The election of Barack Obama to the U.S. presidency was celebrated with special fervor by Iraqis of African descent in the southern port city of Basra.

Although they have lived in Iraq for more than 1,000 years, the black Basrawis say they are still discriminated against because of the color of their skin, and they see Obama as a role model. Long relegated to menial jobs or work as musicians and dancers, some of them have recently formed a group to advance their civil rights.

Black people in Basra are most visible at joyous events. When there's a big wedding, Basrawis call in drummers from the district of Zubair. The Basrawi bride and groom are welcomed in traditional fashion by a row of musicians in Arab dress, long dishdasha gowns and red-checkered head scarves. The drummers sway in unison to the rhythms they slap out on broad, tambourinelike drums — and drive up excitement as the newlyweds cross the threshold of a Basra hotel.

The drummers are black men, descendants of the people who came here from East Africa as sailors or slaves over the course of centuries. And while they are welcome fixtures at joyous events all over the city, they say they are not as welcome in Basra's political, commercial or educational life.

Seen As Slaves

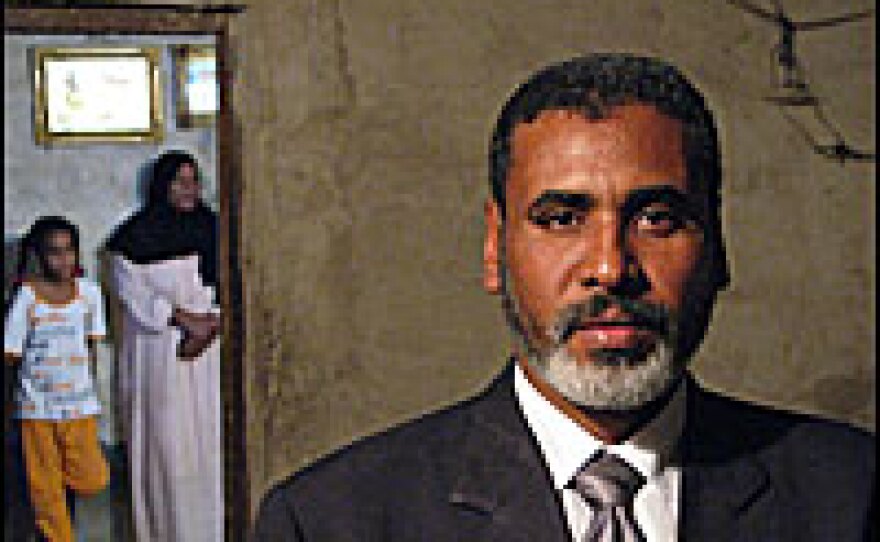

"People here see us as slaves," says Jalal Diyaab, a 43-year-old civil rights activist. "They even call us abd, which means slave."

Diyaab is the general secretary of the Free Iraqi movement. He sits with more than a dozen other men in a narrow, high-ceilinged room in a mud-brick building in Zubair, talking about a history of slavery and oppression that he says dates back to at least the ninth century.

"Black people worked on the plantations around Basra, doing the hard labor, until there was a slave uprising in the mid-800s," says Diyaab. Black people ruled Basra for about 15 years, until the caliph sent troops. Many of the black rebels were massacred, and others were sold to the Arab tribes.

Slavery was abolished here in the 19th century, but Diyaab says black people in modern-day Iraq still face discrimination.

"[Arabs] here still look at us as being incapable of making decisions or even governing our lives. People here are 95 percent illiterate. They have terrible living conditions and very few jobs," he says.

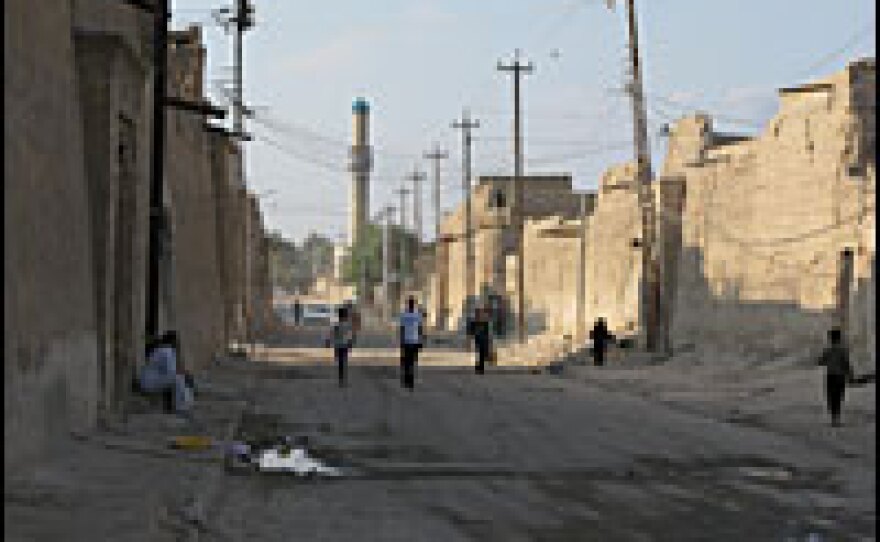

Diyaab takes visitors across the street to a warren of mud-brick courtyards where dozens of people are packed into tiny rooms without running water or sewage. The narrow passageways reek of excrement. Many people sleep in the open yards when the weather is good, because there isn't enough space in the rooms.

"These houses are like caves. This house? This is it," says Diyaab, pointing at a single narrow room and the courtyard outside. He says 15 people, the family of a man called Abu Haidar, live here.

Lightning streaks the night sky as a thunderstorm rolls in from the Persian Gulf. Rain begins to speckle the hard-packed ground. The men gathered around say a heavy rain will flood these rooms ankle-deep with muck and sewage.

Diyaab says there are more than 2 million black people in Iraq. He says they want recognition as a minority, like the Christians, whose rights should be protected. He says his group's demands have been ignored by the Iraqi government, but they have found an ally in a Sunni political party — the National Dialogue Front.

Awath al-Abdan is the head of that party in Basra, and he says he thinks black Iraqis have a strong case for getting their minority status recognized.

"We expect this cause to become a political reality soon because it just started to get publicity. We are working hard to get these people's message heard," he says.

Preserving Their African Roots

For now, the message that most people in Basra hear from the black community is the joy its musicians help bring to weddings. But there's an entirely different feeling when they play for themselves.

The community has preserved many traditions from its African roots, including healing ceremonies that they say call up spirits from their ancient homeland.

On a bright Saturday in Zubair, young men hang bright flags and prepare an altar for a ceremony they say will summon a spirit from Africa. They work under the impatient direction of Baba Sa'eed al-Basri, a prominent local musician. He is the hereditary leader of this religious sect, which combines elements of Islam with African spirit traditions.

The flags, Baba Sa'eed says, represent the African countries associated with various spirits. At the center of the altar is a model of an Arab sailing dhow, the kind of ship that brought black people to this city.

"These rituals," he says, "are inherited self-expressions that were brought to us from Africa, through the ships that traded in this port."

The Baba cleanses the courtyard, by sprinkling it with water. He scents the hands of visitors with a cologne stick and offers tiny cups of bitter coffee. Then he takes his place by the altar, among the candles and incense burners, and tells the drummers to begin.

The ceremony begins with an Islamic invocation, as the drummers chant "there is no God, but God," but soon the rhythm changes. The song says another being is announcing his presence, "a stranger is calling, the sea is calling."

Baba Sa'eed, who has been dancing with his arms and his upper body as he sits by the altar, goes rigid and begins speaking in what he later says was an African dialect, punctuated by phrases in broken Arabic. His voice goes into a weird upper register. The "dialect" has an improvised sound to it, and even the drummers don't seem especially impressed by his spirit possession. He says this place has been blessed, before snapping out of it, with a dazed expression.

The ceremony ends with a song the Baba says will send the spirits back to their homes — retracing the journey that his ancestors made, back through the Gulf to Yemen and then on to the coast of East Africa. The candles and the incense are extinguished. The flags are taken down and the model ship is put away. The black musicians of Zubair pack up their drums and get ready to play another round of weddings.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))