More than two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, people are getting used to the idea that the virus isn't going to disappear. Scientists predict that COVID will likely become endemic, a permanent part of our lives that we'll have to learn to live with and manage.

In fact, only one human disease has ever been completely eradicated: smallpox.

"Smallpox was one of the most devastating diseases ever since humanity can remember its history," says Daniel Tarantola, who was a medical officer with the World Health Organization's smallpox eradication program in the 1970s.

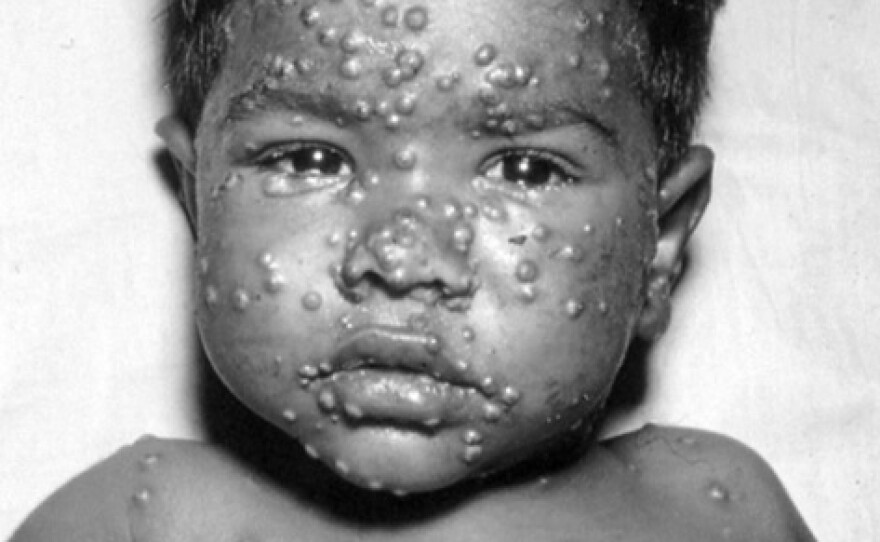

People infected with smallpox would develop a painful rash all over their bodies. The most deadly strain of the virus, called Variola Major, killed almost a third of its victims. Those who recovered were typically scarred, and sometimes blinded, for life.

"When we started smallpox eradication, people said, 'You're crazy, you can never eradicate smallpox,'" says Alan Schnur, who was an epidemiologist with WHO's smallpox program.

In 1975, Tarantola and Schnur were based in Bangladesh, which was the last country in the world to have cases of Variola Major. And in the fall of 1975, they traveled to a remote village on an island on the Bay of Bengal to meet a toddler who had recently fallen ill.

That toddler was Rahima Banu, and she would come to hold a remarkable place in history, as the last known person in the world to be infected with naturally-occurring deadly smallpox.

After thousands of years and millions of deaths

Smallpox circulated for more than 3,000 years. The earliest known evidence of the disease is found on the mummified bodies of several ancient Egyptian pharaohs, whose skin is studded with the characteristic bumps. The virus is estimated to have killed at least 300 million people worldwide during the 20th century.

In 1796, Dr. Edward Jenner, an English physician, developed a vaccine for smallpox — the world's very first vaccine. By the early 1950s, vaccination campaigns had eliminated smallpox from the West, but the disease remained endemic in many parts of the world.

Then, in 1967, the World Health Organization set out to stamp out the virus entirely.

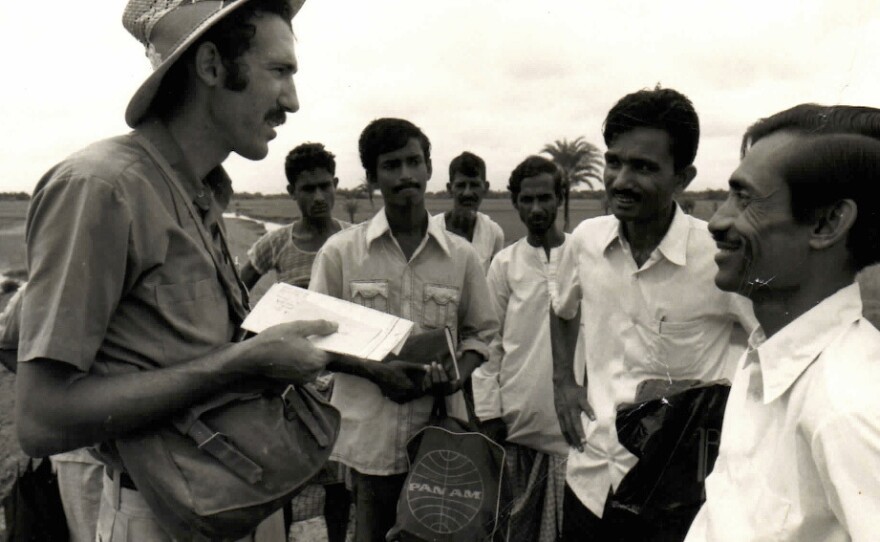

Doctors and epidemiologists from around the world traveled from country to country, where they would collaborate with local health workers. They visited markets and went house-to-house, showing people photographs of smallpox and asking for information about outbreaks. Wherever they found a smallpox patient, they would isolate them and vaccinate everyone in the surrounding households.

By the fall of 1975, Bangladesh was the only country left to still have cases of Variola Major, the deadly form of smallpox. But when you're trying to eliminate a disease, how do you know when you're done?

Smallpox eradication in Bangladesh

In Bengali, smallpox was known as guti boshonto, or "spring rash," a nod to the season when transmission was usually highest.

Daniel Tarantola, a French doctor, was recruited to join WHO's smallpox program in Bangladesh in the early 1970s. He joined a team of health workers from more than 20 countries, including both the United States and the Soviet Union.

In November of 1975, Tarantola and a few colleagues gathered in Dhaka to celebrate a thrilling milestone: their team had not received a single report of smallpox in two months.

"The smallpox eradication campaign had been an exhausting exercise," Tarantola told Radio Diaries. "And so we were celebrating the end of a very difficult road."

WHO's headquarters held a press conference to announce to the world that they believed they'd seen the last case of Variola Major. The next day, Tarantola received three telexes. The first two were congratulatory.

Then a third message arrived from their colleagues based on Bhola Island, on the Bay of Bengal.

"One active smallpox case detected Village Kuralia," it read. "Date of detection 14/11/75 ... details follow."

"This was a pretty dramatic setback," says Tarantola.

The telex Tarantola received was about Rahima Banu, a toddler from the remote village of Kuralia. Her family lived in a house built from cattail leaves and with an earthen floor. Her father was a day laborer who fished and felled trees, and her mother was a housewife. She was their first child.

Banu was part of a chain of smallpox transmission that went undetected by health workers for several weeks. Her 10-year-old uncle, who lived with Banu's family, got sick first.

"I went up to him and jumped on him, and started playing with these marks he had on his body," Banu told Radio Diaries through a translator. "On that very night, my mother saw three pimples break out on my forehead, and by the morning, I had it all over my body."

Alan Schnur, the American epidemiologist, traveled to Banu's home with Stanley Foster, the head of WHO's smallpox program in Bangladesh, to confirm that her infection was smallpox.

"There was some civil unrest at the time, so they had announced that all WHO international staff are restricted to Dhaka," Schnur remembers. "We got into the Jeep and slouched down. I put some sort of cloth over my head, so that they wouldn't see that there was this international WHO staff breaking the regulations."

The journey involved an overnight launch, a speedboat, a drive, and finally, a walk to Banu's house.

Tarantola arrived soon after and found Banu's mother sitting on a bamboo bed, holding her child, whose face, arms, and legs were covered with white spots. Banu, fearing the visitors, began to cry. Tarantola took a few black-and-white photographs of Banu crying in her mother's arms.

"My mother was shocked," Banu says. "She couldn't say a single word."

A question of containment

The health workers explained to the family what the procedure would be to make sure the illness didn't spread to their neighbors. The whole family was isolated in their home, and Banu's father was paid so that he wouldn't have to leave for work.

Banu's neighbors were then hired to guard her family's home, limit the number of visitors, and make sure any visitors were vaccinated before entering.

"They set up three camps around our house," Banu says. "Everyone in the area made money off of it."

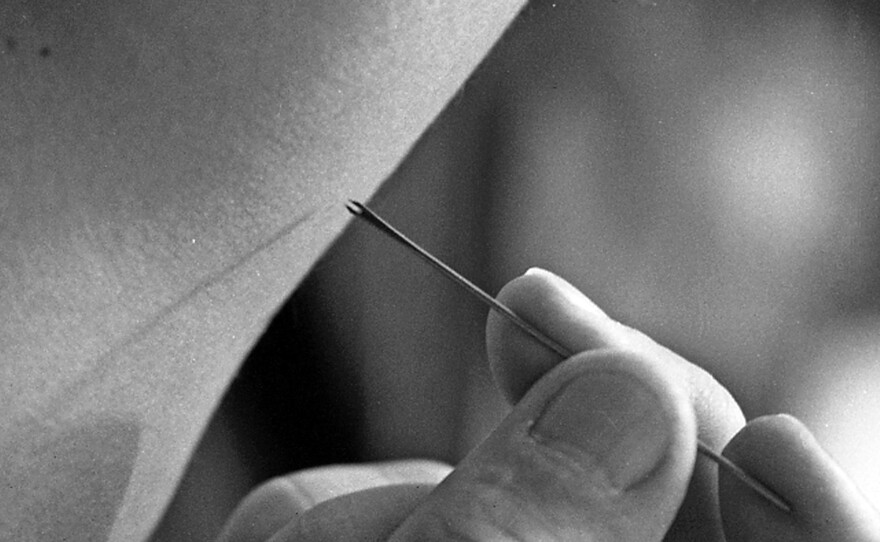

Health workers also hired locals as volunteer vaccinators. They were trained over a couple of hours to inoculate their neighbors using what was called a bifurcated needle, an innovation in the eradication program that allowed a person to be successfully vaccinated using just a small drop of vaccine.

Once trained, teams set out to vaccinate everyone living within a 1.5-mile radius of the house, which included more than 18,000 people.

To reassure locals that the vaccines were safe, health workers used to vaccinate themselves in front of them.

"I must have vaccinated myself 10,000 times in Bangladesh during the time I was there," Tarantola says. Because he was already immunized, those extra vaccinations had no effect on him.

Teams of vaccinators would go from house to house in the middle of the night, to make sure they arrived when people were back from working in the fields.

"I remember one house," Schnur says. "It was a two-story house, and this guy opened the window and said, 'Are you crazy? It's two o'clock in the morning. What are you doing here? Go away.''" But Schnur continued knocking, explaining they could not leave until everyone in the house was vaccinated. The man eventually let them in.

The end of smallpox

After vaccinating and searching the area around Banu's home for several weeks, health workers concluded that there were no other active smallpox cases nearby.

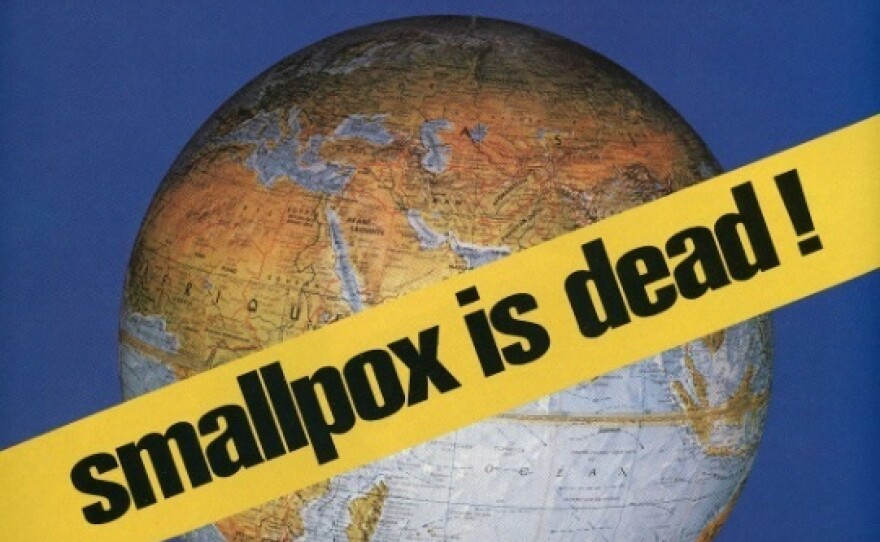

Still, health workers continued looking for cases across Bangladesh for two more years, and it wasn't until December 1977 that smallpox was declared eradicated in Bangladesh once and for all. During those two years, a much milder form of smallpox, called Variola Minor, was also stamped out in Ethiopia and then Somalia.

Finally, in May 1980, the World Health Organization declared that smallpox in all its forms was gone forever. The virus now exists only in two labs, one in Russia and the other in the United States.

Despite efforts to eradicate other human diseases, including polio and malaria, to this day the smallpox eradication program remains the only one to have succeeded worldwide. Tarantola and Schnur both attribute this, in part, to the fact that smallpox was a very visible disease with no inapparent cases.

"You could see it," Schnur says. "And that's why COVID-19 is so difficult to control, because you have people walking around with no symptoms and spreading the disease."

It wasn't until she was a teenager that Rahima Banu learned she was famous for having the last known naturally-occuring case of Variola Major in the world.

Banu recovered from smallpox, and had no long-term health problems aside from dotted scars all over her body. Because of those scars, she says she has experienced social discrimination.

"I don't look beautiful with these scars," Banu says. "If I wouldn't have had this disease, honestly, I could have married off to a wealthy family."

But Banu did marry. It was an arranged marriage, and her husband didn't see her before the wedding, but he accepted her. "He likes me as I am," she says.

Banu's husband is a day laborer who drives a van and does farm work; and Banu, like her mother, is a housewife. They have four children, the youngest of whom is in eighth grade. The family lives in a village near the one where she grew up. She owns a number of animals, including many geese that provide eggs for the family.

The family has very limited financial resources. During the COVID-19 lockdown, Banu was sometimes without food, and she cannot afford to take one of her daughters, who suffers from an illness that causes swelling in her hands, to the doctor.

Still, Banu speaks gratefully about her life. Her husband loves her and takes good care of her, she says. And she's enjoyed the attention and visits she's received over the decades from public health workers and journalists curious to meet the person who survived the last known case of deadly smallpox.

"I'm healthy. I have a family. I have children. My parents are alive," she says. "I have everything."

This story was produced by Alissa Escarce of Radio Diaries, with reporting and translation by Dil Afrose Jahan. It was edited by Joe Richman, Deborah George, and Ben Shapiro. Additional translation help by Kasara Hassan. Thanks to Nellie Gilles, Mycah Hazel, and Stephanie Rodriguez.

Additional thanks to Leigh Henderson for archival recordings of the November, 1975 WHO press conference. And thanks to the GBH archive for access to its 1985 documentary The Last Wild Virus, which included a scene featured in this story of Daniel Tarantola reenacting his work in Bangladesh.

You can find a longer version of this story, and other stories like it, on the Radio Diaries Podcast.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))