Around 1.6 million people across the country are impacted by type 1 diabetes, according to the American Diabetes Association. Salk scientists have uncovered a novel strategy for treating patients with this disease, and say so far the results are promising.

The research is detailed in an August article in the peer-reviewed journal Nature.

Type 1 diabetes typically occurs in adolescents, and it’s a condition where the pancreas doesn’t produce enough of a hormone called insulin. As a result, too much sugar ends up in the blood.

Salk endocrinologist Ronald Evans says there are already a number of effective therapies for Type 1 diabetes, but sometimes the body can reject them, or they have to be partnered with drugs.

“Too much insulin can be lethal, not enough is also gonna be a problem. So you need to measure your blood sugar levels all the time or you need a device that’s stuck in you,” said Evans. “Not ideal.”

He says there are also pancreas organ transplants for type 1 diabetes, but the success of that depends on how well the recipient patient’s body and immune system accepts the organ.

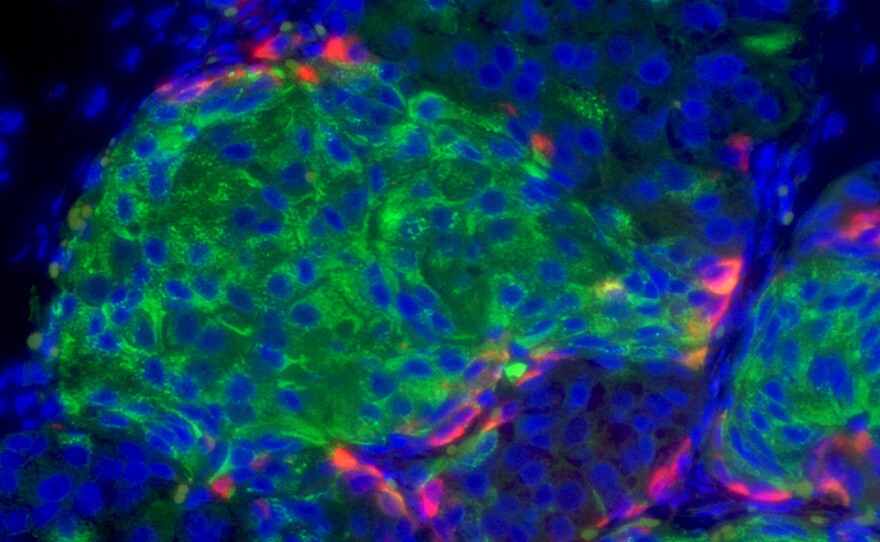

So he and his team came up with a new approach: injectable pancreatic human cell clusters, garnered through stem cell technology, that can produce insulin according to the body’s needs. And they have a type of shielding, which makes them invisible to the immune system, so the body won’t reject them.

“The cells begin to resemble a functioning human cell and we then have a way to turn those cells on and become active, and when we do that we find these cells are able to rescue diabetes in diabetic mice,” Evans said.

Evans said, when they tried the human cells out in mice, the strategy not only reversed the diabetes, it also had long-term promising results.

“The mice aren’t even rejecting the cells so that shows how powerful our shielding mechanism is,” he said.

“We think because of that strong property we might be able to get to human clinical trials much faster, because we appear to have a product that’s very safe and effective.”

Evans says the next big challenge is scaling up the production of these cells, as one patient may need millions of them to receive an effective treatment.