San Diego County probation officers have been disciplining youth offenders in violation of state regulations, locking them in their rooms for unnecessarily long periods of time, sometimes without any written justification.

Those violations were documented in a January report from the Board of State and Community Corrections, which found the San Diego County Probation Department was out of compliance with California regulations. In response, county officials have agreed to improve their practices and said corrective changes have already begun.

Under state rules, people housed in youth detention facilities can only be locked inside their rooms if they are a danger to themselves or others, and they should be released as soon as possible. The regulations follow a body of research that has found harmful long-term effects of confinement on children.

During a routine inspection late last year, state officials found that San Diego County probation officers “revert to room confinement for discipline instead of utilizing room confinement for the intended purpose, to ensure immediate safety and security.”

According to the state’s report, juveniles were automatically subjected to two hours of confinement for “inappropriate behavior,” a term inspectors could not find a clear definition for, and four hours for fighting. Youth did not have a chance to leave their rooms earlier, even if they no longer posed a threat.

Officials also pointed to an example where juveniles who were fighting were kept in their rooms for more than four hours without a documented reason, as required by state regulations. In another case, a young person was held for four hours and 59 minutes for unexplained “inappropriate behavior.”

“We take this issue seriously and our County is working with the Board of State and Community Corrections to make improvements,” said Nathan Fletcher, the chair of the San Diego County Board of Supervisors, in a statement.

“We are in the midst of reimagining Probation services so they are therapeutic and rehabilitative. Anytime you are improving your practices and culture, it is expected there will be some stumbling blocks, but we must do better,” he added.

A last resort

Room confinement, sometimes called solitary confinement, involves isolating an individual in a locked room and leaving them little to no ability to interact with others. In severe cases, some states allow juveniles to be confined for 22 hours a day or more.

The tactic can have severe consequences on children’s brain development and mental health. One study found that half of suicides in youth detention centers occurred while the juvenile was on room confinement. In response to growing evidence of harm, states have started developing new regulations, including a California law in 2016, to reduce the use of confinement in juvenile detention.

“Locking them in isolation in all likelihood would worsen whatever trauma or whatever triggers were the cause of the behavioral problems,” said Alan Mobley, an associate criminal justice professor at San Diego State University. “So it would be seen best as a very short-term solution to some immediate difficulty.”

Mobley directs San Diego State’s Project Rebound and the Center for Transformative Justice, which provide educational opportunities for current and formerly incarcerated youth. He said children in juvenile detention are often thought to be destined for failure, but when they are removed from punitive and traumatic environments, they have much better outcomes.

“It's not the case that they should be seen as a lost cause by any means,” Mobley said.

Inspection reports show San Diego probation officers resort to room confinement about 1,700 times each year. And since the beginning of 2021, there have been 56 confinements lasting more than four hours, according to the probation department.

In March, the county was required to submit a corrective action plan, which said officers were receiving briefings, trainings and memos about proper confinement procedures.

The county’s corrective plan said staff have less severe alternatives they can rely on, including restricting privileges like DVD players, asking youth to fill out worksheets about their behaviors and assigning them to community restoration projects.

Under the new plan, if a juvenile is sent to room confinement, an officer must mark down in a checklist that alternatives are not feasible and the tactic is not being used as retaliation or in any way that would “compromise the mental and physical health of the youth.”

The county also agreed to update its computer systems to distinguish safety threats from other “inappropriate behaviors” like damaging property or covering windows, which should not result in confinement.

Plus, in late February, the county started requiring supervisors to review all uses of confinement within one hour.

Chuck Westerheide, a county spokesperson, said the probation department is now in compliance with state regulations, and it is working closely with the California corrections bureau to “continue improving the environment for our youth.”

He added that confinement will still be used when necessary.

“While most room confinements are considerably shorter than four hours, it is reasonable to believe that youth will continue to be kept longer than four hours when it is in the best interest of the health and safety of youth and staff, and with the proper supporting documentation,” Westerheide said.

Juvenile justice overhaul

According to department policy, probation officers won’t release juveniles from confinement until they stop displaying “aggressive behaviors” like pacing, clenching their fists and banging on doors.

Sandy McBrayer, the CEO of The Children’s Initiative, said juveniles may display these kinds of behaviors if they’re distressed from being locked in their rooms. She emphasized the importance of having clinicians available to help.

“Are we sitting down and talking to the young person?” she asked. “Are we trying to do de-escalation?”

McBrayer said the state’s findings are concerning, but the county is working hard to address them. The probation department is partnering with the national Council of Juvenile Justice Administrators to help develop best practices.

“They’ve put a lot of things in place to say, ‘Let’s make sure we get on top of this,” McBrayer said.

Over the past five years, The Children’s Initiative has worked closely with county supervisors and the probation department to modernize juvenile detention in San Diego County.

The overhaul has involved demolishing old detention centers, including the Urban Camp and the Kearny Mesa Juvenile Detention Facility, and designing new facilities to replace them.

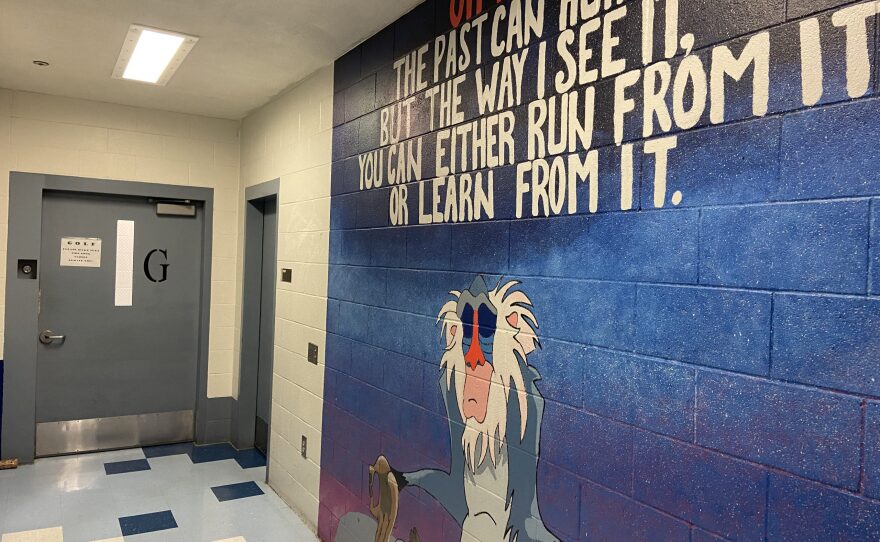

In January, the Youth Transition Campus officially opened, a project that used up $130 million from the county’s general fund. The facility houses young people who are found “true” — the Juvenile Court’s equivalent for “guilty” — and committed to out-of-home rehabilitation.

Residents, who can live on the grounds for a year or more at a time, have the support of on-site clinicians to help with distressing experiences and aggressive behavior. The campus is equipped with educational programs, a basketball court, a garden and an amphitheater.

“It’s important for San Diegans to know our County believes in the new direction Probation is headed, has dedicated significant resources to transform our facilities, and is committed to delivering trauma-informed care to the youth in our custody,” supervisor Fletcher said in his statement to inewsource.

A total of 150 people are currently held at youth detention centers across the county, including 65 at the new Youth Transition Campus.

A state law passed last year could boost that number as California phases out youth prisons, which have been lambasted for dangerous living conditions. About 50 juveniles from San Diego County currently living in these prisons will be released or relocated by mid-2023.

A myriad of concerns in East Mesa

The county Juvenile Justice Commission has found its own flaws with local youth detention centers.

For years, the commission has asked officers to limit, and eventually eliminate, the use of pepper spray on juveniles.

“The Juvenile Justice Commission strongly encourages and recommends the Probation Department review, evaluate, and implement changes to (pepper spray) use and de-escalation tactic practices to ensure the safety of youth and staff,” the commission wrote in a 2018 report.

Yet pepper spray was still used in 2020, the most recent year of data available — a total of 94 times across all facilities.

And when inspectors reviewed the East Mesa youth detention center in 2021, they compiled a list of other concerns: There was only one nurse working in the evening when two or more were needed, the facility didn’t have clerical staff to help document illnesses or treatments and the department had removed “crash carts” that held necessary medical equipment, leaving staff scrambling to find and carry the right tools during emergencies.

Plus, inspectors noted, the East Mesa facility had no way to track juveniles after their release, staff morale was low and executives offered little transparency to employees about their decisions.

Currently, the East Mesa Juvenile Detention Center in Otay Mesa is the only facility holding juveniles as they go through court proceedings, a process that can take a few days or months. The facility had a $21 million budget in 2020.

“If you go into our East Mesa facility, which was built during the ‘superpredator’ time, you would think you're at Donovan State Prison,” McBrayer said, referring to a period in the 1990s when the federal and state governments instituted harsh criminal justice policies.

“That’s not conducive to a therapeutic, rehabilitative facility,” she said.

The county is now in Phase II of its juvenile justice overhaul: building a new, modernized youth intake center in Kearny Mesa that will reduce reliance on the old East Mesa facility.

McBrayer said The Children’s Institute will soon be giving the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors a tour of San Diego’s new programs as the officials begin reimagining their own juvenile justice programs.

“We really built something that’s going to be a model for the nation,” McBrayer said. “If we run it the way it was built, for the intended purpose.”