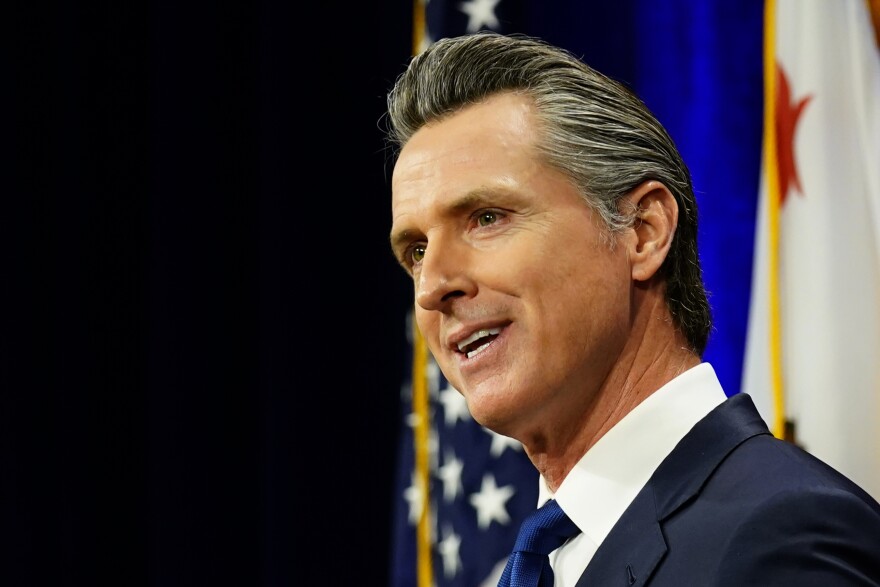

California Gov. Gavin Newsom delivered a mixed verdict on more than three dozen criminal justice laws before his bill-signing deadline Friday, approving measures to seal criminal records and free dying inmates but denying bids to restrict solitary confinement and boost inmates' wages.

Starting in July, one new law will give California what proponents call the nation’s most sweeping law to seal criminal records, though it excludes felons convicted of serious, violent and sex crimes. It will automatically seal conviction and arrest records for most ex-offenders who are not convicted of another felony for four years, as well as records of arrests that don’t bring convictions.

Backers estimate that 70 million Americans and eight million Californians are hindered by old criminal convictions or records. They estimated that the law could give more than a million Californians better access to jobs, housing and education.

Newsom also approved related measures, one allowing record sealing and expungement even if former offenders still owe restitution and other court debt, and another making it easier to apply for certificates of rehabilitation.

“Old records that no longer reflect the reality of who someone is and what they have accomplished should not be a barrier to opportunity," said Tinisch Hollins, executive director of Californians for Safety and Justice, which was among reform groups seeking the legislation.

The bills were opposed by law enforcement organizations that said they could imperil public safety and rehabilitation efforts.

Newsom also relaxed standards to allow more ill and dying inmates to be released from state prisons. The new law will allow inmates to be freed if they are permanently medically incapacitated, or have a serious and advanced illness “with an end-of-life trajectory,” the standard used by the federal prison system.

“It reduces incarceration costs, but more importantly, ensures there is a more humane and effective relief process for all people in California’s state prisons,” said Claudia Gonzalez of Root & Rebound, one of the reform groups that sought the measure.

Law enforcement opponents said the existing standards were adequate.

Among other new laws, Newsom approved requiring police agencies to screen prospective officers and fire current officers for participation in hate groups and allowed noncitizens to become police officers.

He also expanded a 2020 law that allowed suspects to allege that they were harmed by racial bias in their criminal charges, convictions or sentences. The earlier law was limited to cases after Jan. 1, 2021. But this measure extends the safeguards to prior convictions.

Newsom, a Democrat who says he supports second chances and reducing incarceration, has had a mixed record on criminal justice bills. He has backed many reform efforts but in years past also vetoed other legislation he felt went too far or duplicated existing efforts.

This year, he blocked a bill that would have made California the latest state to restrict segregated confinement in prisons and jails, as well as for the first time adding immigration detention facilities.

Newsom said he supports the concept, but the bill would have set standards “that are overly broad and exclusions that could risk the safety" of detainees and staff. He directed state prison officials to develop their own regulations to restrict isolation “except in limited situations, such as ... violence in the prison.”

He also vetoed one bill that would have given the state prison system five years to marginally boost the wages of inmates who usually earn just dollars a day, and a second bill that would have increased the “gate money" inmates are given upon their release from the current $200 to $1,300. The bills had survived even as lawmakers this year rejected a constitutional change that might have required much more compensation for inmate workers.

In both rejections, Newsom cited the unbudgeted cost of the bills as state revenues are slumping — a theme in many of his vetoes this year.