San Diegans just entered a multimillion dollar, long-term relationship with a bike lane expansion project in Balboa Park — one that has drawn hat tips from the cycling community while annoying motorists with traffic delays and construction.

But the headaches, even for non-cyclists, may be worth it.

With a price tag of more than $12 million, the Pershing Drive Bikeway is just one of 41 similar projects that make up a $200 million commitment to improving the connectivity and safety of San Diego’s roadways for cyclists. The projects were approved in 2013 by the San Diego Association of Governments, a regional transportation agency.

The project will expand existing bike lanes along a 2.3-mile stretch of Pershing Drive, a popular thoroughfare for commuters traveling north and south through the 1,200-acre park. It also will add a path for pedestrians, bike lane buffers and other traffic-calming measures meant to protect cyclists.

But also planned are improvements to another type of infrastructure officials say will benefit residents around the park, regardless of whether they’re bike enthusiasts: A portion of the cost of the project will go to replacing aging stormwater lines over the length of the Pershing Drive construction. Those upgrades will help prevent flooding and reduce water pollution.

Supporters say the bikeway project is much needed, especially following two fatalities of non-motorists on the stretch of Pershing Drive now under construction.

While riding a bike along Pershing Drive last July, 57-year-old Laura Shinn was struck from behind by a man suspected of driving under the influence. Then in September, 34-year-old John Sepulveda was riding an electric scooter in the bike lane along Pershing Drive when he was fatally struck by a car that drifted over.

Their deaths were among several inspiring members of the cycling community to rally for bike lane safety throughout the city.

Other residents around the park say while they support the safety upgrades, which will help the city meet its climate goals of reducing emissions from vehicle traffic, projects expanding bike lanes should be weighed against the challenges residents face with traffic and already scarce parking.

“There are some days where you are talking a commute that should take you 10 minutes is now taking you a half hour to 40,” said Carmen Cooley-Graham, who lives near the bikeway project.

Building a bikeway network

Commuters along Pershing Drive can expect delays and detours at least through the end of next year.

Funded by a voter-approved half-cent sales tax, the contract for the project was awarded in October to West Coast General Group, a Poway-based company. So far, $2.4 million of the $12 million budget has been spent, SANDAG spokesperson Stacy Garcia said. The budget also includes an additional $1.2 million to cover cost overruns.

Construction is slated to last until the end of 2023, but “given current supply chain constraints, there could be potential impacts to the anticipated construction timeline,” Garcia said, adding that concrete, for example, can be difficult to get when needed.

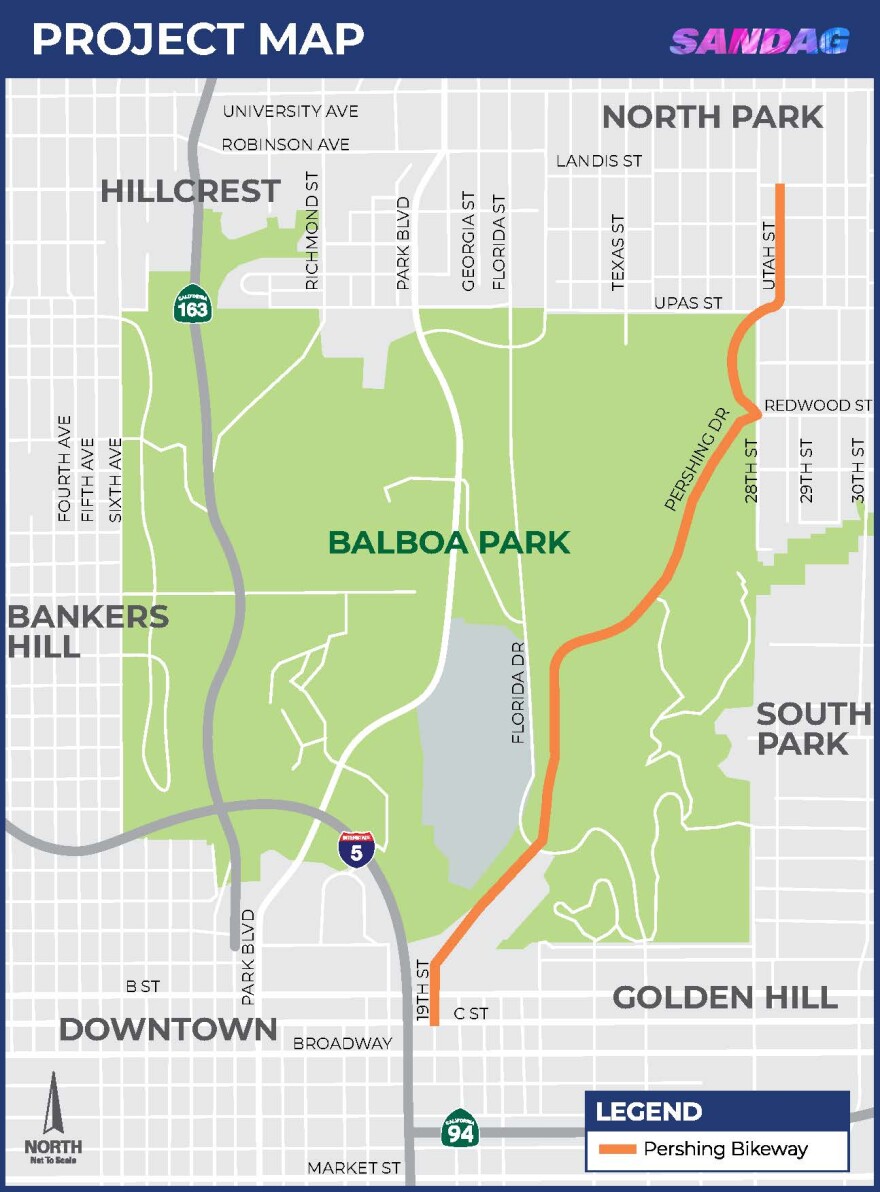

The bikeway will run along Pershing Drive from Upas Street north of the park to C Street south of the park. At the north end, the bikeway will connect to the recently completed Landis Bikeway at Upas and Utah streets and, at the south end, to the existing C Street cycle track at 19th Street.

Right now, motorists can only drive south on one open lane of Pershing Drive.

Along the same stretch of Pershing, the northbound vehicle travel lane is closed, and northbound traffic has been detoured along alternative routes, such as Florida Drive.

Currently, pedestrians and cyclists share a temporary two-way bike lane outside of the southbound road. That bike lane will be converted into one-way going south. Concrete barriers currently divide the existing bike lane and the road for safety purposes but will be removed once construction is complete.

Pershing Drive once was a four-lane road with one-way narrow bike lanes on both sides of the road. More than 14,000 vehicles were traveling the road in a day, based on the latest traffic counts, a steady increase over previous years. In preparation for the bikeway project, last year the city scrapped one southbound and one northbound lane citing it had “far less average daily traffic (ADT) than it was designed to handle,” according to officials.

Once construction is complete, Pershing Drive will have two north-south lanes for motor vehicles, a one-way southbound bike lane, and a two-way bike lane and sidewalk running along the northbound side of the road from B Street to Upas Street.

While the southbound bike lane will only have a painted buffer separating it from the road, a landscaped median with trees will divide the road from the two-way bike lane.

The project also includes a roundabout at Pershing Drive and Redwood Street, and a slightly smaller traffic circle at Redwood Street and 28th Street.

A flooding fix?

For residents around the park, the project comes with a non-cycling bonus update to a much more inconspicuous layer of infrastructure: the storm water system.

As California has experienced more extreme weather, residents and businesses in San Diego have dealt with flooding issues.

Flooding from heavy rainfall for some North Park residents has been so severe that it has damaged garages and other personal property. In 2019, water from a storm flooded basements and front yards and forced residents to shelter in place after a 30-inch pipe line burst.

The stormwater drains and filtration improvements along Pershing Drive, which make up nearly $2 million of the total cost of the project, should help homeowners and businesses in North Park and the Morley Field area with improved drainage, officials say.

Some of these improvements include installing bioswales —vegetation areas meant to capture, treat and filter stormwater — and replacing pipes and storm drains along the length of the project.

Improvements to an aging stormwater infrastructure should come as good news to local residents who want to see less flooding when it rains.

The existing stormwater infrastructure under and adjacent to Pershing Drive was installed in 1973, city of San Diego spokesperson Anthony Santacroce said in an email.

The bikeway project's stormwater upgrades will help prevent flooding, mitigate erosion and decrease water pollution surrounding the North Park and Morley Field areas, Santacroce said.

Bike lanes ‘polarizing’ in San Diego

The Pershing Bikeway project comes at a time when not all San Diego residents are on board with setting aside more asphalt for cyclists.

It’s going to take a long time for the public to move away from the “car-centric culture” that has dominated California for decades, said Jesse Ramirez, a community engagement coordinator for City Heights Community Development, a bike and transportation advocacy group in San Diego.

Bike lanes are “polarizing,” Ramirez said. While more bike lanes pave the way for greener transportation options, the public often sacrifices street parking or road width.

“It's either you're really for it or totally against it.”

In a separate bike lane project on Park Boulevard in the University Heights neighborhood, a group of protestors rallied at Park Boulevard and Madison Avenue in rebuke of the street’s new bike lane last month, arguing that the new lanes are logistically unfeasible and will deter customers from shopping at businesses on the street.

Long-time San Diego resident Antonina Sánchez, who lives near the Pershing Drive project, said there always has been a lot of traffic because of the park’s closeness to schools and other area attractions.

She said the bikeway, once complete, could lead to fewer cars in her neighborhood, which she would prefer.

“I think that would be the right thing,” said Sánchez, 46, in Spanish while walking her dog near Balboa Park one recent afternoon.

Cooley-Graham, who also runs a family museum in University Heights and enjoys biking and running, said Pershing Drive’s bikeway project is much needed because the existing lane was unsafe and “insane” for pedestrians and cyclists.

But government agencies should have spread out these construction projects because street or lane closures impact the city’s growing traffic congestion, she said.

Leaving two lanes open, for example, could have accommodated motorists better, she added.

“Once again, not against bike lanes,” Cooley-Graham said, “but not our whole community is gonna give up our cars in a day and jump on a bike.”