While the United States worries about a repeat of the Great Depression, Germans have another crisis in mind: the hyperinflation that hit them more than 80 years ago. And inflation may be on German Chancellor Angela Merkel's mind when she meets with President Obama in Washington on Friday.

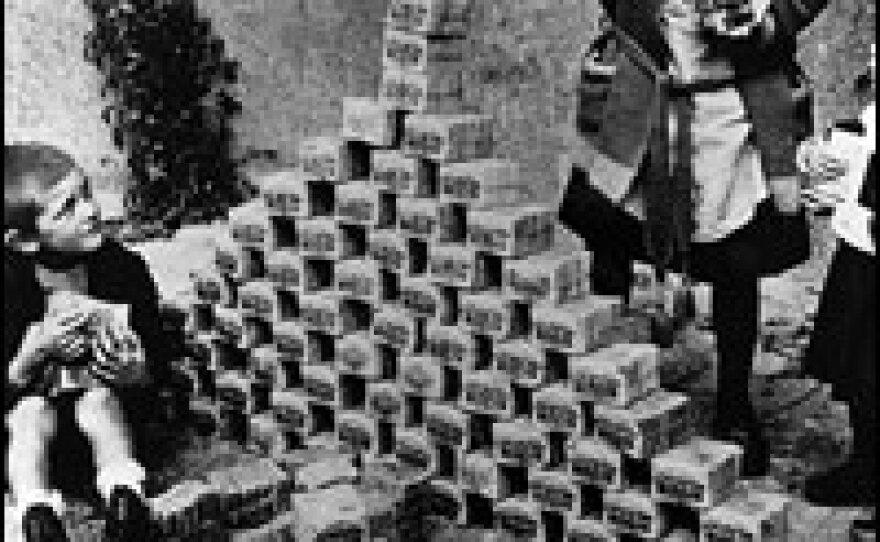

Just after World War I, Germany underwent what is now the textbook case of hyperinflation. Germany had debts to pay and it had gotten into the bad habit of basically printing money. At the peak of the crisis, German currency included a 50-million-mark note.

In When Money Dies: The Nightmare of the Weimar Collapse, Adam Fergusson wrote:

"In October 1923 it was noted by the British Embassy in Berlin that the number of marks to the pound equaled the number of yards from the Earth to the sun. "Dr. Schacht, Germany's National Currency Commissioner, explained that at the end of the Great War one could in theory have bought 500,000,000,000 eggs for the same price as that for which, five years later, only a single egg could be procured."

Some people worry the United States might be heading for inflation soon. The amount of money in an economy is determined by its central bank, which is supposed to be independent of politics.

In the current crisis, the Federal Reserve and other central banks around the world have been taking unprecedented, historic steps to make credit available — to basically push money into the economy.

The head of Germany's central bank has warned that this could lead to inflation.

Merkel earlier this month said, "We must return to an independent central bank policy, and to a policy of reason. Otherwise, in 10 years' time, we'll be in exactly the same situation."

Merkel worried the central banks might be bowing to political pressure, losing their independence.

Josef Joffe, editor of the German newspaper Die Zeit, says concern about inflation is in the German DNA. He worries there's just too much money in the economy.

"[U.S. Treasury Secretary] Tim Geithner and [Fed Chairman Ben] Bernanke and the president and [National Economic Council Director] Larry Summers think they can soak it up again when the time comes," Joffe says. "But meanwhile, they are pumping unprecedented liquidity into the American global system. And I just can only say, 'Good luck, Mr. President, in soaking up that excess liquidity.' And I think that's what Mrs. Merkel reacted to. If the Germans believe in one god, it's the independence of the central bank."

So are we at risk of catching a nasty case of inflation down the road? I took our U.S. economy in for a kind of doctor's office visit to a place that gives this advice out to countries all the time — the International Monetary Fund.

"What we have been telling ... not this country, but all our members, is that there is a need in the short run for macroeconomic policies to support economic activity. But there is a need for every central bank, for every government to have a strategy, to start thinking now about how to exit when the moment comes," says Carlo Cottarelli, the IMF's director of fiscal affairs.

There could be difficulties, he says.

Raising interest rates and pulling money back out of the economy is often unpopular. It's been said the role of a central bank is to "pull away the punch bowl, just as the party gets going." That time is arguably still in the future. As we all know, it's still a pretty lousy party.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))