Five years ago, COVID-19 overwhelmed San Diego’s hospitals, pushed health care workers to their limits, and changed the community forever. Since 2020, the pandemic has claimed 6,653 lives in the county. It also exposed vulnerabilities in the health care system.

As experts look to the future, the question remains: How prepared is San Diego County for the next pandemic?

In March 2020, Dr. Juan Tovar was working in the emergency room at Scripps Mercy Hospital Chula Vista.

“We started seeing that this was something we had never experienced before,” Tovar said. “Nothing that we could have done would have been able to prepare us 100% for it. But I like to think we were as prepared as we could be.”

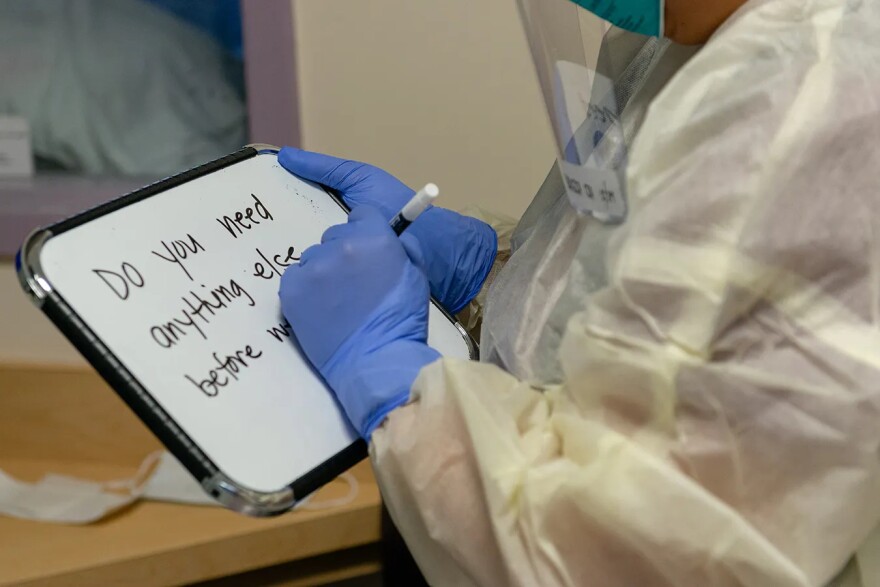

Hospitals had to make rapid adjustments, often treating patients outside or converting non-medical spaces into treatment areas.

“We created examination rooms out of cubbies. We treated patients outside. We set up two tents, we set up a trailer,” Tovar recalled.

Beyond the logistical challenges, the emotional toll on health care workers was severe.

“We saw patients' family members looking through windows at their loved ones dying,” he said. “We had to hold their hands as they were dying because they were alone.”

That trauma led Scripps and other hospitals to create a peer support group to help staff cope.

"Seeing both patients and providers being affected and their lives taken from the virus was scary,” said Dr. James Cunningham, another Scripps Mercy Chula Vista emergency room physician. “I had to make my peace with God and also be okay with my family not being with me.”

He said the uncertainty of those early days made the crisis even harder.

“I think the most challenging part was the unknown and the anticipation,” Cunningham said. “So we started to prepare, expecting that tidal wave of patients.”

Instead of a sudden surge, Cunningham said it was more of a slow rising tide of critically ill patients.

“We also didn't realize as well that people would get sick but stay sick for weeks. And most of the time, a hospital is set up to take care of somebody in a in an acute illness for a few days.”

Adding to the pressure, San Diego hospitals weren’t just treating local patients.

“We knew we were going to be hit especially hard,” Cunningham said. “In Baja California, there’s over 400,000 American citizens who live there. And so a lot of those people cross the border to seek care here.”

The experience pushed Scripps and other hospitals to rethink patient flow and emergency planning, said Dr. Ghazala Sharieff, chief medical officer for Scripps Health.

“We have personally leased some beds with skilled nursing facilities, so that if there's an influx of patients we have a place to discharge patients to,” she said. “Because it's not just people coming in the front door. It's how do we get them out of the hospital to keep the flow going.”

Public health officials are working to detect future threats earlier.

At UC San Diego, researchers are leading a CDC-funded pandemic preparedness project to identify new viruses before they spread.

“So instead of just seeing when people are sick enough to go to the hospital, this program will allow us to know what's actually circulating in the community,” said Marva Seifert, a UC San Diego researcher leading the study’s clinical component.

Sharieff said their data can also help hospitals predict surges.

“Predictive analytics are really helpful, not just looking at the pandemic itself, but also helping us with staffing models,” she said. “So we were able to staff up when we needed to in advance instead of just waiting for the storm to hit.”

She said communication between hospitals and the county has also improved.

“We now have a closer relationship with the county,” Sharieff said. “We know who to call when we need something.”

But even as hospitals are better prepared, the personal impact of the virus remains a challenge.

Psychiatrist Dr. Allen Lee is still experiencing the effects of a 2022 COVID-19 infection. Constant fatigue and other long COVID-19 symptoms forced him to stop working more than a year ago.

“When you're sick and you're tired and then you're trying to access treatment, that's hard enough. And then this is a new illness. The story is being written as we go.”

He said navigating insurance denials and a lack of standardized treatment has been overwhelming. And the biggest problem isn’t just the illness, it’s the lack of recognition.

“Because without awareness, people forget. And then there's no family and friends support which these patients need. There's no funding, which is the fuel for the research and the treatment that's needed,” Lee said.

Until that treatment is found, Lee said he’ll continue to try anything his doctors suggest to manage his symptoms.

San Diego County public health officials say they’ve implemented key lessons from the pandemic, including rapid testing, contact tracing, wastewater surveillance and vaccination campaigns.

Dr. Juan Tovar is optimistic about the county’s future emergency response.

“It feels like we're more of a community now than we were previously. It feels to me like we have something special in San Diego,” he said. “And we came out of this, this very messed up disease state, this, this period, and now we’re doing much better for it.”

Experts agree San Diego is better prepared than it was five years ago, but predicting the next pandemic remains the biggest challenge. For now, hospitals and researchers are watching potential threats closely, hoping their work will give us a head start next time.