Updated July 15, 2022 at 3:38 PM ET

WARSAW, Poland — In a refugee center outside the Polish capital, the posters on the wall urge recent arrivals to come forward. "Help Ukraine — Give Testimony!" one reads. "Help us punish the criminals."

But relatively few have come forward in this vast expanse of tightly packed cots and still air.

Poland is one of 18 countries to launch criminal investigations into war crimes in Ukraine. The task is a huge challenge — especially for investigators looking to talk to survivors of mass rape and sexual assault. Reports suggest that rape by Russian soldiers may be widespread, though Russia has denied the allegations. The United Nations, human rights groups and Ukrainian organizations are all documenting and working to corroborate reports of sexual violence in Ukraine.

As Ukraine's first rape case connected to the Russian invasion gets underway, prosecutors say there are many more but acknowledge the challenges ahead. Rape is considered a war crime, but cases that make it to trials or tribunals are remarkably rare because survivors are traumatized and often feel shame and reluctance to testify.

The Polish Border Guard said as of last week, it had recorded more than 4.5 million people coming in from Ukraine since the Russian invasion began on Feb. 24. Dariusz Barski, a Polish national prosecutor, tells NPR that about 1,000 Ukrainians in the country have given testimonies about possible Russian war crimes — but not a single rape survivor has stepped forward so far.

"They are volunteers, witnesses and victims who are testifying here," he says, "and this is part of the problem that not all the witnesses want to testify."

Ukrainian rape survivors do talk to Dr. Rafal Kuzlik, a Warsaw obstetrician and gynecologist who specializes in reconstructive gynecology. He treats war rape survivors in his clinic and currently has seven patients from Ukraine. He offered his services on a Facebook page as the first reports of mass rape surfaced after the Russian invasion.

"We can heal [the] body much easier than we can heal brains," he says. "A big percentage [of war rape survivors] commit suicide."

There is still shame and fear of being ostracized, he explains. And unmarried women fear rejection by future partners.

For wartime rape survivors in Germany, the news from Ukraine stirs up terrible memories

Sexual assault is hardly new in war, though focusing on it has often been taboo. In Germany, the subject has received greater attention in recent years. During the waning days of World War II, some 2 million German women were raped by Soviet and Allied forces after they defeated Hitler's army, according to historians. Germans kept quiet about the trauma for decades, due to shame mixed with guilt about Nazi atrocities.

In postwar Germany, the mass rapes were an open secret, but few reported it. Fewer still wanted to know about it. In Russia, the topic remains toxic to this day and is publicly called a "Western myth."

In the past few years, some German women have come forward to recount their wartime experiences. Ninety-two-year-old Brigitte Meese decided to tell her story for the first time in 2020 in a German magazine.

"If you ask me where I was when the war stopped, I was there where nobody wanted to be — under the Russians," she says. "We really were allowed to live as long as they allowed us to live," she says of the Red Army soldiers. "That was bad for the women, some were violated 40 or 50 times."

She remembers her mother pushing her cap down low to hide her face, but still a Russian soldier pulled her out of a crowd by the wrist. "I hardly knew what was happening, I was so naive. Of course, I was violated," she says.

The news from Ukraine stirs up those memories. "It's happening again," she says.

Meese believes rape was intended as punishment for atrocities the German army had earlier inflicted on the Soviets — "punish a people as a whole by raping the women," she explains.

When asked what she would tell a Ukrainian woman who has been raped by Russians, Meese responds: "I would tell her to forget about it if she can. I think even nowadays, it's something you want to forget."

A Berlin exhibition spotlights wartime rape

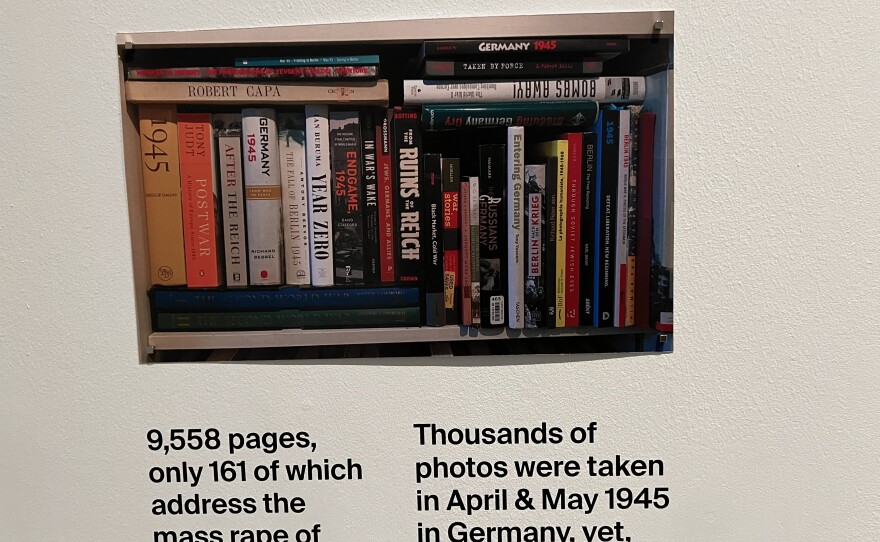

Buried wartime memories are addressed in an exhibition tackling the topic of wartime rape at this summer's Berlin Biennale art show. The exhibition, "The Natural History of Rape," notes that despite all the books, the films, the photos of those postwar years, the mass rapes are hardly mentioned.

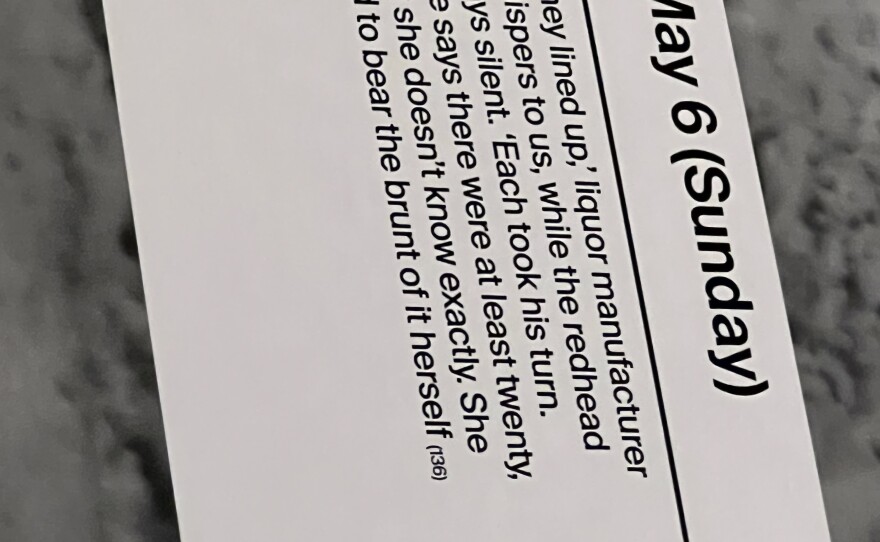

It features the text of a postwar diary published anonymously in 1959. Titled A Woman in Berlin, the book documents rape in a remarkably frank and unsentimental account. At the time of publication, the German public scorned it and attacked the author for besmirching the honor of German women.

It became a bestseller when it was republished in 2003. Attitudes had changed by then, says Karen Hagemann, a German-American historian at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

"There is no way to deny that these rapes happened," she says.

Rape as a "tactic of war"

Rape "was not understood as an independent war crime until relatively recently. There's been emerging case law, " says Oona Hathaway, an international law professor at Yale University. "It's surprising to look back now where it should have been obvious."

The first case was prosecuted in the tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in 1993. The Rwanda tribunal came next.

During Rwanda's civil war, up to a half a million women and children were raped or murdered in the course of 100 days in 1994. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda found, for the first time, that mass rape during wartime is an act of genocide.

In 2008, the United Nations Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1820 that recognized sexual violence as a "tactic of war to humiliate, dominate, instil fear in, disperse and/or forcibly relocate civilian members of a community or ethnic group," and can help determine whether genocide has been committed.

Now, Ukraine is reporting a campaign of sexual violence as part of the Russian invasion. This is another test for making systematic sexual assault a part of future war crime trials or tribunals, says Hagemann.

"Only if sexual violence is included can we do justice to the whole population," she says.

But many survivors remain reluctant to testify, says Kuzlik, the Warsaw ob-gyn.

"Even if this war ends tomorrow and all trials will start in a year, I don't think they will be ready. They will not want to talk about it," Kuzlik says about his patients. "We will have to wait for a long time. I think Putin will be dead. So, history will judge. I'm sorry, but it will be like that."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))