Eighteen miles south of the Central Valley home that was her prison, down Highway 99 past almond orchards and trucks overloaded with hay bales, sits the Madera County Superior Court. The four-story steel structure with its light granite exterior boasts 10 courtrooms, large flat-screen monitors and a glass-skinned atrium. The courthouse opened in 2015 in this county of 160,000, part of a decades-long effort to shift funding and oversight of local courts to the state and ensure equal access to justice for all Californians.

“The Madera Courthouse was designed to demonstrate the transparency and dignity of democracy, providing a place to facilitate the workings of the American ideals of justice,” the architect’s website says.

Calley Garay, a 32-year-old mother of three young boys, came here in June 2020 seeking protection against a husband she said was abusive.

Julio Garay warned her that a restraining order was nothing more than a piece of paper and wouldn’t keep him away, court records say.

But the beatings were getting worse, the threats more ominous, and local law enforcement was still investigating her allegations. She needed help. So, planning for a new life with her children free from his control, Calley filled out the standard domestic violence restraining order request. Hers was one of 72,000 such forms Californians — mostly women — filed statewide that fiscal year, including 211 in Madera County.

We are now married or registered domestic partners. Check.

We are the parents together of a child or children under 18. Check.

I believe the person…owns or possesses guns, firearms, or ammunition. Check.

The answer to that last question on Calley’s form told the court her case could be particularly dangerous. Research shows the presence of a firearm increases the likelihood domestic violence will turn deadly. It’s why people who are the subject of a restraining order in California — even a temporary one — aren’t allowed to have guns. By law, they are supposed to surrender their weapons to law enforcement or a licensed dealer within 24 hours of being served.

And if a simple check box wasn’t enough to grab a judge’s attention, Calley attached to the form more than a dozen pages of horror, including descriptions of assaults and photos of bruises on her leg, back and chest.

Through it all was mention of a gun — a gun in his pocket when he yelled at her outside their son’s school. A gun when he threatened to take her into the orchards and kill her.

'He has always told me that a restraining order is not bulletproof and that he will find me.' — Calley Garay, in court documents

What happened to Calley Garay — a story that culminated in the Madera courthouse last November — is about more than one woman. It’s about California’s inability to disarm abusers, a longstanding failure that judges, advocates and law enforcement have been warning about for years.

CalMatters spent months combing through government reports, reviewing case files in various counties, and interviewing people across the state. The reporting shows that equal access to justice is still elusive. The protections domestic abuse survivors get from the courts vary widely, depending on where they live or the judge handling their case.

And California, with arguably the toughest gun control measures in the country, too often struggles to enforce those laws.

In July, CalMatters reported on the state Justice Department’s difficulty clearing a backlog of cases in its Armed and Prohibited Persons System, a database of known gun owners who are barred from having firearms because of a conviction or other court order. At the start of last year, 24,000 people were in the system, including nearly 4,600 because of a restraining order. Those are just the people California knows have guns. It doesn’t include the many people — like Julio Garay — whom abuse survivors say possess unregistered firearms.

In her request for a restraining order, Calley ended her description of a May 7, 2020, attack — the one that drove her to leave — by telling the court about fear.

“He has always told me that a restraining order is not bulletproof and that he will find me,” she wrote.

A month later, he did.

I

Calley Jean Garay realized she had to escape in May of 2020. Everything was getting worse.

The beatings were frequent and with whatever was at hand: June 2019, a belt. August 2019, a steel-toe boot. November 2019, a screwdriver. February 2020, a fire poker. May 2020, a black metal bar. In one attack, her 6-foot, 260-pound husband hit her so hard with a hair brush that it broke and flew behind her dresser.

CalMatters pieced together Calley’s story through interviews, state and federal court filings and sworn testimony. An attorney for Julio Garay said his client wouldn’t talk for this article.

Records show that almost anything could set him off. A misplaced receipt, coffee that was too hot, a truck that wouldn’t start. The first time he hit her — punching her glasses off her face while sitting in a Taco Bell drive-thru in December 2012, shortly after they'd started dating — was after arguing on the phone with his prior wife. Another time he beat Calley because some men had cheated him in a car deal and Julio blamed her for not having his back.

Calley said he had a signal when he felt she was disobeying him and a beating was coming. He’d start tapping his foot on the ground.

If she stayed, there was only one way it was going to end.

“She was terrified that she was going to die if she didn’t get out of there and her kids were going to be killed as well,” said Sarah Rodriguez, 37, Calley’s cousin, who grew up with her in Chowchilla, a city of 18,000.

Rodriguez’s mother, Terry Bassett, lived near the Garays in the quiet neighborhood of well-kept single-family homes. Bassett’s son was in the front yard in early May of 2020 when Calley — who might have lived a world away for how little she saw of the family by then — made a quick U-turn in front of him and told him to have her aunt come by to talk, Rodriguez said.

That conversation kicked off a flurry of calls and activity in Calley’s large family. They were getting their girl back, but she needed help.

Rodriguez said she and her mother rented a black Toyota SUV out of town and parked it away from the house. They reached out to a local victim services organization, which helped arrange for a hotel room for Calley and the boys, then ages 1, 4, and nearly 6.

The day of the escape would be May 15, 2020, when Julio, a truck driver for Save Mart, was working in Monterey. There would be a window between 3 a.m. and 5 a.m. when he wouldn’t be checking in by phone to make sure she was home.

Bassett stood by the front window in the dark early morning, waiting to see Calley come out of the house. But the time began to tick away: 4 a.m. ... 5 a.m. ... 5:30 a.m.

Bassett was in constant contact with Rodriguez. They wondered if they should knock on the door. But what if he’d come back?

Calley had tried to escape once before in 2015, the year the couple married. She went to the Chowchilla police and had criminal domestic violence charges filed against him. She also sought a restraining order from the family court in Madera, alleging he threatened to shoot her head “clean off.” But she had a 1-year-old son and was pregnant with a second, and gave up on the restraining order, records show. Calley’s family believes he found out where she was hiding and forced her home.

Julio took a plea deal in the criminal case. The same day in 2016 that she was in a Fresno hospital giving birth, he was in a Madera courtroom pleading no contest to disturbing the peace “by loud and unreasonable noise.” He got off without jail time.

At 6 a.m. on May 15, 2020, Calley finally emerged from the house. It turned out, she had forgotten to pack Julio chips in his lunch and he’d called to yell at her, telling her he was going to put her in the morgue, Rodriguez said.

The aunt rushed over, and they loaded the three sleepy boys into the rented SUV and drove straight to the Chowchilla police station.

Officer Ernest Escalera took the report. Over the course of an hour, she told him about the assaults and how Julio had warned that a restraining order wasn’t bulletproof, he would later testify.

“She was crying and stated that he was going to try and kill her,” Escalera said. They did the interview in the lobby of the station because of COVID and Calley seemed distracted — watching the passing cars and saying she expected to see him. A female sergeant took photos of the bruises over Calley’s body.

The family then drove Calley and the children to the hotel.

Threats. Beatings. Escape plans. Secret hotel rooms

This is the reality for domestic violence survivors every day across California. Many, like Calley, connect with a local nonprofit to help navigate the justice system.

In Sacramento County, these survivors end up on the third floor of a modern office building, at the Sacramento Regional Family Justice Center. Like the victim services organization that helped Calley, this is where police and prosecutors in the capital city often refer abuse survivors for everything from counseling and shelter to filling out court forms and legal advice. The center is conveniently located above the county’s child support services and across the street from family court.

Some people end up here on their own. In fact, many women and men experiencing abuse choose not to involve law enforcement for a variety of reasons, experts say, including fear of police, concern about the impact on child support, and the risk of further antagonizing a dangerous partner. Instead, they might seek only protection via a family court-issued domestic violence restraining order. That means a family court judge might be the only official to ask about a gun and try to ensure an abuser is disarmed.

On a recent morning at the Sacramento office, a handful of women sat in a waiting room for their turn to speak with a counselor or attorney. Inside, others were in private rooms — named after domestic violence homicide victims — sharing their tales of abuse and getting help filling out a state form called a DV-100, the court system’s restraining order request form. A golden Labradoodle named Buddy wandered the office, trained to nuzzle up to those in emotional distress.

The office sees as many as three dozen people each day, mostly women. Hanging from the ceiling in one wing of the suite are stuffed sea creatures that a detective brought in, a cheerful addition for the kids who often accompany the abuse survivors and who sometimes must share their own stories in special interview rooms.

The center’s case managers and attorneys always ask new clients whether their abuser has guns and to make sure to include that information on restraining order request forms, said Faith Whitmore, the center’s chief executive officer.

But, she said, judges there don’t seem to follow up — failing to ask detailed questions or use their power to try to force abusers to comply. Among those powers: Family courts are empowered to hold hearings to check on the status of guns, and judges can hold abusers in contempt if a firearm isn’t surrendered.

Whitmore acknowledged it can be difficult for courts to know whether an abuser is actually armed. Many guns are unregistered, invisible in a background check. And sometimes victims believe there’s a gun but lack proof.

Still, the stakes are so high the courts should be trying harder — asking questions, holding hearings, checking for receipts, she said.

“If it is the law — and there’s a reason there is a law and the courts are the ones to enforce that — it seems that throwing up one’s hands should not be the default response,” Whitmore said.

Social worker Yolanda Torres sat in on two recent cases in which victims alleged their abusers were armed. In one case, the gun was surrendered, Torres said. In the other, the abuser claimed to have sold the gun but “there was no follow-through,” she said — the court simply took the man’s word and moved on.

'We haven’t seen any kind of proactive approach from the courts to ensure that the individual has relinquished their guns.' — Ayano Wolff, attorney, Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles

In Southern California, attorneys working with people experiencing domestic violence tell a similar story.

“We haven’t seen any kind of proactive approach from the courts to ensure that the individual has relinquished their guns,” said Ayano Wolff, an attorney with the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles, or LAFLA.

California has no statewide statistics on how often armed abusers violate a restraining order and kill their partner, though it appears to be rare. The state Justice Department identifies about 50 domestic violence-related homicides each year in which the killer used a firearm. That’s compared to nearly 80,000 restraining order requests. More common appears to be the kind of terror CalMatters heard about in January from one of LAFLA’s clients, a 24-year-old woman who was staying at a domestic violence shelter after getting a restraining order against her husband.

The woman didn’t want her name used out of fear for her safety. But case filings showed that she told the court her husband had multiple guns and had threatened her with them.

“I have never done anything bad in my life,” she said through an interpreter, sobbing. “This man has made my life hell. I want justice.”

Nine months after that interview, she still was too fearful to use her name. Nothing in the court records indicates that her abuser, who admitted to having guns, has surrendered them.

One of her attorneys, Brenton Inouye, said it’s not surprising: “It’s really spotty as to whether it gets enforced or not.”

Years of warnings about flaws in the system

Judges, law enforcement professionals and advocates have been warning for years about such flaws in the system.

A 2005 report from a state attorney general’s task force indicated that California was failing to disarm abusers.

A state court system task force in 2008 found that people seeking restraining orders “erroneously believe that when the court orders the restrained person to relinquish firearms, either law enforcement or the courts will take steps to ensure that the order is followed.” Instead, the onus is on gun owners to comply, the report said.

A 2019 report from Sacramento County’s Domestic Violence Death Review Team flagged the issue, saying “proactive enforcement” of firearm relinquishment orders was “currently nonexistent.”

And last year, California’s independent watchdog commission said the state could do more to recover guns from abusers it knows possess registered firearms.

The focus has led to some changes, including laws aimed at identifying armed abusers. But experts say it’s not enough. Much of the problem — and potential solution — lies with family courts.

State law requires the courts to do a background check on alleged abusers before issuing a restraining order, including a search for legally purchased firearms. The requirement only applies to courts with the resources to afford such background checks, and the state Judicial Council — the court system’s policy-making body — was legislatively tasked with determining which courts couldn’t comply. But as CalMatters reported in July, that analysis was never done.

The council provided a statement to CalMatters, saying, “The council does not have a mandate to track which superior courts are conducting the background checks related to firearms relinquishment nor the authority to ensure enforcement of the relinquishment provisions."

Only 28 superior courts — fewer than half — have access to the state Justice Department’s web portal that would allow them to see whether an alleged abuser owns a legally purchased weapon, according to the attorney general’s office. While some courts told CalMatters their local sheriff’s office checks firearm registration for them, others acknowledged they don’t regularly get such records.

And even when courts do get information that an alleged abuser is armed with a registered — or unregistered — firearm, judges often fail to confirm that the guns are surrendered or to punish individuals who refuse to comply, interviews and case filings show.

“We have to come up with a better way of doing this. The honor system is not working,” said Paul Durenberger, a retired Sacramento County prosecutor who was in charge of his office’s family violence bureau.

II

The day after Calley made her report to Chowchilla police in May 2020, Julio Garay was arrested for assault, domestic violence, child abuse and making threats. The district attorney’s office didn’t immediately file charges.

Julio bailed out and was placed on the non-complaint calendar. That meant law enforcement would keep investigating and prosecutors could charge him before his scheduled court date of July 13.

On June 9, Chowchilla detective Brian Boivie went to the shelter to interview Calley. She told him about more instances of abuse, including some involving a gun, he later testified.

She told the detective that in November 2018, Julio returned home from the grocery store angry that their credit card was declined. He began beating her and then loaded her and the kids into the car and drove northwest out of Chowchilla just across the Merced County line.

She said Julio pulled into an orchard, angling the car so it would be easy to drive away. He grabbed a handgun and told her to get out.

“He then exited the vehicle himself with the firearm in his hand and pulled her out of the … passenger side of the vehicle and began kicking her and hitting her and forcing her down to her knees at the back of the vehicle,” Boivie testified she told him. “He mentioned that he was going to splatter her brains all over the kids, so tell them goodbye.”

He put the gun to the side of her head and pulled the trigger.

“She knew that the trigger was pulled because she heard the metal-on-metal click,” Boivie said.

CalMatters was unable to find evidence that Calley’s story about the orchard increased the urgency with which law enforcement approached the case. The Chowchilla Police Department denied requests for an interview and records because of ongoing court proceedings.

The department did not get any search warrants after her domestic violence complaints, law enforcement officials said.

The police did get Calley an emergency protective order after her initial May 15 report to police, which is a short-term restraining order that threatens abusers with criminal charges if they don’t stay away from the protected party.

On the form, filled out by a police officer, a box is checked stating that firearms were “searched for.”

It’s unclear what that means. The Chowchilla police chief declined to say. He called CalMatters’s questions about what his department did to disarm Julio Garay and why the investigation seemed to take so long “offensive.”

By mid-June, Calley was still in limbo, living at a shelter and reconnecting with family.

The Chowchilla Police Department, a small agency with one detective, was still looking into the abuse allegations — an investigation now in its fourth week — and the emergency protective order was set to expire.

A few days after her June 9 interview with Detective Boivie, Calley Garay turned to the family court in the hope a restraining order might protect her from her husband and his gun.

How many weapons are surrendered after restraining orders? There's no data

California has no data on how often alleged abusers surrender their weapons after a restraining order. The state court administration doesn’t track such information.

CalMatters asked the Los Angeles Superior Court, which handles a quarter of restraining order requests in the state, for records of domestic violence restraining order cases to attempt to compile such data. The court declined, saying it “does not fulfill individual data requests.”

CalMatters was able to review cases in four jurisdictions with more advanced case management systems. In Orange County, for instance, the search identified 219 domestic violence restraining order requests filed the same month that Calley Garay filed her request in Madera County.

The Orange County records show that in 25 cases, an allegedly armed abuser was ordered to stay away from someone — either temporarily or for as long as a few years — and turn in any firearms or ammunition they owned while the order was in effect.

In only one of those cases did the restrained party file paperwork indicating they had turned in guns. (In several instances, the accused abuser wasn’t formally served and the temporary order expired.)

Among the individuals who didn’t was a 28-year-old Garden Grove man who allegedly texted his ex-girlfriend, threatening to shoot into her house, and later drove by firing into the air, according to her request for a restraining order (CalMatters doesn’t name victims without their consent). The court granted the ex-girlfriend a full restraining order. Court records show the man didn’t attend the hearing, and there’s nothing in the file indicating the court followed up on the gun allegations.

A 30-year-old Pasadena man did attend the hearing on his ex-girlfriend’s restraining order request. She accused him of texting “I have my gun, so if you want to involve your brother, I’ll shoot to kill.”

“I’m going to execute you today. You’ll be gone forever. The minute you come outside, I’m going to shoot you,” he texted.

A transcript of the hearing shows the judge asked the man for his side of the story.

“Your Honor, I don’t dispute anything that she said,” the man stated. Despite the admission, the judge didn’t ask a single question about the supposed gun, nor did the judge tell the man he had to surrender his firearms.

A month after that hearing, the man allegedly violated the order by contacting her again. He was charged criminally with violating the restraining order 11 times from late July through August of 2020. The case is still open.

'For there to be that many cases of known firearms in the home and then that lack of follow-through when there is an opportunity for safety — we're failing.' — Jane Stoever, director, Domestic Violence Clinic at UC Irvine School of Law

CalMatters also reviewed cases from the first two weeks of 2020 to see whether there was a difference pre-pandemic. In nine cases where judges issued a full restraining order after a hearing against someone accused of being armed, none of the files included proof that any guns were surrendered.

“It’s devastating to hear this,” said Jane Stoever, a law professor who directs the Domestic Violence Clinic at UC Irvine School of Law. “For there to be that many cases of known firearms in the home and then that lack of follow-through when there is an opportunity for safety — we’re failing.”

CalMatters provided the list of cases and questions to the Orange County Superior Court.

A spokesperson returned written responses, saying judges are limited in what they can do without evidence and that the court is “not an investigating or prosecuting agency.”

“The Court has no enforcement authority. This is a basic fact of the Constitutional separation of powers,” according to the statement. "Judges may hold [a] review hearing, if it is brought to their attention by law enforcement or one of the parties that a restrained person has a firearm.”

A court spokesperson declined to talk about specific cases.

III

When Calley Garay filled out the restraining order request form, she checked the boxes saying Julio had a firearm and that he’d threatened her with it. And she included 11 single-spaced pages of abuse allegations, including the story about him putting a gun to her head in the orchard.

The court immediately issued a temporary restraining order, which told Julio he couldn’t have guns or ammunition and told him to surrender them to a licensed dealer or to law enforcement.

“The judge will ask you for proof that you did so,” the order stated.

Three days later, on June 15, a hearing took place in front of Judge Brian Austin, a former police officer elected to the bench in 2018.

A transcript of the proceedings shows there was talk about custody and hearing dates.

The judge — who had indicated on the record that he reviewed Calley’s filing — asked just one question about guns.

“Sir, there’s no information that you have any guns or firearms or ammunition. Do you think you have any of these items?” the judge asked.

“No,” Julio Garay replied.

Judge Austin declined to comment for this story, citing ongoing court proceedings.

The next hearing was July 6. The judge asked no questions about the gun; the issue of firearms didn’t come up, according to a transcript of the hearing.

The judge continued the case to the end of the month and told Julio that he still had to stay away from Calley and the kids. In the courtroom, Julio turned in his seat toward his wife, a witness later testified. He started tapping his foot.

There was not a third hearing.

Some courts do better than others

Even the advocates acknowledge that family courts are limited. Judges aren’t law enforcement officers; they don’t go out to search people’s homes. And experts say many don’t have enough resources to do more, given the volume of cases.

Still, some courts do have clear protocols to at least attempt to enforce firearm relinquishment orders.

Take Mendocino County on California’s North Coast. CalMatters reviewed 19 cases filed in Mendocino County’s Superior Court the same month that Calley filed her request in Madera. The records reveal a clear and consistent process for handling firearm relinquishment in restraining order cases.

Cindee Mayfield has been a Mendocino County judge for almost 24 years, including 10 in family court. She praised the state Judicial Council for educating judges about firearm issues and said such training encouraged her to develop her court’s approach.

After a temporary restraining order is issued or a hearing set, her court does a background check on an alleged abuser, looking for registered firearms. The search is noted in every case docket. If there is a registered firearm, or the person asking for the order indicates the abuser is armed, the judge will ask about alleged guns at a hearing to make a record of the issue. If alleged abusers deny owning a gun, the court has them sign a statement under penalty of perjury saying they don’t have guns. If there is evidence of a gun and no proof of surrender, the judge holds a special hearing.

In the three cases CalMatters found where the court issued a full restraining order against an allegedly armed abuser, two of the men filed proof they surrendered guns. In the third case, Mayfield held a special hearing because the man didn’t file such proof.

Mendocino is a rural county where hunting and ranching are a way of life, so the issue comes up often, Mayfield said.

“We have a lot of people that do have registered firearms,” she said. “They’re sometimes kind of loath to give them up. And so sometimes we do have to do follow-up hearings with people just to verify the fact they’ve complied with the law.”

Mayfield said it’s important to have clear, consistent policies.

“I do kind of feel bad sometimes because they want them for wildlife or snakes or what have you on their ranches,” she said. “But it’s like, at this point for the next three years, I’m sorry, you’re just not going to have guns because it’s not safe.”

The Legislature has made some efforts to force all courts to act more like Mendocino. A 2019 bill would have required family court judges to hold special hearings on firearm relinquishment, among other changes. As it stands, such hearings are optional in family court. (Criminal court judges can also issue protective orders when an abuser is charged with a crime. Those criminal court judges don’t have the same discretion and must hold hearings on firearms if they believe the subject of such a protective order is armed.)

The Judicial Council opposed the bill, saying it presented “workload challenges” and that significant procedural changes could affect court operations and lead to delays. The bill was ultimately gutted and replaced with something else.

Lawmakers came back at the issue this past year. The Judicial Council worked with the author to resolve “the procedural problems” of the prior legislation, according to the council’s statement. That bill — a more modest effort that still doesn’t require special firearm hearings — passed without council opposition.

IV

Julio’s 2020 date to appear before a criminal court judge was pushed back from mid-July to Sept. 14 because law enforcement needed time to interview the children, according to the district attorney. In texts to her cousin Rodriguez, Calley expressed frustration at the pace, mentioning COVID-related delays and including an angry, swearing emoji.

With her husband still out there and armed, Calley and the kids stayed holed up in a secret shelter outside the city, her family said.

“They were together,” her mother, Jodie Williams, said in a recent interview. “That’s all that mattered.”

Text messages between Calley and Rodriguez show the young mother’s hope for the future.

“Today we are celebrating freedom in many ways!!!” Calley wrote on July 4, 2020.

In another, she texted: “All the things he wouldn’t let me wear,” along with a photo of earrings, makeup and nail polish.

Calley was searching for apartments out of the area, near police stations, in case he ever came looking for her, Rodriguez said. And despite life in hiding, she was taking care of herself. She’d lost weight and scheduled a doctor’s appointment at Camarena Health in Madera for July 14, records show.

The day before that appointment, a receptionist at the health center called the number in the clinic’s system to confirm the date and time.

A man answered.

Julio hung up his cellphone after telling the receptionist that he would take a message for his wife. Calley would be at Camarena Health on East Almond Avenue in Madera at 1:15 p.m. the next day. He started getting his affairs in order. There wasn’t much time.

From a friend, he borrowed a white Chevy pickup truck with a pink crown decal in the back window and a dent on the rear passenger side. The morning of July 14, 2020, he arrived at the county clerk’s office right when it opened at 8 a.m. Visitor logs show he was the fifth person in the door.

There, he filed paperwork to have the home he was living in transferred to his adult daughter from a prior marriage. Then he went to an auto parts store to buy car window shades, which he’d need for what he did next.

Julio drove into the parking lot on East Almond Avenue sometime before 10:45 a.m. That’s when an administrative assistant at a dialysis center, which shares a parking lot with Camarena, went to Starbucks. The worker later testified that he saw a white pickup parked next to his and a man sitting behind the wheel.

The truck was backed into a spot and Julio had a clear view of the health center door. The window shades would have obscured his face from passersby but also shielded him from the midday sun. He sat there for hours in the 90-degree heat.

Sometime after 1 p.m., he watched the 2007 white Toyota Sienna minivan pull up and let Calley out with their two youngest boys, who were wearing matching jersey-style T-shirts, red with black sleeves. He saw her walk in and watched the minivan pull away to get gas and then return a short time later, parking a few spaces from the front doors of the clinic.

His oldest son, then 6, was in the parked minivan, a victim services worker in the driver seat. They talked about the boy’s favorite TV show until he fell asleep.

At 2:28 p.m, Calley exited the health center holding her 1-year-old in one arm with the 4-year-old walking next to her. She opened the sliding door on the passenger side so the older boy could get in. She leaned in to put the 1-year-old in his car seat.

Calley must have heard something because she whipped her head around. She shouted, “No,” before scrambling into the van, shielding her boys from their father, who was running toward them with a .380 pistol, arm outstretched, firing.

Julio Garay fired six times, hitting his wife in the head and chest — at one point placing his hand on the car for support as he leaned into the vehicle. Calley died between the front seat and middle row, her children in their car seats.

Coda

Police tracked Julio’s phone to a motel in Marina, two hours away in Monterey County. The local police there, including a SWAT team, arrested Julio that night. He surrendered peacefully.

The Madera police and district attorney’s office threw a team of skilled, veteran investigators at the case. In the end, they recovered an overwhelming amount of evidence. There were fingerprints, enhanced video showing the crown decal on the borrowed truck captured by the health center’s surveillance camera, partial DNA.

They searched the home where Calley and Julio lived, finding the broken hair brush behind a dresser — right where Calley had told them it flew during a beating. They got Julio’s adult son from a previous marriage to talk about the time Julio allegedly took that wife into the orchards and threatened to shoot her — just like the threat Calley had reported. And they talked to the girlfriend of another adult son who told them about Julio showing off a .380 pistol — the same caliber as the murder weapon. All of it corroborated what Calley had told them more than a month before.

All of it was too late.

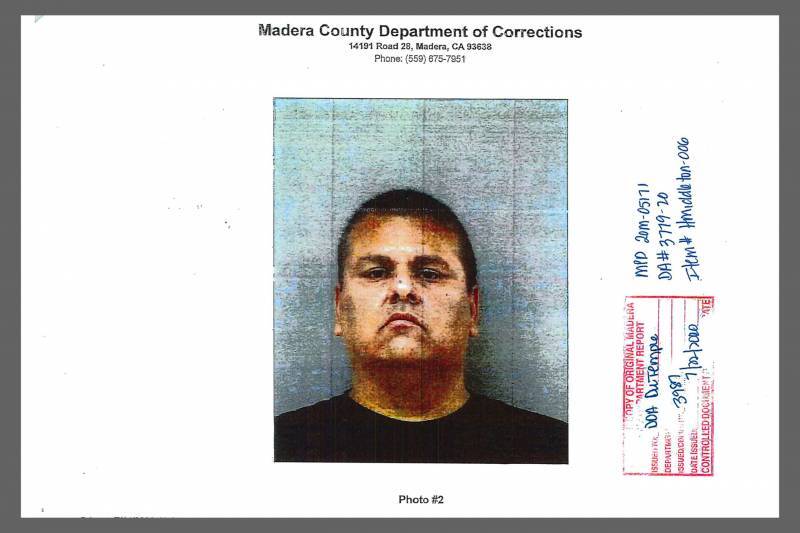

A top prosecutor in the district attorney’s office, Eric DuTemple, expertly laid out the evidence over the course of three weeks, starting in late September. Julio Garay didn’t testify in his own defense, and family members, who attended the trial, declined to participate in this story. The jury deliberated for a day before finding Julio Garay guilty on all counts and enhancements. He was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

After the verdict, Calley’s mom, Jodie Williams, stood outside the courthouse and talked about her daughter.

“She loved to laugh, and she was just a good kid. She’s a really good kid. Really beautiful spirit,” Williams said. “She gave her life for her children.”

Calley’s death spurred legislation aimed at protecting medical, education and other records from abusers. There’s been no discussion, however, about why Julio was armed and how to better disarm abusers.

After the conviction, Madera District Attorney Sally Moreno — a former police officer and Army reservist — talked about the case. As in many areas, domestic violence is a big problem in the community, she said.

“It’s been a rising issue the last several years. But it’s always an issue,” she said. “And it’s always going on in the background.”

Moreno spent years working domestic violence cases. Convictions are tough because the abuse often happens in private and witnesses sometimes stop cooperating. Moreno said she and the office did some soul-searching after the killing.

“We did look at it and it was painful to tear it apart and to hope that we hadn’t failed her somewhere,” Moreno said, adding that she doesn’t think they could have done anything to prevent the tragedy, given the lengths to which Julio was prepared to go.

She said there was no way to keep him in custody and the more serious allegations — which would have gotten him a longer prison sentence — took time to investigate.

She also said retrieving guns can be difficult. Law enforcement needs probable cause to get a warrant. And the sad reality is that “there are enough guns on the street and whatnot that if somebody wants to get a gun, they’re going to be able to do it.”

“We’d like to be able to confiscate people’s guns, but we have a long history of respecting people’s homes and property,” she said. “And so there’s a lot of hurdles to go over before we do those things, and the law tries to balance that.”

Law enforcement never was able to find Julio’s gun, which the prosecutor DuTemple mused during trial “is probably at the bottom of Monterey Bay right now.”

Law enforcement did find open boxes of bullets in Julio’s Cadillac Escalade with its vanity plate “GARAY1” when they arrested him in Marina.

They also found a manila folder on the floorboard behind the console. Inside was a copy of the domestic violence restraining order signed by a Madera County Superior Court judge — just a piece of paper after all.

If you or a loved one is experiencing domestic violence and need help, call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at (800) 799-SAFE (7233) or the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence at (916) 444-7163. You can also find local organizations in California at this site.

Outgunned, a CalMatters series, is supported by a grant from the Cohn family.