closer to shore could be started by earthquakes that cause underwater landslides. However, he has not found geological evidence of undersea landslides off this coastline.

Tsunamis have been measured as high as 130 feet, and the sea wall between the spent fuel storage at San Onofre and the beach is only about 30 feet high.

Driscoll’s office overlooks Scripps pier and the stretch of coastline that, he said, is rich with research possibilities.

“Our research shows that the risk or geo-hazard of the faults offshore when we first started this study are less than what we had predicted before.”

But he is not complacent.

“I find that the Rose Canyon, Newport-Inglewood system — which is right offshore here, in my office; I’m very close to it — it could rupture together. But the data we have offshore shows that the offshore segments have not ruptured in concert for the last 10,500 to about 13,000 years.”

The northern end of the fault ruptured as recently as 1933, and, Driscoll said, the last evidence of activity on the south end of the Rose Canyon fault was around the year 1650, give or take 120 years.

How all this actually affects the plan to store highly radioactive spent fuel at San Onofre is up to Edison to interpret, Driscoll said. Personally, he is not taking any chances.

“These bookshelves are all anchored to the wall,” he said. “Yes, everything in this office is very earthquake proof.“

Driscoll will present his findings Thursday night to Southern California Edison’s Community Engagement Panel. The meeting is slated for 5:30 p.m. at the Ocean Institute, 24200 Dana Point Harbor Drive, Dana Point.