From the very minute they moved in together, Kyona Beatty and Ken Zak knew they wanted to create a home that reflected their identity as a couple.

They immediately went to work on making their historic house in Mission Hills into their own personal sanctuary — a calm and peaceful environment decorated in rich earth tones and perfumed with sage and palo santo.

“Everyone who has come into this house has had that moment where they walk and they go, ‘Oh my god, I feel so good. It feels like a sanctuary,’” said Beatty, who is an ayurvedic healer.

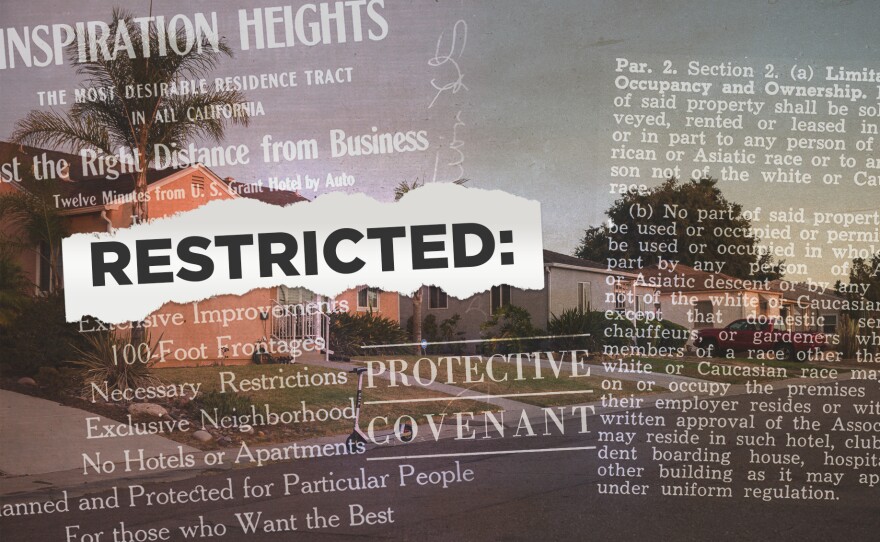

But in the course of renovating their home, they discovered a crack in their sanctuary — a racially restrictive covenant attached to the subdivision that includes their home.

Beatty is Black and Zak is white. It felt wrong that the 1920 deed to their shared home essentially banned Beatty from living there.

Racially restrictive covenants were outlawed nationwide in 1948, but the language — even though it’s no longer enforceable — remains on the deeds of older homes everywhere.

After talking about it, Beatty and Zak decided they had to do something.

“That’s a shadow over this property,” Zak recalled thinking. “But so to me it was like 'Let’s remove that, let’s remove that shadow from this house.'”

In California, homeowners have the right to strike this language from their property records by requesting a Restrictive Covenant Modification.

Zak, a retired lawyer, quickly researched and started the process. On the last day of February 2020, the couple successfully had removed the racially restrictive language from their deed.

“We were leaving the building and I was like, ‘We did it during Black History Month,’” Beatty said. “And we gave each other a (fist bump) and it was done. It did feel really good.”

Beatty says that taking the extra steps to remove the restrictions was worth it. “It’s like the ultimate smudge stick,” said Beatty. “You can just get that energy out of the equation.”

For Beatty and Zak, removing the racially restrictive language wasn’t just a symbolic gesture but a way of resetting the spiritual foundation of their home.

And they want others to consider making the change in their own deeds. In March 2020, Zak wrote an article in San Diego Uptown News detailing how San Diegans can check and modify their deeds. The law does give counties the discretion to waive a $95 fee that comes with the modifications. San Diego County, however, refused to waive the fee in Zak’s case.

How state law is helping

In recent years there has been a push by members of the state legislature to streamline the process and create a more accurate record of how prevalent such restrictions were in the state.

In 2009, a bill authored by former Assemblymember Hector De La Torre, D-Los Angeles, which would automatically delete any racial restrictions every time a property was sold, passed the Legislature.

However, then Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed the bill , saying racially restrictive covenants were already illegal.

This year, Assemblymember Kevin McCarty, D-Sacramento, and other lawmakers again took the issue on with AB-1466.

“In the era of George Floyd and racial reconciliation through our country and state, we're looking at the lens of our policies,” McCarty said. “This is one that we're taking a second look at and I'm really proud that this has had bipartisan support.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the bill in September. The new law streamlines the process of removing racial covenants by requiring title and escrow companies as well as real estate brokers to assist home buyers wanting to remove the language.

It will also make it so restrictive covenant modifications are indexed and made to the public by the county recorder.

McCarty, who is half Black, is passionate about this legislation. His home has a racially restrictive covenant and he believes that just like old segregation signs designating “white-only” drinking fountains have been taken down, it’s time to remove racial restrictions out of property records.

“This is an opportunity to right a wrong,” McCarty said.

Doomed to repeat history

Not everyone feels that removing the racist language is the best way to reconcile the state’s discriminatory past.

Michael Dew has no interest in striking out the language of his home in San Diego’s El Cerrito neighborhood.

“I don’t want it to be lost 20 years from now — that this was a part of society,” Dew said. “I say be aware of history or be forever doomed to repeat it.”

Since discovering the racial restrictions attached to his 1951 house, Dew has found that a lot of people refuse to believe they exist until he shows them. He’s worried that if the language is removed, people will forget the history, which he still thinks too few people know or talk about.

When he found the racial restriction on his deed, the third-generation San Diegan became interested in learning about his family’s experiences with racism. He was particularly interested in the stories of his grandfathers, both of whom moved to San Diego from the South because of the military.

Dew found that getting those types of stories out of family members wasn’t easy.

His mother said she can’t recall talking about any issues around housing discrimination when she was growing up. His paternal grandfather said he tried to buy a house in Bonita and was told not to come back.

“You really have to pull teeth to get older relatives to talk about these things and I think that’s a piece of the trauma of it all,” Dew said. “That’s when I start thinking about the psychology of these restrictive covenants. Maybe they did know about it, but I think of my mom saying they shielded us from it.”

“You really have to pull teeth to get older relatives to talk about these things and I think that’s a piece of the trauma of it all ... That’s when I start thinking about the psychology of these restrictive covenantsMichael Dew, San Diego County homeowner

When faced with racism, Dew said his grandparents didn’t dwell on it or share it openly with their kids because they had to survive and find ways to thrive, “to be stronger than what society makes of you.”

He understands why his elders felt that way, but he also knows that when we avoid the hard truths of history, they are often erased.

From racial restrictions to NIMBYism

Dew is not the only one who sees a throughline between the racial covenants of the 20th century and present day.

“You see it a lot in NIMBYism,” said Nancy Kwak, a University of California, San Diego historian. “People are pushing back against changes that would make a neighborhood more accessible, so a really simple example is more affordable housing.”

Kwak says when San Diegans talk about property values and things like “I earned this house” or “this is something that I deserve,” she hears the same logic that was used in the past to defend segregation.

Although such statements aren’t overtly racist, many homeowners’ perceived right to control who can and can’t live near them helps maintain the inequities embedded in the current housing system, say Kwak and others.

“Make no mistakes about it, yes the covenants are gone, but the zoning took its place and it’s been wildly effective,” said Ricardo Flores, executive director of LISC San Diego, a local nonprofit committed to affordable housing in the region.

With more than half of San Diego’s residential areas zoned for single-family homes, Flores wants to see higher density housing built in these areas.

“We need to provide wealth, building opportunities for those individuals and those families who were left out,” Flores said. “We need to provide those wealth building opportunities in communities where the land has a higher value, not because it’s fair, but because of laws in the past that made it so and continue to make it so.”

The same mindset that gave rise to racial covenants a century ago was on display during the 2020 presidential election when former President Donald Trump made “protecting the suburbs” for white people a key plank in his campaign.

Speaking to a crowd of supporters in Midland, Texas in July 2020, Trump drove the message home.

“People fight all their lives to get into the suburbs and have a beautiful home,” he said. “There will be no more affordable housing forced into the suburbs.”

A month later, he and Ben Carson, then Secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, penned an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal entitled, “We’ll Protect America’s Suburbs.”

The tagline read: “We reject the ultraliberal view that the federal bureaucracy should dictate where and how people live.”

Without mentioning race, Trump clearly painted a picture of an imagined white-suburb under attack from “outside” forces that would change the neighborhood and perhaps even the value of one’s home.

Across the country and in San Diego suburbs have become increasingly diverse, but in this case, many viewed the use of the word “suburb” as a euphemism for "white."

While racism is just one of a number of reasons why California remains mired in an affordable housing crisis, experts argue it’s important that the history of housing discrimination remain front-and-center in our present-day debates.

Because whether people choose to remove racially restrictive covenants, like Beatty and Zak, or keep them as evidence, like Dew, the goal seems to be the same — to remember the past in order to build a more equitable future.