BEIJING — The window shades are drawn, the air's filled with cigarette smoke and tension. About three dozen people, mostly men, huddle around a table, in silence — all that can be heard is an unmistakable chirp.

It's a cricket fight.

Fall marks cricket fighting season in China, a sport believed to date back more than a millennium. In recent years, it's gained popularity with new generations. Some of the games go on covertly in small backrooms. Others, such as annual face-offs held in the southern metropolis of Hangzhou or the port city of Tianjin, are splashy, televised affairs.

Big money is involved. The little critters themselves are usually cheap — around $5 to $10 — but the most elite fighters can end up being worth a small fortune in a country where millions of dollars are spent on cricket sales — and cricket care — each year. And though betting isn't allowed, some games still see a surreptitious but robust exchange of money on the side.

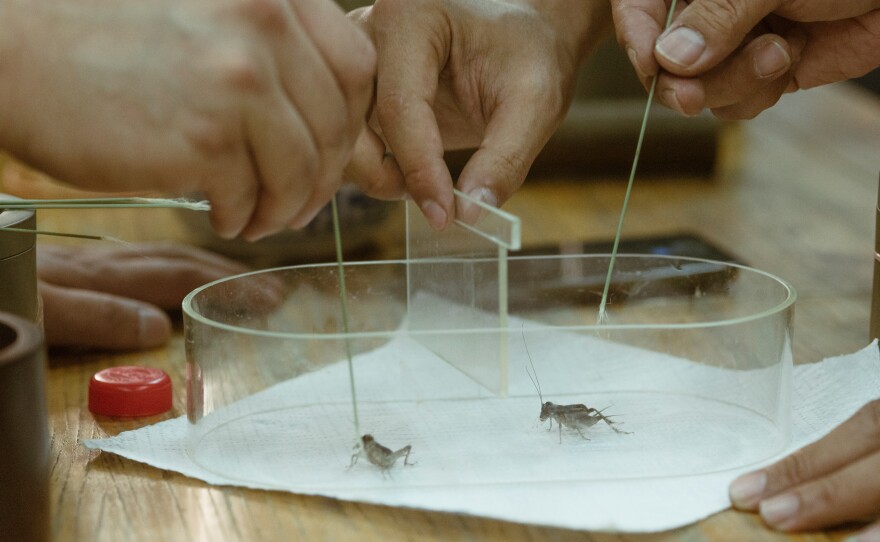

Here's how the game works. Two crickets — always males — are weighed to the closest hundredth of a gram and then paired off by weight class like prizefighters. They are placed in a clear plastic ring nearly the size of a dinner plate, with a dividing wall separating the two insects. A referee signals go time, then slides out the ring divider to let the bugs face off.

The owners poke a special reed in to lightly brush their crickets, which goads them into fighting. The critters lunge and swipe their pincer-like mandibles at each other. A referee closely monitors the tiny combatants, noting the number of attacks and retreats.

In one fight in this smokey room, there's a quick tussle of just a few seconds, but one of the crickets isn't able to keep its grip on the other and backs off. The referee declares it the loser. Both crickets are quickly put back into clay jars. They are precious enough that their owners never let them fight to the death, and injuries are rare.

Where the bugs are

Each of the men — and again, virtually all involved are male — have worked for weeks to get here. They had to obtain, train, and finesse their crickets for weeks to get ready for fighting season from September to October.

That laboring usually starts in the cornfields of northern China. Yang Yu'ai, a cricket vendor at the Tianqiao Market in Beijing, explains how her relatives fan out each August with nets and headlamps into the miles of corn stalks near her home in Shandong province.

Cricket enthusiasts wax poetic about the province because of the alleged fierceness of its six-legged fighters, which are supposedly fortified by Shandong's rich soil. Ningyang county in Shandong produces especially coveted bugs, the sale of which the county government says brings in about 600 million yuan ($94 million) in revenue a year.

The result from Yu's back-breaking hunt: hundreds of male crickets a year. The most expensive one she's ever sold cost nearly $400.

"My family has experience. They know to look for crickets with good-shaped heads and big mandibles. Ones with a fighting spirit!" says Yang.

"This year's crickets have good, hard mandibles because it did not rain too much. The rain produces crickets with soft mandibles," she explains.

These are high-maintenance critters

Zhao Jiuling is a committed cricket competitor. He catches his own crickets spending nearly two weeks trawling through fields in Hebei and Shandong provinces before dawn each day.

"You're looking for good teeth, good mandibles. A big, broad head, because you have jaw muscles. The bigger the head, the better the muscle," he says. Cricket hunters also pay attention to a complex array of other factors, such as the color of its head, its weight and the timbre of its chirp.

Zhao brings a few dozen of the best prospects back to Beijing to undergo training and feeding. Much of his intensive preparation is simply facing off his own crickets against others at home or in friendly matches to get a sense of each insect's quirks.

Outside the fighting ring, the critters are high maintenance too. Zhao lets me help clean out his ceramic cricket jars. They have been coated in a special type of "worm tea" — made from the manure of a moth native to southwestern Guizhou province. According to traditional Chinese medicine, the tea provides a cooling effect that complements the bug's body chemistry.

In each jar, we also add a little clay house for the cricket, the right mix of soils and a carpet of rice paper. "I don't want them to walk around with bare feet, because they have these tiny claws at the tip of their legs. When they're damaged they cannot hold their ground when they're fighting," Zhao explains.

Each night, he cooks a nutritious meal of grain and bean powder for them every night. "They're very picky," he says.

Better in the ring than between the sheets

The crickets are picky about their mates, too. The week before, Zhao carefully matched up his fighters with female crickets. "Sometimes they don't like each other. Domestic violence happens both ways. Sometimes the females eat the males," he says.

A few of his male crickets won't mate, which hinders their fighting abilities, because cricket enthusiasts believe their pets fight better after mating. Some of Zhao's male crickets have to have their bottoms washed in a special solution he concocts to unclog their genital openings, which have been covered up by overly large wings — also a sign of a good fighter, but bad for reproduction.

Zhao loves his crickets so much it sometimes gets in the way of his own love life. Women tell him he's crazy, he says.

What makes it worth it? The thrill of the competition, he says. The glory of victory. And a singular dream.

"We always had this dream when we were a little child when we could one day have the king of fighters. We've been searching for it for many many years. We're going to go through our lives year after year in the hope that we could have one," he says.

So far, Zhao has had some good fighters. He even sold one for about $1,500 in September. But he's still looking for the one to beat them all.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))