This week the Navy outlined its case against the sailor accused of setting fire to the USS Bonhomme Richard in 2020.

Three days of hearings showed how difficult it can be to prove arson.

Seaman Apprentice Ryan Sawyer Mays was charged with arson and willfully hazarding a vessel in the fire that destroyed the amphibious assault ship in July 2020.

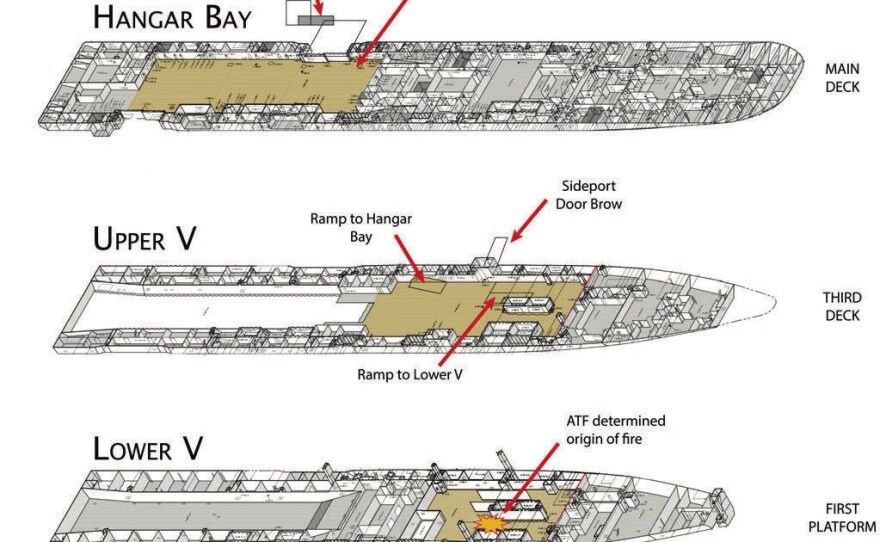

The U.S. Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms sent its National Response Team to San Diego. The team spent months combing the wreckage before declaring the fire was arson. Defense experts, including former ATF fire investigator Phil Fouts, poked holes in their conclusions. They concluded that naval investigators shouldn’t have ruled out the lithium ion batteries found in the area where the fire started or molten ends of two copper wires inside the engine compartment of a forklift parked in the hold, which may indicate there was a spark.

“It is one of the tougher crimes to prove and it does have a relatively low clearance rate, according to the FBI uniform crime report,” said Robert Schaal, a former arson investigator for the ATF, who now works for Gulf Coast Fire in Florida.

Whether in a building or on board a ship, proving a fire is arson is difficult, absent an eyewitness or a confession, he said.

“Sometimes you can prove it’s arson, but you can't prove who did it,” he said. “Sometimes you can't prove it's arson, so you never get to who did it, so there are a lot of complicating factors in arson cases that are not associated with other crimes.”

One sailor testified that he saw Mays going in the direction where the fire broke out, but there was no one standing watch in the lower vehicle bay — or lower V — an unassuming part of the ship, used to store equipment for the Marines, when they were on board. It was packed with construction material, hoses and large cardboard boxes, stacked nearly to the ceiling.

If the case goes to trial, Schaal expects the defense will raise the issue of the crime scene being contaminated. Investigators found a bottle at the scene, which smelled of diesel. An investigator marked it for collection, but the bottle was gone the next day. Only the tape tag was found. They did not find Mays’ DNA or fingerprints on the tag or anywhere in the area of the fire, including on a ladder that investigators suspect was the escape route.

Prosecutors portrayed Mays as hating the Navy.

Naval Criminal Investigative Service interviewed Mays for more than 9 hours on Aug. 20, 2020, before taking him into custody. Mays reportedly lied about details of his time in SEAL basic training. He said the Navy “sucked.” But never admitted to setting the fire.

A military police officer testified that as the sailor learned he was being taken into custody, a dejected Mays said “I guess I did it.” Though, she wasn’t sure whether he was serious.

“He has continued to maintain his innocence in regard to these allegations,” said Gary Barthell, Mays’ civilian attorney. He spoke briefly at the end of three days of hearings.

“Obviously, his attitude has changed now given allegations that have been made against him. But his intent was always to return back to BUD/S and be a SEAL,” Barthell said.

The Navy painted Mays as upset about being sent to a ship after he voluntarily left training to be a SEAL, called Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL at Coronado. BUD/S is famously difficult, with a high failure rate. Anyone who doesn’t make it is sent to the regular Navy. It’s actually a problem, says Lawrence Brennon, a former Naval officer and a law professor at Fordham University.

“They go back to his days when he was in BUD/S when he wanted to be a seal and you know it's a problem when you have a smart person who is frustrated,” he said. “And goes from the world where he thinks he's going to be a seal and all the things that entails, in reality, as well as in his vision and then get sent to a ship, where he or she has been given a cruddy job.”

The Navy declared the USS Bonhomme Richard a total loss after the fire burned for more than four days in San Diego. Though no one died, it was still a very public failure for the Navy. There is pressure to find those responsible, says arson investigator Schaal.

“I would say, the higher the profile the case,” Schaal said, "the more pressure there is on the government to have accountability, so here you've lost a multi-billion dollar vessel.”

The hearing officer will likely take several weeks to review the testimony and reports before recommending to Vice Adm. Stephen T. Koehler whether Mays should face a court martial.