Located on the busy intersection of Imperial Avenue and 27th Street in Logan Heights, a small terracotta and blue party store sells piñatas and candies.

It's called Las Delicias, and it’s one of several party stores that line Imperial Avenue. But there’s something special about Las Delicias that few people remember.

The building is a significant landmark for San Diego’s Black community. Long before it was a party store, it’s where the Baynard Photo Studio operated for more than 40 years.

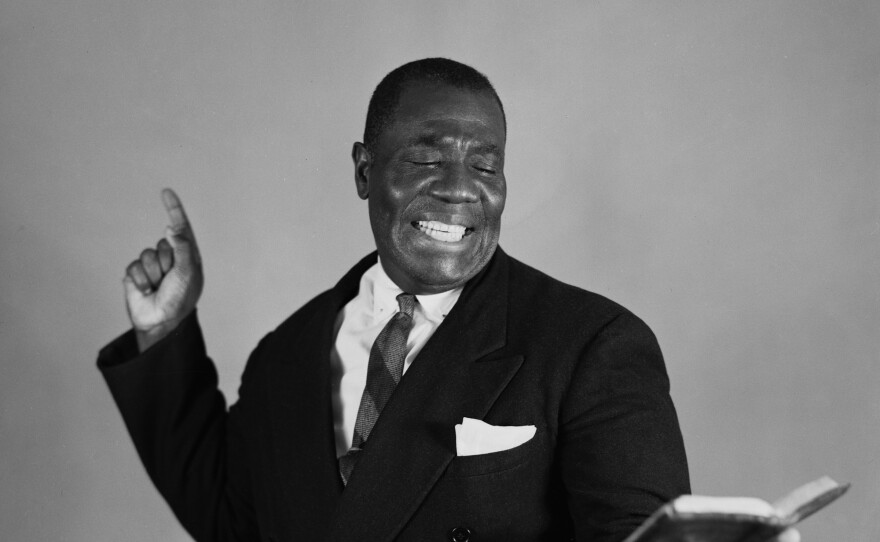

Norman Baynard, a self-taught photographer, ran the studio, and through his work created an unintentional portrait of Black life in San Diego from the early 1930s up until shortly before his death in 1986. A devout Muslim, he later changed his name to Mansour Abdullah in 1976.

Over the course of his life, he took nearly 30,000 photographs, all of which are now archived at the San Diego History Center. It’s one of the largest photographic archives of Black life west of the Mississippi River.

“What he did, whether intentionally or not, was to capture the 3D-ness of Black San Diego,” said Shelby Gordon, the marketing manager at the San Diego History Center. “The faces, the emotion, the victories, the struggle, the dimension, the broad range of colors and sectors and classes.”

Baynard migrated to San Diego from Michigan in the early 1920s, and after some stints playing banjo at night club and gardening in Mission Hills, finally found his passion in still photography.

His son, Arnold, donated the photo collection to the History Center. He recalled in an interview for the history center’s podcast how his father, who was also colorblind, built the business up in spite of the obstacles.

“He learned it all through experiment and trial and error and from that it just took off from there,” Arnold Baynard said.

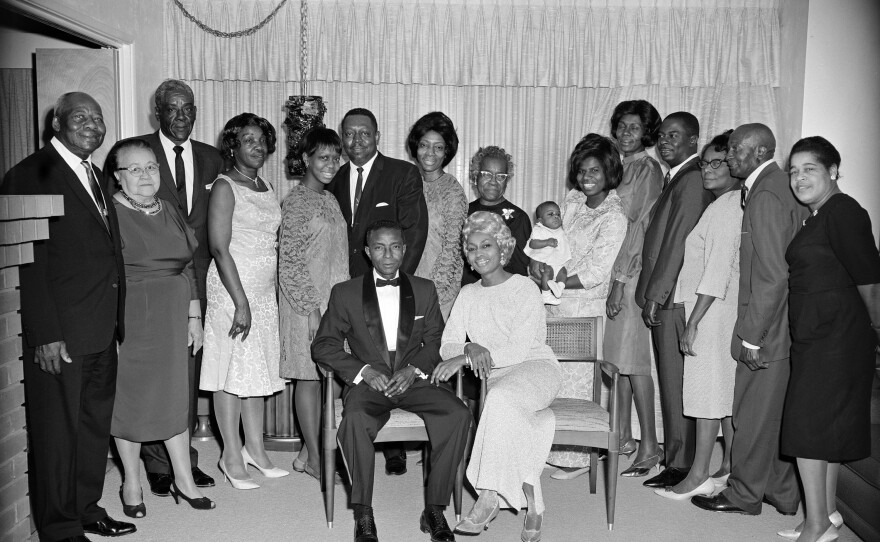

The photos show childhood birthday parties, like one taken on Janette Bowser’s sixth birthday party in 1950. In it, Bowser and all her friends pose in white dresses.

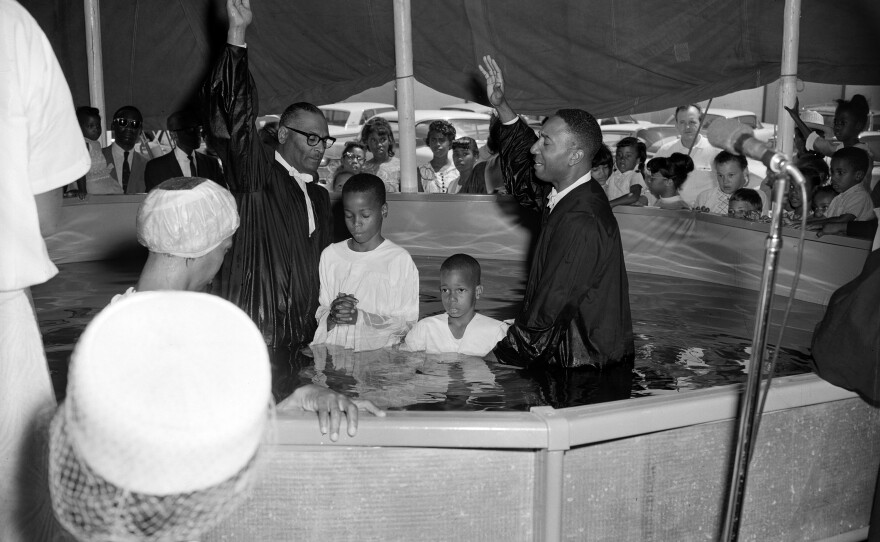

They also show baptisms, like one hosted by the 31st Street Seventh Day Adventist Church under the so-called “big tent,” which shows two young boys being baptized in a big pool. Baynard captured the quotidian moments of life.

“History is personal. It's about individuals collectively,” said Gordon. She urges people to celebrate Black life during Black History Month, not just the well-known leaders.

Baynard’s photos are a testament to the fact that history is told through the lives of powerful people but made by everyday people, she said. They show snapshots of ordinary Black lives lived and enjoyed, despite the struggles.

Of the thousands of photographs at the center, 500 have been made available online. And in 2011, community members poured through the archives, ultimately identifying hundreds of people and places captured in the photographs.

One person identified was Essie Smart, who won “Colored Woman of the Year” in 1957, an award presented by the local Black paper The Lighthouse.

Community members also identified places that don’t exist anymore, like the RBG House of Music, which was located on Market Street right across from the Mt. Hope community garden. Now that building is vacant and shuttered. Baynard’s photographs are the last remnants of a place that once drew crowds.

In this way, the photos help connect the past with the present. This is more vital than ever when the teaching of Black history is being challenged in schools across the country, Gordon said.

“We are still having some of these struggles and the hope and the desperation and the intention and the commitment that you may have seen in the 50s, 60s and 70s, it establishes a bridge,” she said.

The Baynard Collection ends in the 1980s, which leaves the History Center with a large gap in its collection and a big question: who is building the future archive of Black life in San Diego today?

“I think the key for archiving Black history is reaching into the communities for them to tell their personal story,” said Gordon. “Tell us your story, submit your leader, tell us what our timeline is missing.”

RELATED: Artwork from the Black Lives Matter memorial has a new home: the Library of Congress

The History Center is already collaborating with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture to document and preserve the Black Lives Matter movement and has created an online portal for Black San Diegans to contribute photos and complete the archive.

The future archive will likely be largely online and less portrait-driven like the Baynard collection was, given the decline of photo studios and the advent of smartphones and social media, but Gordon said that’s a good thing.

"What I really want people to do is to capture their family event at Mission Bay Park, post it on Instagram and then upload it on our site,” she said. “Because everybody has a phone in their hand now and we take tons of photos, so that’s what’s going to save us.”

It means there will be more content and perspectives to consider and learn from, but she urges people to save their photos and think about contributing them to the History Center’s archives. Because in the future, the moments of today will become bridges to the past.