Editor's note: We're following first-year special education teacher Elijah Gonzalez this school year. See the first part in this series here.

Watching Elijah Gonzalez in a classroom is a bit like watching a game of pinball.

The moment he's done huddling with one student, Mr. Gonzalez, or "Mr. G," as most students call him, bounces to the next.

Gonzalez is a special education teacher at Thrive Public Schools, but the students seeking his help don't all have special needs.

"Students on my caseload know (I teach special education), but as far as the other students, I think they're oblivious to it."

Gonzalez isn't trying to fool them. He teaches alongside other teachers at the charter school. Thrive is achieving what campuses throughout the county are moving toward: full inclusion of students with special needs in general education classrooms.

Federal law has long called for inclusion whenever possible. But during the 2014-15 school year, about a dozen districts throughout the county weren't meeting the state target of teaching 49.2 percent of students with special needs in general education classrooms for 80 percent or more of the day. And many districts were barely exceeding that.

Charter schools like Thrive are, by and large, leading the pack when it comes to inclusion.

What's working at Thrive

It's already common for schools to have specialists to help students with special needs succeed alongside their peers. What's different at Thrive is Gonzalez and his students aren't an appendage trying to keep up as the class marches on.

"For our students that are on what's called individualized education plans — so students that have special needs — they by law are mandated to have an individual plan, but at Thrive every kid has their personalized education plan," said Nicole Assisi, the school's chief executive officer.

"It blurs the boundary between needs," she said. "It makes every student be able to learn at their just-right level."

What that looks like in the classroom is a lot of independent work as students move through the curriculum at their own pace. Because of this, Gonzalez and his colleagues have to work like jazz performers, adapting as students stumble and excel.

"If I need to pull a group (out of class for extra help), I always make sure that I have one or two of my students on my caseload. And then more times than not, there's gen ed students who are struggling with the same topic, so we'll bring them in and do a quick mini lesson," Gonzalez said.

Just as it's hard to tell Gonzalez is a special education teacher, you can't really single out his students. Everyone at Thrive is getting specialized support.

"I call that mission accomplished," said Judy Mantle, dean of the Sanford College of Education at National University.

Mantle said the co-teaching model Thrive practices — where special and general education teachers work in tandem, each holding equal weight in the classroom and during lesson planning — is considered a best practice among educators and could become more common.

This year National is overhauling its credentialing program to give all prospective teachers more experience with special education so they can succeed in a co-teaching environment. Previously, Mantle said, teachers had one or two classes on special education if they weren't specializing in the field. Moving forward, it would be baked into nearly every class.

"Now we just bridge it into our curriculum," Mantle said. "It's part of what we do. You need to know as a teacher in California how to teach all children."

Various studies show students in classrooms with two teachers — including low-income students and those with special needs — are more likely than peers in single-teacher classrooms to test proficient in math and English.

At Thrive, students are in the 96th percentile for academic growth, meaning while all the students may not be at grade level, they're improving more quickly than the majority of their peers nationally.

Special education growing in charters

Parents may be noticing. Since opening three years ago, Thrive's special needs population has grown from 11 to 16 percent of the student body. In the county's largest district, San Diego Unified, the number of students with special needs has fallen 13 percent since 2010, according to state data.

Statewide, more and more parents of students with special needs are choosing charter schools. The proportion of students in California charters needing special education services now rivals that in district-managed schools — 9.2 percent compared to 10.4 percent.

The California Charter Schools Association says it's because successful charters are excelling at inclusion. Nearly 90 percent of students with special needs at charters are in general education classrooms for 80 percent or more of their day. That's compared with 53 percent across schools statewide.

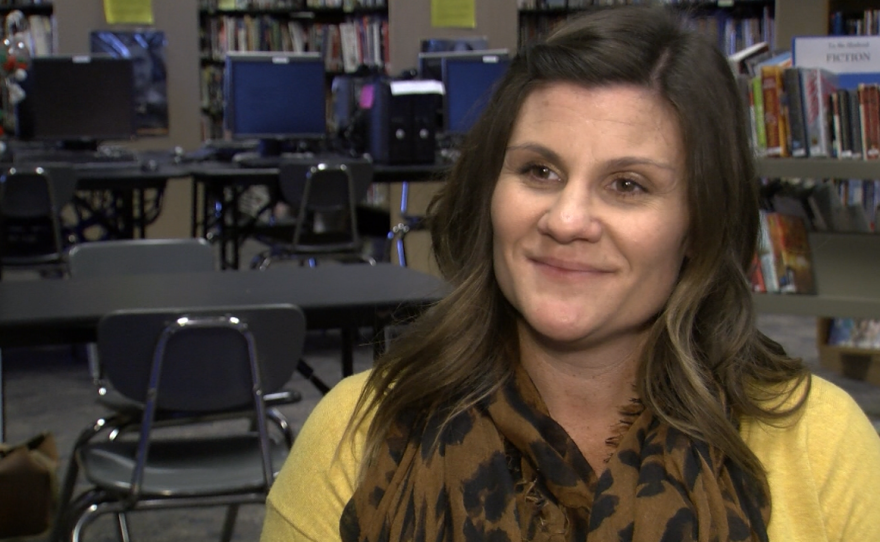

Jenny Moore, who heads special education at Guajome Park Academy, a charter school in Vista , said those numbers make a lot of sense.

"In larger districts, you can kind of think about it as they're trying to turn a ship, whereas, in the charter network we're maybe trying to turn a canoe," Moore said.

Full inclusion not an easy task

Moore and her colleagues this year are attempting to do what Gonzalez does at Thrive. She said the results are good — all kids seem to be improving — but it's not an easy task.

Co-teaching requires more time for planning lessons, and for building rapport.

"We've heard it described as a marriage," Moore said, "where it's two people coming together and bringing together their beliefs and their pedagogy and uniting it as one so that the kids get the best of both worlds but also have a cohesive classroom."

And part of building a successful co-teaching relationship can require a significant shift in mindset, said Mantle at National University.

"Those who have been prepared in the field of special education have what I will call a discipline identity. They have a great deal of pride around what they've achieved and they've accomplished in advocacy for students with disabilities," she said. "It is a bit of a threat to a discipline when we talk about changing it this way, but we need to deconstruct and then reconstruct a new way of thinking."

Mantle said it's up to credentialing programs to groom teachers who are used to collaborating.

That's perhaps one reason Gonzalez has succeeded at Thrive. Gonzalez is currently earning a credential through Teach for America. (He has an intern credential and is licensed to teach students with mild to moderate disabilities.) Collaborating with colleagues and other Corps members is all he knows.

The other big hurdle for co-teaching: it just might not work for some students.

"If you're in a classroom with 30 students and two teachers, that may be sensory overload for you and that might not be the best model for you," Moore said. "In special education, the needs of kids shift every year. It's never a dull day."

This could explain why larger districts seem less successful at merging special and general education. Districts have more students, including those with more severe disabilities.

The need for constant change is something Assisi at Thrive is well aware of.

"I think the staff here has done a really great job of looking at each kid and figuring out, like, 'OK, how do I help you? What can I do and how do we think outside the box?'" she said. "But even then, it's not one size fits all. It's trial and error and we're working hard — as I know other schools are — to figure out how do we meet kids needs today?"

When kids' education is at stake, that kind of trial and error may seem like a black mark. But educators say it's actually mark of a system nimble enough to change with its students.

Percent of students with special needs in general education settings 80 percent or more of the day in 2014-15

State target for 2014-15 was 49.2 percent

Alpine Union Elementary 64.5

Bonsal Unified 66.1

Borrego Springs Unified 80

Cajon Valley Union 46.6

Cardiff Elementary 88.1

Carlsbad Unified 65.9

Chula Vista City Elementary 60.3

Coronado Unified 55

Dehesa Elementary 90.9

Del Mar Union 75.2

Encinitas Union Elementary 73.3

Escondido Union Elementary 61.4

Escondido Union High 45.8

Fallbrook Union Elementary 52.3

Fallbrook Union High 24.8

Grossmont Union High 38.1

Jamul-Dulzura Union Elem. 48.8

Julian Union Elementary 86.1

Julian Union High 80

La Mesa-Spring Valley Elem. 55.8

Lakeside Union Elementary 60.5

Lemon Grove Elementary 46.6

Mountain Empire Unified 77.6

National Elementary 45.6

Oceanside City Unified 49.8

Poway Unified 50.9

Ramona City Unified 66.4

Rancho Santa Fe Elementary 81.5

San Diego Unified 61.5

San Diego Dieguito Union 51.9

San Marcos Unified 39.6

San Pasqual Elementary Union 90

San Pasqual Valley Unified 56.3

San Ysidro Elementary School 43

Santee Elementary 64.8

Solana Beach Elementary 69

South Bay Union Elementary 60.1

Spencer Valley Elementary 82.5

Sweetwater Union High 46.4

Vallecitos Elementary 87.5

Valley Center-Pauma Unified 45.2

Vista Unified 58.6

Warner Unified 74

Source: California Department of Education