Allison points to a tangle of red green and blue lines on her computer screen. Each is like a printout from a lie detector test. That is the brain going over and over again like what? I can't attach any meaning to it. She is an assistant professor in San Diego state research and sciences. She's studying brain responses to get a better picture of how they go from a new word to understanding what it means. For the past four years she's done it by putting kids neural activity and she teaches them made upwards. This has for -- 64 electrodes in it and it goes to the scalp. She uses something called an electroencephalogram or an EEG that is a take keep -- tightfitting cat that looks like something you'd see in a science fiction movie. It is dotted with little connectors. This is -- this assistant uses a syringe to inject the fluid. There is saline fluid that collects. They capture the brain activity on the computer so she can trace exactly what happens processes made upwards. Each sentence ends with a nonsense word. Nonsense words will represent one word and some will not. The two boys fought over the shop. They played catch with the shop in gym class I like to throw the shop. Does shop have a real word meeting Baltica You either button and going. I need a footstool for my gals. She drinks milk from a gallows. You bring the drinks and I'll bring the gas. Does it mean -- doesn't have meaning? The brain activity makes the messy lie detector like squiggle and in the first exercise when he hears the word shop it's a stand-in for a real word. The brain activity can actually see learning happening. It starts with a big dip on the line graph during that first sentence. That means Duncan is confused. His neurons aren't sure what he has just encountered. The second and third sentences and context. The dip gets shallower and shallower until it becomes a. The third time they hear the word it looks like the brain is processing it like it's a real word. This line means that they have actually learned. The brain is a responding to it the way it response to a known word. It's an analogy like the unknown word is the ball heading for a gap in the nuance are scrambling to field it. As the ball drops in the runaround's first the players know more about how it will unfold. It becomes streamlined and targeted. When they hear the nonsense that is working left side the third time that they hear the word there is less effort involved because there attaching meaning to the word. That is also when you hear something in conversation you were not expected. Even one of the subjects are not sure that they know with the nonsense word stands for she can tell by looking -- they can use the findings to develop strategies to reach the blue curvy line that signifies learning.

KPBS is exploring learning at the cellular level in a new education series called "What Learning Looks Like." The goal is to help us understand how learning happens — or should happen — in our everyday lives.

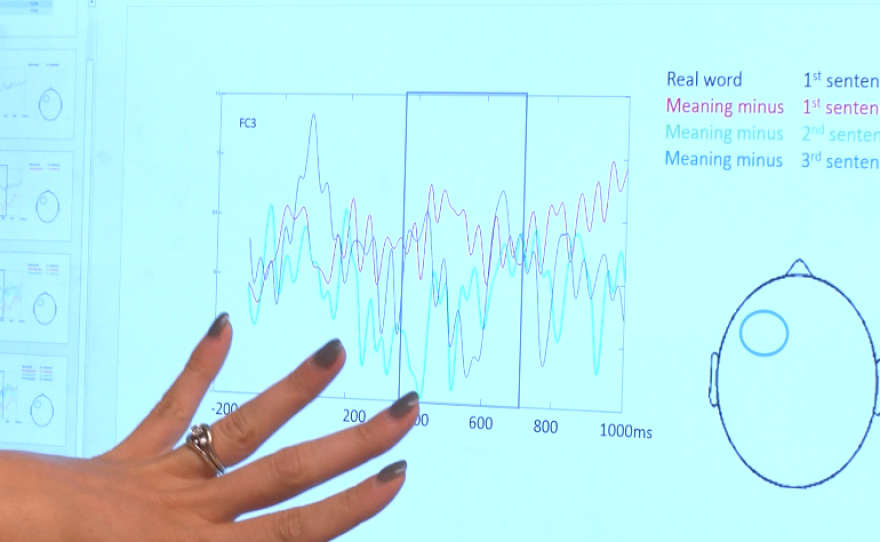

Alyson Abel points to a tangle of red, green and blue lines on a graph. Each is a bit like a printout from a lie detector test.

The squiggly lines mean her research subject was stumped — repeatedly — by sentences like these: "I need a footstool for my gouse. She drinks milk from a gouse. You bring the drinks and I'll bring the gouse."

Abel is an assistant professor in San Diego State University's School of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences. She runs a lab where she studies brain responses to get a better picture of how we go from hearing a new word to understanding what it means.

For the past four years, she's done that by plotting kids’ neural activity as she teaches them made-up words like gouse.

Abel recently simulated the study for KPBS on her colleague's 13-year-old son, Duncan Hawe.

"So you're going to hear sets of three sentences," Abel told Hawe. "Each sentence ends with a nonsense word, with a made-up word. Some nonsense words will represent a real word and some will not."

Duncan shook his head, which was covered with a tight electroencephalogram, or EEG, cap that sends electrical brain activity to Abel's computer. It looks like something out of a science fiction movie.

"Ready? The two boys fought over the shap," Abel read aloud. "They played catch with the shap. In gym class I like to throw the shap.

"Does shap have a real word meaning?"

Duncan got the answer right. Shap is a stand-in for "ball."

'I need a footstool for my gouse. She drinks milk from a gouse. You bring the drinks and I'll bring the gouse.' (04;48;56;14) 'In my room, I have a wooth. I like your shirt better than your wooth. I asked mom to get me a wooth.' Does wooth have meaning? No. (04;49;15;15) 'Her parents bought her a yadge. The sick child spent the day in his yadge. Mom piled the pillows on the yadge.' (04;49;33;13) 'He plans to repaint his nouch. I could hear them fighting through the nouch. When you leave, be sure to lock the nouch.' ((04;50;07;08) 'Mom spent time cleaning her rouch. He stood up on the rouch. The dinner is on the rouch.' (04;50;24;28) 'I was hungry so I took her thoose. The kids wanted to see the thoose. I am very allergic to the thoose.' (04;50;40;16) 'Before you get food, grab a naf. The cake was decorated with a naf. When I sit there I can see the naf. (04;50;58;20) 'The bird pooped on my tabe. My brother let me borrow his tabe. I like to drive my tabe.'

Abel has crafted more than 700 of these sentence sets so she can chart the progression in brain activity as children hear them. In this way, she can actually see learning happening.

It starts with a big dip on the line graph during the first sentence, "The boys fought over the shap." That dip means Duncan is confused — his neurons aren't sure what he’s just encountered. The second and third sentences add context. "They played catch with the shap. I like to throw the shap." The dip gets shallower and shallower until it becomes a peak on the line graph.

"So the third time they hear the nonsense word, it looks like their brain is processing it like it's a real word," Abel said. "The brain is responding to it the exact same way that the brain responds to a known word."

That response is called N400 and is well-known among cognitive scientists. It looks the same for every person regardless of age or IQ. What changes, depending on the person or setting, is how long it takes for the brain to have the response.

Abel likens what's going on in the brain during her exercise to a team of workers.

"So the first time there's a lot of work. The neurons are working really hard to figure out what this word is and how it's going to fit it into the sentence," Abel said. "And then the second time that they hear the nonsense word, the brain is working less hard because now it's heard the word and they've started to attach meaning to it. And then, in this case, the third time that they hear the word there is less effort involved because they've already been able to attach meaning to this word."

Another way to think about it is with a baseball analogy. The unknown word is a ball headed for the left center field gap. The neurons are players scrambling to field a triple. As the ball drops and the runner rounds first, the players know more about how the play will unfold. The team's efforts become streamlined and targeted.

Abel is hoping that by studying this process, she can help teachers and speech language pathologists develop teaching strategies to close the vocabulary gap. Researchers have estimated low-income children hear and learn some 30 million fewer words than more privileged kids by age three.

Abel is focusing on students in grades three and higher, because that's when the vocabulary gap widens.

"Most early vocabulary acquisition in school, teachers are giving out definition lists — word lists — to learn," Abel said. "Around third grade is when teachers flip-flop to teaching new vocabulary in this way where kids have to learn it through reading or listening only, and they can only use the surrounding language to help ascertain the meaning of the new word. So this relies heavily on their language abilities, it relies heavily on their reading in some cases, on their attention."

Abel and researchers at University of Texas at Dallas are currently looking at the differences in word learning among kids from low- and middle-income households. They have support from the National Science Foundation.

Abel, with support from a San Diego State grant, is also looking at word learning in children with language impairments but no cognitive or hearing impairments.

In both groups, the goal is to better understand what children need to go from a squiggly, confused line to a perfect N400 line more quickly.

"Is it that they need five sentences? Is it that they need three sentences with really strong support?" Abel said. "What's the best scenario for their learning to be successful?"