Michael Dew still remembers the day in 2014 when he purchased his first home — a newly renovated ranch style house with an ample backyard in San Diego’s El Cerrito neighborhood.

It took years of scrimping and saving, but the then 35-year-old had finally accomplished what his mother had wanted for him.

“My mother always felt that homeownership is the number one thing that I should pursue in my life outside of my college degree,” said Dew, who is a third-generation Black San Diegan. “It's a roof over your head, it's an established home, we really believe in the concept of home.”

Dew’s house is just a few blocks away from his paternal grandfather’s house in Oak Park, the so-called “Big House” he had spent his childhood visiting. It didn’t take him long to become a neighborhood fixture — king of the block’s cookouts.

But one day a few years ago he decided to look at the home’s original 1950 deed and found something he wasn’t expecting: a racially restrictive covenant.

“There’s this nice paragraph that tells me I didn’t belong,” Dew said.

“That neither said lots or portions thereof or interest therein shall ever be leased, sold, devised, conveyed to or inherited or be otherwise acquired by or become property of any person other than of the Caucasian Race.”

One thought hit him almost immediately — neither of his grandfathers, one who fought in the Korean War and the other in the Vietnam War — could have purchased his home when they were his age.

“I’ve been fully aware of Black history in America. I wasn’t surprised it was there, but it’s just upsetting that I was in San Diego County,” Dew said. “I thought maybe LA County, maybe in the north, but San Diego County, where both my grandfathers retired from the military after decades of service.”

Speaker 1: (00:00)

Racially restrictive covenants once prohibited, black, Latino, Asian, and Jewish families from living in certain neighborhoods across San Diego county, KPBS, race and equity reporter. Christina Kim tells us how they shape the region's housing in this special three part series

Speaker 2: (00:18)

Ever since 2014, when Michael du bought his home in San Diego is El Sorito neighborhood. He's been a fixture at his blocks parties and happy hours around the barbecue, but every now and then something happens that reminds him that as a black man, he didn't always belong like the time an older neighbor mistook him as a gardener.

Speaker 3: (00:37)

So I'm talking and I was going to refill a drink and an older woman. I wish I knew who she was. Uh, you know, just kinda caught me off guard. And she said, so are you one of the gardeners? And I was like, why would a gardener be at a happy hour

Speaker 2: (00:49)

Years later when reading over the 1950 deed of his ranch style home do figured out why his older neighbor might've said such a thing. The deed included a racially restrictive covenant

Speaker 3: (01:01)

That neither said lots nor any portion thereof shall ever be lived upon or occupied by any person other than of the Caucasian race provided. However that if persons not of the Caucasian race be kept there in by a Caucasian, strictly in the capacity of servants or employees actually engaged in the services of each occupant or in the care of said, premises for said, occupant gardener

Speaker 2: (01:29)

For years hired help was all he could have been in his home. Racially restrictive covenants were legal documents attached to deeds, subdivisions, and entire developments. They took off at the turn of the 20th century,

Speaker 4: (01:42)

Early in 1927, they were on, you know, three quarters of the new homes in America and about half law homes. So they spread very quickly and became a dominant way of limiting who could do

Speaker 2: (01:55)

That's Jean Slater, an affordable housing specialist and author of freedom to discriminate. He says real estate brokers and developers created and enforced racially restrictive housing covenants across the nation.

Speaker 4: (02:07)

They created a whole system, including all the other brokers in the city and the homeowners association, neighborhood associations, public officials who work together to make certain a city or a neighborhood remain. All

Speaker 2: (02:21)

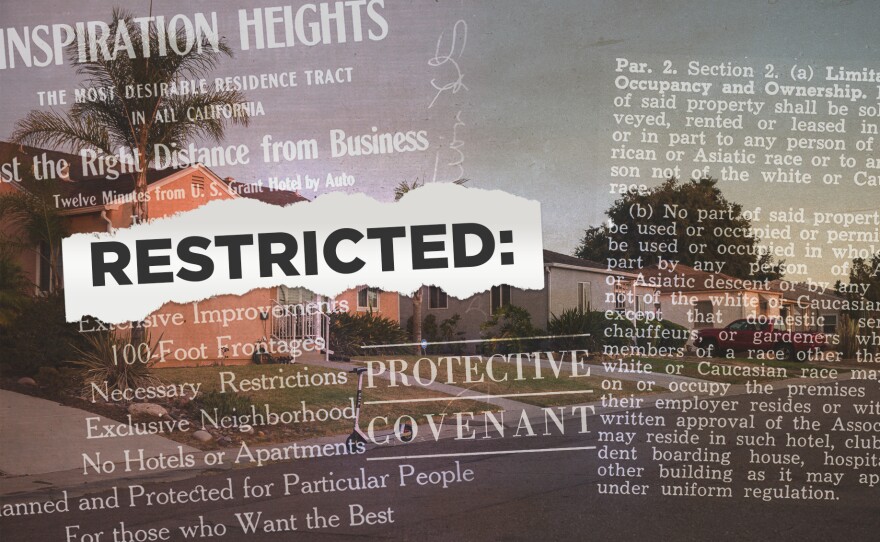

San Diego was at the forefront of this national trend, a sample of San Diego city deeds from 1910 to 1950, found that every single one at a racial restriction advertisements for San Diego properties from the earliest 20th century, all allude to these racial restrictions. One from 1910 for lots of inspiration Heights, which is now part of mission Hills says the area has the necessary restrictions and is planned and protected for particular people. In other words, white and affluent, black, Asian, Latino, and Jewish San Diegans were all bought, locked out of the city signature neighborhoods like LA Jolla, north park and mission valley. And instead purposely segregated into Southeast neighborhoods in 1948, the Supreme court struck down the legality of racially restrictive covenants. But as we see with do's home, they continued into the fifties as the patterns of racial segregation that they in concert with redlining steering and zoning created patterns that continue to shape San Diego. Today. It's not hard to see says Denise Mathis, president of the California association of real estate brokers.

Speaker 5: (03:32)

You're African-American Hispanic or why we still use the interstate eight as the dividing mark. Okay. So south of the eight, you expect one thing in north of the eight. You expect something else.

Speaker 2: (03:48)

San Diego is more segregated today than it was 30 years ago. According to a recent UC Berkeley study, and much of the segregation is still marked by interstate eight, with more wealthy, wider communities in the north. As a black woman from San Diego Mathis, his own grandfather was impacted by housing discrimination that continued long after racially restrictive covenants became illegal.

Speaker 5: (04:11)

I always remember him telling us that he looked at a house right outside of mission valley on top of the hill, and he was told he could not purchase there. So what would that home in mission valley be worth that I could have inherited compared to the home that they stabbed him to buy in Oak park? Where would my wealth being

Speaker 2: (04:38)

Day homeownership plays a bigger role in creating wealth for black families and for white families, but gaps continue to persist. Only 30% of black San Diegans own their homes compared to 61% of white people in San Diego, according to a 2018 Redfin study,

Speaker 3: (04:55)

To be more evolution of thought as to the impacts of some of the rules and regulations of the past, that kind of determined where your socioeconomic position is today.

Speaker 2: (05:05)

It's why Michael do wants more people to know about racially restrictive covenants. Like the one in his home, the home, his grandfathers, both veterans couldn't have bought the overt housing discrimination they faced may have been illegal for decades, but we're still a long way from understanding, let alone undoing the generational harm. These practices have caused.

Speaker 1: (05:27)

Joining me is KPBS race and equity reporter, Christina cam, Christina.

Speaker 2: (05:32)

Welcome. Hey Maureen, what prompted

Speaker 1: (05:35)

You to look into the history of these restrictive covenants?

Speaker 2: (05:39)

This is a topic that's actually near and dear to my heart. When my family left San Diego and moved to the bay area. I remember my dad, who's Korean looking at the deed of our home in Moraga and actually finding in that deed that it said something like no Orientals were allowed to live there. And it just stuck with me. I must have been in third grade and I always wanted to know more. So when the opportunity came up to start digging into what this meant for San Diego's history, I just knew that as a race and equity reporter, this was such a great way to understand just how race is embedded in the regions housing stock.

Speaker 1: (06:14)

Yeah, let's talk about that. Why did this kind of racial restriction become so popular in real estate? I mean, did real estate agents say it had something to do with property value?

Speaker 2: (06:26)

These racial restrictions and within covenants really started to take off because after 1917, there was a us Supreme court decision, which actually made government instituted racial zoning illegals, because that was made illegal. This left a huge loophole for individual homeowners, property developers and real estate agents to do it through other means. And so here is where we really start to see racially restrictive covenants, which are kind of more privatized take off. And to your point, so it sort of snowballs from there. And according to Jean Slater, who released a book this year called freedom to discriminate, and he looked really into the history of racial covenants, as well as real estate agents. He says, realtors really developed this idea that racially mixed neighborhoods led to lower property values to your point. So what he found is that there was no real studies that prove that that, that proved that racially mixed neighborhoods actually led to lower property values, but it became something of a self fulfilling prophecy. And then it became encoded in practices like red lining. And to this day, you often hear, oh, what will happen to the property values? And it's really rooted in this myth and this ideology that was created by real estate agents, right? As they were beginning to privatize and professionalize and the turn of the century

Speaker 1: (07:41)

Now from your report, it sounds as if there were some but not many legal actions taken to enforce the covenants here in San Diego. So how was the segregation actually maintained?

Speaker 2: (07:54)

So racially restrictive covenants were only as strong as the neighbors and the will of the neighbors to enforce them. So while there is evidence of legal action, there were other ways that segregation was kind of implemented and maintained. For instance, there's a practice called racial steering in which real estate agents might steer people from one neighborhood instead of another. And you hear that in my piece, I speak to a realtor named Denise who says her own grandfather was, you know, steered away from certain neighborhoods because he was a black man. And the second part is the way that neighborhoods were just welcoming or not welcoming to people of color, our reporting partners at I knew source found evidence of people of color, actually going door to door before buying a home in order to just introduce themselves to their neighbors, to make sure that they weren't going to be pushed out after the fact. Um, and so in addition to that, we know there's, you know, there was, there were some, you know, legal ways in which this was brought up what we also know that violence happened. I didn't find any evidence of that here in San Diego, but there are many accounts in Los Angeles, for instance, with black GIS coming home from world war II and moving into, you know, wider middle-class areas. And they were met with burning crosses and, you know, very threatening neighbors who just didn't want them to live there.

Speaker 1: (09:11)

So black, Latino, Asian, and Jewish families not only had to contend with restrictive covenants in neighborhoods, but even if a seller would defy the covenant lining meant they probably wouldn't be able to get alone. Isn't that right? That's right.

Speaker 2: (09:25)

Racially restrictive covenants were just one tool in a larger toolkit of racially discriminatory practices. Redlining used a lot of the same ideology that was embedded in racially restrictive covenants, for instance, federal money wouldn't flow to new developments and unless they had such restrictions. And then the maps that, you know, we all are so familiar with carved up our cities into areas of risk based if they were racially mixed, or if they predominantly black, Latino, Asian, or immigrant communities lived there.

Speaker 1: (09:54)

Now in the past, you report that when neighborhoods began to age like Valencia park and Logan Heights, then people of color were allowed to move in, but now kind of the reverse is happening as black and brown residents sometimes find themselves priced out of their neighborhoods. So I'm wondering are soaring home prices becoming a sort of new racially restrictive covenant?

Speaker 2: (10:17)

I'm not sure if soaring home prices are the new racially restrictive covenants because there's no paper trail of follow. And this isn't about legally enforcing anything but soaring prices on top of an already significant racial wealth gap are definitely going to mean that only the wealthy will have opportunities to buy and create more generational wealth here. And I know that's kind of causing a little bit of fear and anxiety for folks. I was just speaking to a local business owner yesterday in skyline, who says that people are worried that these kinds of new sewers and new apartments really aren't being built for them. They're, they're not being built for the largely black, Latino and Filipino community that already lives there. And so there's a fear of displacement. And to your point, seeing a lot of segregation and changes in our housing that are again rooted in race,

Speaker 1: (11:05)

We'll hear part two of your report on covenants tomorrow. So can you give us a preview?

Speaker 2: (11:10)

Yeah. So stay tuned tomorrow. We're going to be taking a closer look at Rancho Santa Fe's, protective covenant. Some residents there want to stop referring to the area as the covenant and have a real reckoning with Rancho Santa Fe's exclusive and discriminatory paths.

Speaker 1: (11:25)

All right, then I've been speaking with KPBS race and equity reporter, Christina Kim, Christina. Thank you very much.

Speaker 2: (11:31)

Thank you.

What is a racially restrictive covenant?

Racially restrictive covenants made it impossible for Dew’s grandfathers and other Black, Asian, Latino and Jewish people to buy homes or plots of lands in neighborhoods across San Diego County.

Attached to parcels of land, subdivisions, neighborhoods and individual homes, racially restrictive covenants explicitly detail who could and could not live there.

California was at the forefront of these restrictive covenants. Realtor-developer Duncan McDuffie in the Bay Area was one of the first to create a high-end housing development in Berkeley and restrict residency by race in 1905.

Recently professionalized real estate agents and brokers were the driving force behind the use of these covenants, which exploded nationwide between 1920 and 1950, according to Gene Slater, author of the book, "Freedom to Discriminate".

“It took the organization of real estate boards beginning in the 1900s to systematically agree among their members that they would not allow minorities to move into white neighborhoods,” Slater said.

“It took the organization of real estate boards beginning in the 1900s to systematically agree among their members that they would not allow minorities to move into white neighborhoods.”Gene Slater, author of "Freedom to Discriminate"

Realtors justified the use of racial restrictions by creating and sustaining an ideology around homeownership that would come to define housing in the U.S. — that racial diversity led to lower property values and that neighborhood homogeneity was both desirable and a homeowner’s right.

“They basically created a new idea in America: It’s your constitutional right to exclude other people from where you live,” Slater said.

San Diego was fast becoming a boom town at the turn of the 20th century, just as these new ideas were taking hold.

The San Diego Realty Board, now called the San Diego Association of Realtors, formed around the time of these first covenants in 1911. In a sample of San Diego housing deeds from 1910 through 1950, Leroy Harris, a doctoral student at Carnegie-Mellon University, found every single one of them had racial restrictions.

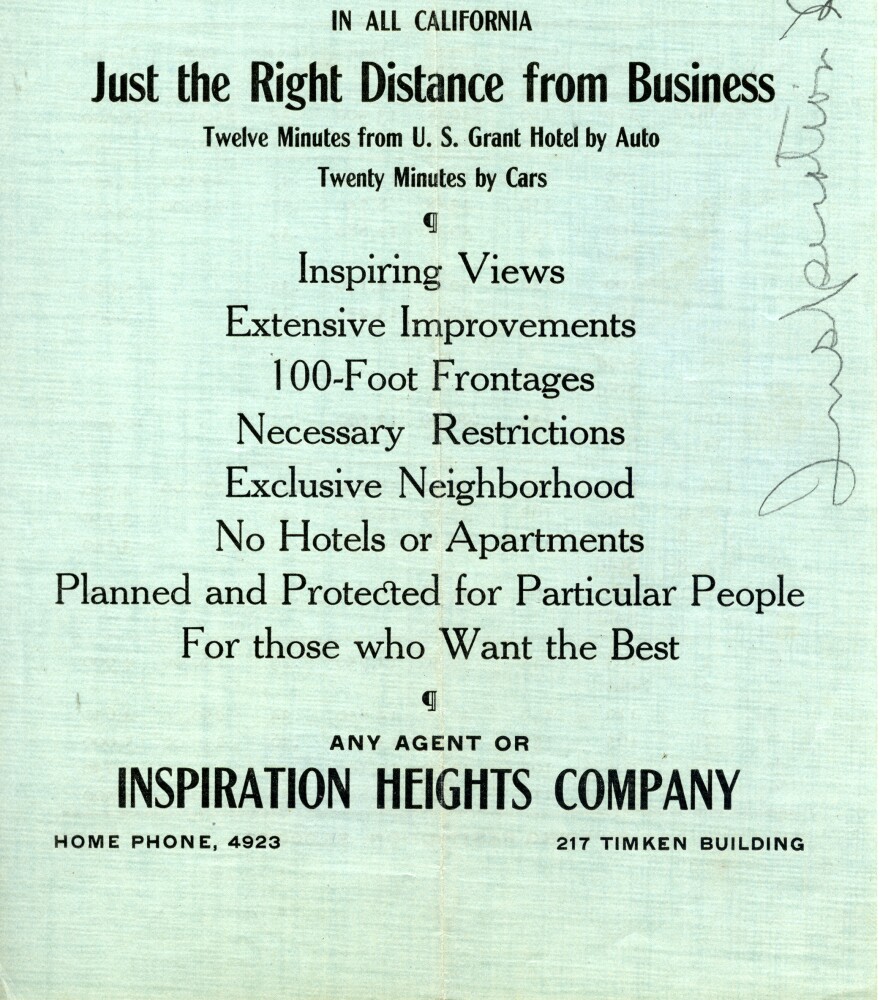

Early pamphlets selling subdivision and new homes used the language of restrictions to attract homebuyers. A 1910 advertisement for lots in Inspiration Heights, an area that’s now part of Mission Hills, describes the area as “the most desirable resident tract in all California” that has “necessary restrictions” and is “planned and protected for particular people.”

An undated booklet advertising Lomacitas, a neighborhood in Chula Vista, seeks to entice buyers through a fictional story of a man telling his friend Gordy about this new community. After showing Gordy the golf course and lovely views, he notes: “No undesirables will be allowed to buy.”

In other words, only certain white and affluent homeowners were welcome in many of San Diego’s premiere developments at this time.

Most Black, Latino, Asian and Jewish people were essentially locked out from purchasing in new development. Instead, as the housing stock in formerly restricted areas of Southeast San Diego like Logan Heights and Valencia Park began to age, people of color were allowed to come in.

Racially restrictive covenants were only as strong as the will of a neighborhood’s homeowners to enforce them. So there were cases in which a Black or Mexican American family were able to purchase homes that had a covenant.

“The covenant requires keepers,” said Andrew Wiese, a professor of history at San Diego State University. “It requires people who see it in their interest, a large group of people who see it in their interest not to break the covenant.”

That said, the covenants were legal documents and there are examples of San Diegans using courts to enforce housing discrimination.

In a 1944 case, two white homeowners from Golden Hill sued a Black family for living in the area saying their presence would depreciate property values and that “non-Caucasians have available for use and expansion easterly, southerly and westerly.”

Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the 1948 case, Shelley v. Kraemer, that racially restrictive covenants were legally unenforceable. But though it was a landmark case, it did little to slow housing segregation or, as evidenced by Michael Dew’s deed, the use of racially restrictive language well into the 1950s.

Racially restrictive covenants worked in concert with redlining

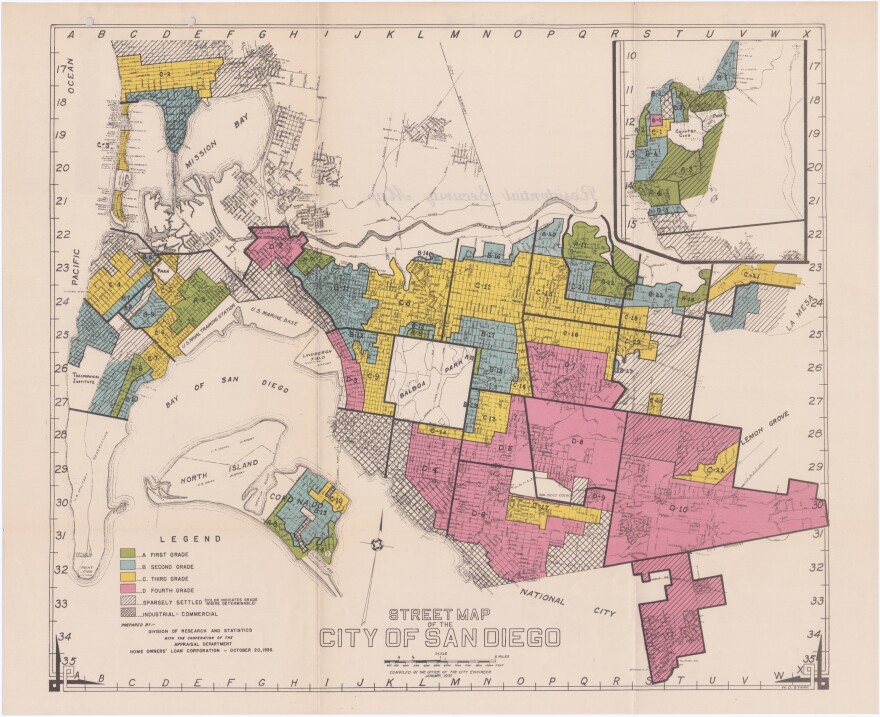

The racial segregation popularized by the use of racial covenants was hardwired into San Diego through redlining — the government-sponsored system of denying mortgage loans and services to finance the purchase of homes in certain areas.

In the midst of the Great Depression and a completely decimated housing industry, the federal government created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in 1934 to spur homeownership.

The FHA completely transformed housing in the U.S. by introducing federally-insured and long-term mortgages, but such financial products were only for white homebuyers. Nationwide, of the $120 billion worth of new government subsidized housing built between 1934 and 1962, more than 98% went to white families.

“The FHA, in effect, required racial covenants,” Slater said. “So you had a system both for new construction with racial covenants and of existing neighborhoods with redlines that together meant almost no minorities got loans from FHA anywhere in the county.”

Staffed and created by many of the same real estate industry leaders that had created the system of racial inclusion in the housing market, the FHA’s programs perpetuated the debunked myth that diversity engendered lower property values.

The FHA redlined most of Southeast San Diego as “hazardous,” which essentially cut off investment from flowing into the area.

The 1937 Federal Writer Project’s guide to San Diego notes that the southeast area of the city is where “San Diego’s Mexican and Negro communities” reside and notes “the buildings and houses are old and in need of repair, there is considerable poverty and very little wealth; if any part of this city could be called a slum, this is it.”

An indelible mark on America’s 'Finest City'

Nearly 20 years after racial covenants were deemed illegal, San Diego civil rights groups including the city’s Urban League told the California Fair Employment and Practices Commission that San Diego was one of the most segregated areas in the county.

In 1965, Howard H. Carey, associate director of the San Diego Urban League, reported that 95% of the city’s Black population was forced to live in the southeast section of the city.

“Race still plays a part in real estate.”Denise Matthis, San Diego real estate broker

San Diego remains highly segregated over half a century later, according to a recent study by UC Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute. UC Berkeley researchers found that people of color still live in segregation in Southeast San Diego while Northern and coastal areas are areas of high white segregation.

“Race still plays a part in real estate,” said Denise Matthis, a local real estate broker.

As a Black woman and current President of California Association of Real Estate Brokers (CAREB), Matthis sees how Interstate 8, which was built in 1964 and cuts horizontally across the county, has become the region’s de facto racial and ethnic boundary.

“Whether you’re African-American, Hispanic or white, we still use Interstate 8 as the dividing mark. Okay, so South of the eight, you expect one thing and North of the eight, you expect something else,” Matthis said. “Now is that the correct way of doing it? Probably not, but it’s a true fact.”

Matthis knows firsthand the generational cost and impact housing discrimination can have on a family. She grew up hearing her grandfather talk about how he looked at a home in Mission Valley and was told he could not purchase there.

“What would that home in Mission Valley be worth that I could have inherited, compared to that that they steered him to buy in Oak Park,” said Matthis. “Where would my wealth be?”

Once relegated to certain parts of the city and region, people of color had lower starting home values than white homeowners, but their costs of ownership were higher and their properties appreciated at slower rates.

The disparities that began a century ago have only compounded over time.

According to the Urban Institute, homeownership plays a bigger role in creating wealth for Black families than white families, with housing equity comprising 60% of Black homeowners total net worth compared to only 43% of white families.

“Homeownership is a funny thing because homeownership is not one thing, there are various kinds of homeownership,” said Nancy Kwak, a University of California, San Diego history professor.

In 2018, homes in majority-Black neighborhoods were valued at 23% less than similar quality homes in comparable non-Black neighborhoods, according to a national study by the Brookings Institute, a left-leaning think tank.

Home prices are rising across San Diego city and county. The median home price in June 2021 reached $750,000. But it’s important to note what areas are driving these home prices.

“There still needs to be more evolution of thought as to the impacts of some of the rules and regulations of the past that kind of determine where your socioeconomic position is today.”Michael Dew, San Diego homeowner

The formerly restricted neighborhood of Mission Hills is still predominantly white. The median price of a home there is a little over $1.5 million, according to Zillow, the online site that tracks real estate values.

On the other hand, the median price of a home in Encanto, which is largely made up of Black, Latino and Asian families, is a little over $630,000.

Michael Dew feels lucky to have bought his home in his 30s. He doesn’t think he would be able to break into the current housing market, but he’s also aware that in many respects he’s an outlier.

A 2018 study by Redfin, a real estate brokerage, found that only 30% of Black people in San Diego own their homes compared to 61% of white residents. Because homeownership is deeply tied to economic outcomes these disparities are significant.

“There still needs to be more evolution of thought as to the impacts of some of the rules and regulations of the past that kind of determine where your socioeconomic position is today,” Dew said.

Dew loves his neighborhood and is friendly with his neighbors, but every now and then something will happen that reminds him that for a long time he didn’t belong in his El Cerrito home.

A few years ago when he had recently moved into his home on West Overlook Drive, Dew attended a neighborhood happy hour. As a University of Utah alumni and football fan, Dew wears red every Friday to show support for his team. That Friday he joined his neighbors wearing his red polo shirt.

He had just finished chatting with a neighbor and was on his way to the bar to pour himself a drink when an older woman stopped him and asked, “So, are you one of the gardeners?”

It stopped Dew in his tracks.

“Maybe I looked like I worked at Target, but I definitely didn’t look like I was a gardener,” recalled Dew.

He politely told her he was not and that he owned the home down the street and walked away. But that’s when he remembered the second racial restriction outlined in his deed:

"That neither said lots nor any portion thereof shall ever be lived upon or occupied by any person other than the Caucasian in Race; provided, however that if persons not of the Caucasian Race be kept thereon by a Caucasian strictly in the capacity of servants or employees actually engaged in the service of such occupant."

The neighbor mistook him for a gardener because for a long time a gardener or a servant to a white person is all that he could have been in his neighborhood.

The encounter has stayed with him.

“It kind of reminded me that it hasn’t been very long since we weren’t allowed to be in the same classroom or in the same neighborhood,” Dew said. “If you want to look at where we are today, to know why southeast San Diego has the demographic it does and why it has some of the statistics that it does, it gives me a little bit more understanding of it.”