It has been nearly eight years since Bill Lockyer held elected office in California.

For more than four decades, he climbed the ranks of state politics — Assembly member, Senate leader, attorney general, treasurer — before ending a campaign for controller amid turmoil in his marriage and retiring at the start of 2015.

Nevertheless, Lockyer still has more than $1 million in a campaign account for the 2026 lieutenant governor race. Every month, he pays $2,500 to consultant Michelle Maravich, who said she helps maintain his donor list, manage meetings and appearances, and provide advice on occasional contributions to other candidates as the 81-year-old Democrat contemplates a comeback.

“He misses the public arena and obviously still wants to be of service,” Maravich said. “I haven’t seen him lose a step.”

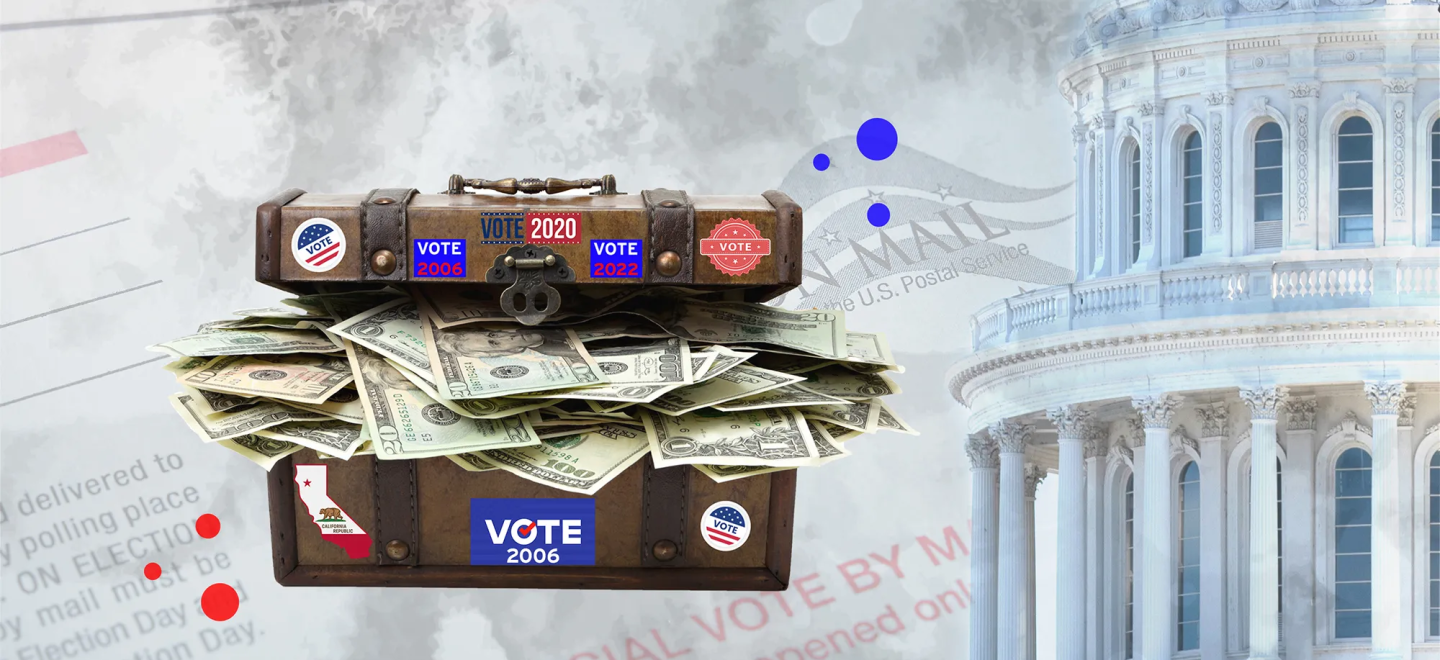

Lockyer’s seven-figure war chest is among the largest of nearly 100 accounts belonging to state political candidates with leftover campaign cash, according to a CalMatters analysis of California campaign finance records. Collectively, they hold about $35 million — funds that never got spent on the campaigns for which they were raised — ranging from $13.1 million that former Gov. Jerry Brown didn’t need to win re-election in 2014 to $9.62 in the account for a failed Assembly run that same year run by investment manager Thomas Krouse.

CalMatters counted campaign funds for the Legislature and state constitutional offices that politicians are sitting on years after leaving their positions, that are in committees for past races or for which the candidate did not end up running. These 96 accounts rarely raise new money, and in some cases, politicians have carried the same leftover contributions through election cycle after election cycle, transferring the money to new committees for positions they never actually sought.

The total does not include committees for candidates who ran in 2022. Those who lost in the June 7 primary have not yet had to file paperwork declaring what they did with any leftover campaign cash, while the deadline is still three months away for candidates who made it to the Nov. 8 general election to decide their next move.

Some of the politicians holding on to past campaign contributions are simply waiting to figure out their next race, at which point they may tap into those eligible funds. Others are using the money to keep a foothold in the public arena, slowly spending down what’s left on political donations, charitable contributions and administrative expenses. Many of the accounts hold massive debts and must remain open if the candidates ever plan to raise cash to pay off outstanding loans and bills. And some of the money is merely sitting idle, in accounts where nothing much goes in or out, save interest and annual state filing fees.

“Perhaps the lack of activity reflects my innate frugality,” said Mike Gatto, a Democrat who served in the Assembly from 2010 through 2016 and has almost $2.1 million in a lieutenant governor 2026 account, some of it from an abandoned campaign for state treasurer in 2018.

In the first half of 2022, the most recent period for which Gatto has filed a campaign finance report, he contributed about $2,500 to other candidates and earned nearly the same amount in interest.

Gatto said he typically raises money for candidates by turning to his donor list, rather than giving away his own leftover campaign cash, and he sits on the board of a family foundation that provides funding to charitable organizations. He is keeping his residual campaign funds for what he anticipates will be a return to politics in his retirement, after he finishes raising his three children.

“I hope there’s more in my future. I believe I can contribute to this beautiful state that we all call home,” said Gatto, who founded a law firm after leaving the Assembly. “I believe there’s a lot more freedom for people to run for office in their golden years.”

Avoiding surplus funds

Once a politician leaves office or loses an election, a regulatory countdown begins.

If a candidate wants to use any of the spare cash from a prior campaign to fund a future political venture, state law allows 90 days to set up a new account and transfer the money. Miss that window and the funds are designated “surplus.”

Surplus cash can be used to pay down debts, refund donors, expense administrative costs, support political parties or contribute to a “bona fide” charity. But it cannot fund a campaign for state office in California, whether the candidate’s own or someone else’s.

Avoiding that dreaded surplus designation is why so many former politicians always seem to be running for something — at least on paper.

The “dull” job of lieutenant governor, as Gov. Gavin Newsom once put it, is an especially popular choice. There are currently 21 open lieutenant governor committees for the 2026 primary, including for both Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins and Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon. Fewer than half are actively fundraising.

By passing cash from one account to another each election cycle, some former politicians can hang onto campaign contributions for years — even decades — after they held state office.

The 2026 treasurer campaign controlled by former Assembly Speaker Fabian Núñez, for example, is sitting on nearly $2 million. That’s what remains of the $2.1 million the account received from Núñez’s treasurer 2022 committee in late August. That account, in turn, got its cash from a Fabian Núñez for Treasurer 2018 committee, which was funded by a treasurer 2014 account, which was funded by a committee for a 2010 state Senate campaign.

This daisy chain of electoral accounts, connected by transfers made within those crucial 90 days after the end of each election cycle, reaches back to its ultimate source: the former speaker’s 2006 Assembly committee, which was shored up with a then-controversial influx of cash from the state Democratic Party.

Núñez has not campaigned for office since he was termed out of the Assembly in 2008. Through a colleague at the consulting and lobbying firm Actum, where he is a managing partner, Núnez agreed to an interview for this story, but never followed up.

He isn’t the only former elected official to play this game of financial hot potato. Besides Lockyer and Gatto, Jerome Horton, who served in the Assembly and on the Board of Equalization; former state Sen. Jean Fuller; Jeff Denham, who spent two terms in the Senate before he was elected to Congress; and others have all kept their electoral funds active by transferring the money from one account to the next.

Former Assemblymember Dario Frommer, who did not respond to multiple interview requests, still has $593,000 sitting in a committee for a 2026 controller campaign, all of it raised before he termed out of the Assembly in 2006.

Maintaining political influence

Former legislators hoarding leftover political funds may be an odd artifact of California law, but the rules are a significant improvement over the old days when politicians “were buying cars with the money, they were taking the money with them” upon retirement and they were using the money to expense “vacations that had nothing to do with legislation,” said Bob Stern, who served as the first general counsel to the California Fair Political Practices Commission, the state campaign finance regulator.

Throughout the 1980s, state lawmakers passed a series of gradual restrictions on what candidates could do with spare campaign cash. For the last two decades, spending has had to be plausibly tied to a “political or governmental purpose.”

So what counts as a legitimate purpose? Charities and political allies, for example.

In recent years, Núñez has used campaign funds to support the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, a nonprofit for which his son, Esteban, is a lobbyist, and After-School All-Stars, a charity founded by former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a personal friend who before leaving office commuted Esteban Núñez’s prison sentence for his role in a stabbing death.

Núnez campaign accounts have also poured six-figure sums into Proposition 1, the successful measure to add abortion rights to the California constitution, and a committee backing the unsuccessful mayoral campaign of Kevin de León, the former state senator and now scandal-laden Los Angeles city council member.

With $3.1 million in a lieutenant governor 2026 account, De León sits on the largest post-incumbency nest egg of any former state legislator.

He has doled out nearly $100,000 of that money over the last two years, mostly supporting political allies and causes. Top beneficiaries include an unsuccessful 2020 ballot measure to restore affirmative action in California, this year’s successful re-election campaign of Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara and the Los Angeles County Democratic Party.

De León’s most recent publicly reported contribution was a $25,000 payment filed on Election Day to the Santa Clara County Board of Education campaign of Magdalena Carrasco, his former romantic partner and the mother of his daughter. Carrasco lost her race.

De León initially responded to an interview request by text message, expressing incredulity about the amount of money reported in his account: “That’s all I have?” he said. “I must have some money missing.” He later said he was being facetious, though neither he nor his spokesperson replied to follow-up requests for an interview.

Electoral expenses are another legal way to distribute old campaign dollars.

Former Assemblymember Ian Calderon, who stepped down in 2020 to focus on his family, maintains a lieutenant governor 2026 committee from which he makes monthly $1,500 payments to a campaign consultant: his former chief of staff.

But the line that separates legitimate political purpose and personal expenditure can be blurry, especially for former politicians who have yet to show that they are actually running for the office listed on their campaign account.

“The harder part is when they go on a trip to Hawaii and attend an event,” Stern said. “If they’re not in office anymore, it’s kind of hard to justify.”

Not that some former lawmakers haven’t tried.

Shortly after Election Day this year, an account set up to fund a 2026 lieutenant governor campaign for former Assemblymember Autumn Burke reported spending $10,000 on a five-day trip to attend the Independent Voter Project conference in Maui with a guest. Burke left office last February to join a lobbying firm.

Neither Calderon nor Burke replied to emails and calls requesting comment.

Giving up on future campaigns

Politicians with no further plans to run for office — at least, not any time soon — can still avoid the surplus designation and retain more control over their leftover campaign funds by transferring them to a general purpose committee. Direct contributions to candidates are permitted from these accounts.

After finishing his second eight-year stint as governor in early 2019, Brown moved more than $14.7 million from his 2014 re-election campaign to the newly formed Committee for California. It has since spent $855,000 to defeat a 2020 initiative that would have rolled back a parole expansion pushed by the governor; donated $250,000 to the Oakland Military Institute, a charter school founded by Brown when he was the city’s mayor; and directed $141,000 into the most recent Oakland school board election.

“The primary focus is advancing the issues central to Gov. Brown’s gubernatorial terms, including but not limited to climate action, criminal justice reform and public safety, and education,” spokesperson Evan Westrup said in an email.

Westrup’s consulting firm, Sempervirent Strategies, is paid $10,000 per month by the Committee For California, its largest expenditure during the most recent two-year election cycle.

Lorena Gonzalez, who resigned from the Assembly in January to become the head of the California Labor Federation, used $1.1 million remaining in accounts for Assembly and secretary of state campaigns to form a new committee in May: The Future of Workers Action Fund.

Spokesperson Evan McLaughlin, in a text message, declined to provide further information on the goal of the account “beyond the obvious motivation reflected in the committee’s name and the reputation of its sponsor.”

A final, if rarely used option, for campaigns: Give back the unused cash to donors.

Across the accounts scrutinized by CalMatters, only a few reported significant refunds to contributors once a race was over, including former treasurer John Chiang, who returned more than $100,000 to supporters of his failed 2018 bid for governor — in December 2021, three and a half years after he lost. A representative for Chiang did not respond to emailed questions.

Former Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia, with his eye on higher office, had amassed hundreds of thousands of dollars in a lieutenant governor 2026 account by December 2021, when he launched a campaign for Congress. Over the next four months, he returned more than $170,000 in contributions to his supporters, alongside payments to his political consultants and donations to other candidates.

A spokesperson for Garcia, who will be sworn into Congress next month, did not respond to multiple interview requests. By November, after another $350 payment to the committee treasurer, his lieutenant governor account had just $73.76 left.

CalMatters data reporter Jeremia Kimelman contributed to this story.