Emmy McLarty was desperate to get her best friend Josh Palmer sober and off the streets. She had gotten sober herself and found housing and she wanted the same for him.

McLarty asked Palmer whenever she saw him if he was ready to start the journey towards a new life. He always declined, but promised she would be the first to know when it was time.

The last time they had this conversation in March 2021 was also the last time she saw him.

Palmer died of an accidental fentanyl overdose a week later.

He is one of the hundreds who have died from the highly addictive drug in San Diego County since the beginning of the pandemic.

Data from San Diego County Medical Examiner’s office shows fentanyl overdoses in 2020 are more than four times higher than 2018, with at least 446 people dying in 2020 with the drug in their system.

“We anticipate seeing as many as 1,200, maybe more, deaths across the county as a result of unintentional drug overdose in 2021. We are up against a challenge, the ceiling of which we don't understand.”Dr. Luke Bergmann, director of San Diego County Behavioral Health Services

What's more, in the first nine months of 2021, more people have died with fentanyl in their systems than last year: at least 534 people as of the end of August 2021. Even more people are expected to die by year’s end, said Dr. Luke Bergmann, the director of San Diego County Behavioral Health Services.

“We anticipate seeing as many as 1,200, maybe more, deaths across the county as a result of unintentional drug overdose in 2021,” he said. “We are up against a challenge, the ceiling of which we don't understand.”

RELATED: San Diego Saw Sharp Increase In Fentanyl Deaths Throughout Pandemic Lockdowns

The increase in overdose deaths is a trend researchers are seeing nationally as well. According to The New York Times, more than 100,000 people died of drug overdoses within the first 12 months of the pandemic. That’s 30% more than the previous year.

Fentanyl is a deadly trifecta — it’s cheap, it can be easily disguised as a different drug and it’s 50 times more potent than heroin, according to experts. And the disheartening truth is fentanyl-related deaths are mostly avoidable, said Dr. Ryan Marino, a Cleveland-based addiction medical specialist.

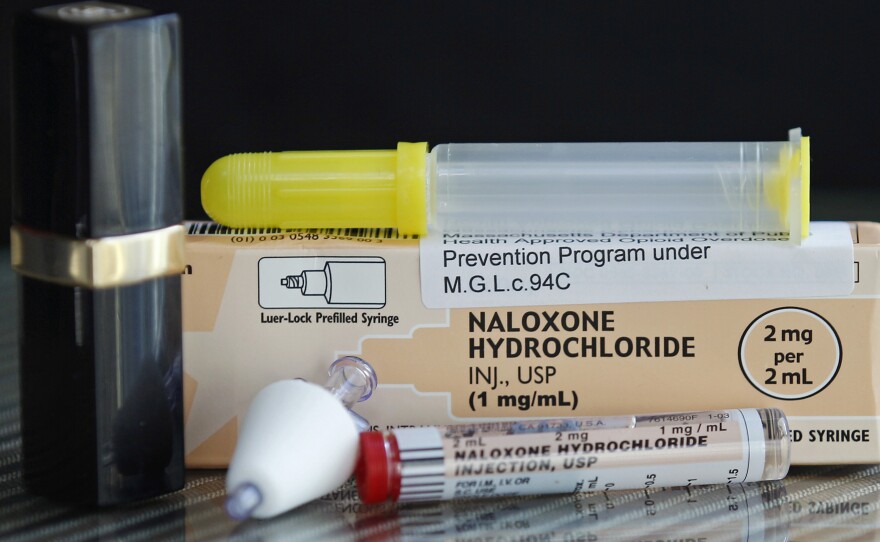

That’s because fentanyl’s antidote is easy to access. Naloxone, an opioid overdose medicine commonly known as Narcan, can be bought over the counter for as low as $20. But people are afraid to give people Narcan because they don’t want to touch someone suffering an overdose, which compounds on other stigmas that drug users face, Marino said.

“People don't deserve to suffer or die or anything like that just because they use drugs,” he said. “And so to me, this is just more stigma that kind of hurts people with substance use disorders and addiction. And even people who just casually use drugs, it prevents them from getting appropriate treatment.”

In San Diego County, white people were overrepresented in fentanyl overdose deaths in 2020. About 61% of the people who died were white, whereas 49.5% of the county is white, according to U.S. Census data. Meanwhile, 18% of the people who died were Hispanic, 11% were Black and 3% were Asian or Pacific Islander.‘Boogeyman personality’

McLarty doesn’t know if anyone saw her friend Palmer and tried to help him during his overdose. He died on a staircase outside of the nonprofit Fraternal Order of Eagles, mere feet away from the bustling University Avenue in Hillcrest. McLarty said she didn’t know what the last minutes of his life were like, but hopes he wasn’t alone because people were too afraid to help him.

“Because I think that is most people's absolute worst nightmare come true,” she said.

Marino said misinformation about the danger of touching fentanyl can sometimes stop people from helping others.

In July, the San Diego Sheriff’s Department released a video about a rookie deputy falling to the ground and struggling to breathe after handling fentanyl while wearing a mask and gloves. The department later said the overdose claims were not verified by a medical professional.

RELATED: Sheriff's Department Releases Unedited Video Of Deputy Allegedly Overdosing On Fentanyl

Marino said bystanders are not at risk of absorbing fentanyl through the skin.

“But for whatever reason, over the past few years, fentanyl has kind of taken on this boogeyman personality,” he said.

This misinformation can also impact the loved ones of those who die of fentanyl overdoses. Diann Hotchkiss lost her husband Derrick to a $15 hit of fentanyl in 2019. Derrick was sober when they met. He had admitted to struggling with addiction years prior, but Hotchkiss said the man she fell in love with had a large and consuming presence who always made sure to care for those he loved. This changed when he started using fentanyl shortly after their son was born.

When her husband overdosed, Hotchkiss vividly remembers calling 911, hoping paramedics could save her husband.

Instead, emergency responders came in and told her she needed to immediately evacuate the family home. She was told their backyard, car and the home office had tracings of fentanyl that could have killed her and her son, Dominic. She and Dominic left their home the day Derrick died and never returned.

Marino said the team did not have the correct information.

“Any drugs near an infant can be problematic, but it's not something that is going to get into your body unless you are injecting or snorting it,” Marino said. “It doesn't just cross through the skin. It isn't just getting into the air. And unfortunately, we've seen a lot of these law enforcement agencies have used hazmat and have used a lot of the PPE that we didn't have for the pandemic on these situations where it is chemically and physically impossible to be such a concern.”

Changes at county

San Diego County’s Behavioral Health Services department has shifted its methods for treating the rising fentanyl epidemic after the new Democratic majority took over the Board of Supervisors, said Bergmann.

Now the county is focusing on harm reduction, an alternative drug use treatment plan that focuses on human behavior and societal impacts of drug use instead of the punishment or incarceration route, he said. A common example of this is providing clean needles to users to reduce the spread of disease.

“It's extremely important that we get them resources to reduce the likelihood of harm,” Bergmann said. That can include Naloxone, clean tools to inject with, primary care, shelter and showers.

“The spirit of it is getting people what they need and what they want, even if they're not in a particular moment, able to commit to a trajectory towards abstinence,” he said.

The county has also created Community Harm Reduction Teams to help with harm reduction, specifically for the homeless community. Bergmann said the teams are only in the city of San Diego for now, but they are working to make it a county-wide initiative.

“We're doing everything we can to make sure that people are getting access to the formal clinical care that we do know over the long haul reduces the likelihood of overdose, death and other harms associated with substance and misuse,” Bergmann said.

Diann Hotchkiss’ husband died before these changes had the chance to make an impact and before the pandemic hit. She worried his mental health would have pushed him towards the drug if he had lived through COVID-19.

“I also believe that if he had gotten clean, he wouldn't have survived the pandemic,” she said. “I think he would have relapsed.”