An uncle of Karen Christman, now a bioengineering professor at UC San Diego, had an artificial valve installed in his heart. But the first surgery didn’t go very well. And when the surgical team re-operated on his body to fix it they ran into a layer of scar tissue that they compared to a “wall of cement.” They couldn’t get access to the valve to fix it.

That’s what happens when the heart adheres to other tissue in the chest cavity.

Those kinds of heart adhesions are the reason why Christman co-founded Karios, a company that’s making a gel that can be sprayed on the heart to prevent it from sticking to other parts of the body, during and after surgery.

“It’s like spray paint, right?” said Gregory Grover, the CEO of Karios. “It sprays as a liquid but then it forms that shell. That’s exactly what our product does.”

Grover said when heart surgery first takes place, that exposure removes the heart’s protective barrier. And, in that state, it will very easily stick to other tissues in the chest cavity.

That adhesion doesn’t prevent the heart from functioning once the surgery’s over and the incisions are stitched up. But 20% of cardiac surgeries represent a re-operation, and that’s when the scar tissue can create a terrific obstacle, which can cause injury and sometimes death.

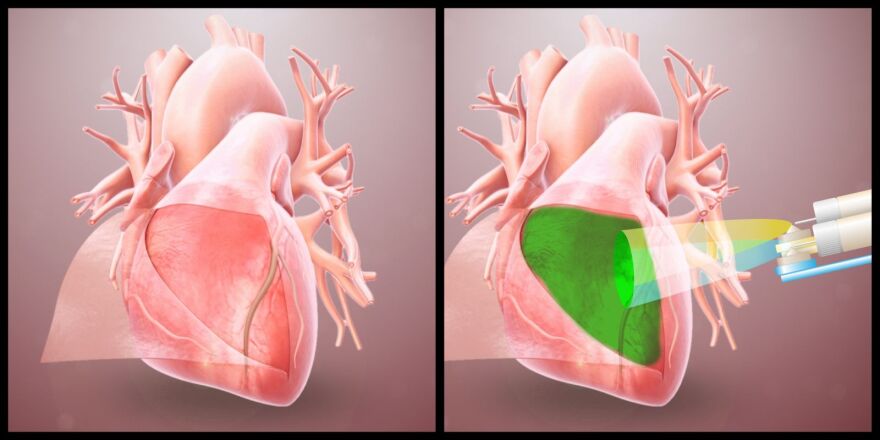

Christman said to prevent that, the hydrogel they’ve created would be applied to the heart once the initial surgery is complete. It coats the heart during the crucial time period that it takes the organ to heal.

“At the end of that first surgery, the surgeon would spray the material over the heart to create that protective layer,” said Christman. “So, a very thin protective layer that coats the heart, maybe one millimeter. It will degrade over time, but it will get the heart through that window of the first several weeks.”

Grover emphasizes the importance their product could play in preventing dangerous adhesions in kids who are born with congenital heart defects. Those kids, if they are to live into adulthood, must undergo three to six surgeries over the course of their lives.

The hydrogel made by Karios has been tested on rodents and pigs, according to the company founders. They say the next step is clinical trials on humans.

Although hydrogels are used to prepare for other kinds of repeat operations, none of them have FDA approval to use on the heart. Christman said one problem with many hydrogels is their tendency to cause swelling, which is a real problem in the tight cavity of the chest.

Grover, Karios CEO, hopes to market their hydrogel soon. If Karios can get permission from the Food and Drug Administration, they can start trying to prove it in human trials.