A San Diego company that develops flavors for the food and beverage industry has created a new ingredient that makes sugar even sweeter. And it’s headed to supermarket shelves this fall.

The ingredient’s name: Sweetmyx S617.

In what it called a “commercial milestone,” the local flavor company, Senomyx, announced in an Aug. 28 press release that beverage giant PepsiCo would soon begin adding the new ingredient to two of its soft drinks — Manzanita Sol, nationwide, and Mug Root Beer, in two test markets in the United States.

Sweetmyx S617 is one of the food industry’s answers to our nation’s unhealthy obsession with sugar. The artificial ingredient, one of several similar additives developed by Senomyx, helps food and beverage companies reduce the calorie content of their products by amplifying the sweetness of sugar and other sweeteners.

The upshot: Companies like Pepsi can use less sugar or high fructose corn syrup in their products without sacrificing taste.

While Senomyx’s “sweetness enhancers” could be an important tool to help the nation fight obesity, some scientists and consumer groups wonder how much is really known about their safety.

The ingredients have never been reviewed for safety by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Senomyx, like many other companies that develop food ingredients, has avoided government oversight by using a loophole in a 57-year-old federal law that allows its industry to essentially police itself.

Some scientists critical of Senomyx’s decision to bypass the FDA said the company’s sweetness enhancers have not been adequately studied to determine if they may cause certain health problems.

These scientists aren’t saying Senomyx’s ingredients are unsafe — but they’re worried that there isn’t enough data available to prove that they are safe.

Lisa Lefferts, a scientist at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a Washington, D.C.-based consumer advocacy group, said she analyzed studies completed for four of Senomyx’s sweetness enhancers, including Sweetmyx S617.

“None of the four we examined met the FDA testing recommendations,” Lefferts said. “It’s really a shame that these substances haven’t been tested adequately and that they haven’t gone through the proper pre-market approval procedures, because they really have the potential to help reduce sugar consumption, which would have a wonderful benefit to the public’s health.”

Lefferts and others are especially concerned because these ingredients could eventually become widely popular in American diets — and people would not even know they are consuming them.

Senomyx and PepsiCo said Sweetmyx S617 is safe. In written statements, both companies said the ingredient was properly reviewed by an expert panel of the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association, the trade group that represents flavor companies.

While Sweetmyx S617 has only been evaluated by the trade association, Senomyx notes that many of its other enhancers have also been reviewed by other independent international bodies.

The Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association disputes that Senomyx’s ingredients haven’t been adequately studied. In a written response to questions, the group said that its expert panel “thoroughly reviewed” Sweetmyx S617 and the company’s other sweetness enhancers, which are used in very small amounts in food.

Americans’ sweet tooth

On average, Americans consume roughly 77 pounds of sugar each year.

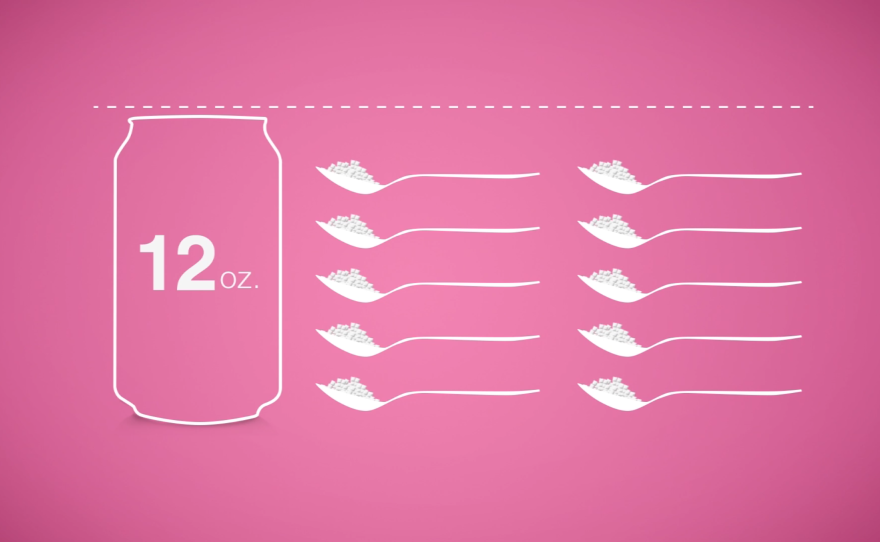

American diets are loaded with added sugars. Sodas like Pepsi and Coca-Cola often attract the most attention. A typical 12-ounce can of regular soda contains about 10 teaspoons of added sugar — more than the American Heart Association recommends adults consume in an entire day.

For years, public health experts have been sounding alarms about the health impact of our nation’s addiction to sugar. Studies have linked sugar-filled diets to a long list of health problems, including obesity, heart disease and diabetes.

In the 1980s, Coca Cola and Pepsi launched diet soft drinks to satisfy consumers who wanted to cut down on sugar and calories. But their popularity has been waning in recent years.

The downward trend can be explained by some studies that have linked diet soft drinks to many of the same health issues linked to regular soda.

There are also growing concerns about the safety of artificial sweeteners like aspartame, which prompted Pepsi to announce in April that it was replacing the ingredient in its diet soft drinks with sucralose, another artificial sweetener.

Paul Breslin, a psychology professor at Rutgers University who studies taste perception, said it’s clear consumers want sugar sweetening their soft drinks — they just want less of it.

“But if you make a soda that has one-tenth the sugar in it, you’re now giving them something that has very little taste,” he said. “The next question then becomes: Can we somehow take the sugar that’s there and give it a little oomph, give it a little boost?”

'A Healthier Way to Flavor'

Senomyx is one of several flavor companies whose scientists are creating ingredients designed to do exactly that.

The La Jolla-based company was started in the late 1990s by three California researchers, including two from the University of California San Diego. It quickly gained attention in the food industry for its development of ingredients that modify the taste of sweet and savory flavors.

Over the years, Senomyx has launched a handful of research programs focused on discovering flavor-modifying ingredients designed to help food companies reduce the amount of sugar, salt and monosodium glutamate, or MSG, in their products without ruining their taste. Along the way, it has established partnerships with major food companies, including Kraft, Nestle and Pepsi.

The company, whose slogan is “A Healthier Way to Flavor,” says its goal is to help the food industry “create or reformulate better-for-you” products.

To accomplish this in the world of sweetened foods and beverages, Senomyx has created chemical compounds that essentially trick the brain into thinking foods are sweeter than they actually are.

By interacting with the taste receptors on the tongue, these “flavor boosters,” as Senomyx calls them, amplify the sweetness of traditional sweeteners. As a result, food companies can maintain their products’ sweet taste despite adding less of the sugar and other sweeteners they traditionally use — potentially saving companies money and consumers calories.

To date, the company has developed a handful of flavor enhancers, including one that amplifies the sweetness of the artificial sweetener sucralose (also known as Splenda) and Sweetmyx S617, which magnifies the sweetness of fructose, high fructose corn syrup and common table sugar.

Pepsi’s two reformulated beverages containing Sweetmyx S617 will hit store shelves this fall. The new Mug Root Beer will be introduced in Philadelphia and Denver, while its reformulated Manzanita Sol, an apple-flavored drink, will be introduced everywhere it is sold in the United States, which is mainly in the Southwest.

Sweetmyx S617 is expected to reduce calories in the two drinks by 25 percent.

“Senomyx has done fundamental research on how we taste sweet things,” said John Leffingwell, a scientific consultant for the flavor industry. “The type of work that they’ve done might get a researcher a Nobel Prize if they were working in a university.”

Leffingwell says Senomyx has invested a lot of time and resources into developing its ingredients.

“It’s been a long hard row because they haven’t made a profit yet, in all these years,” he said. But “All it takes is one big one, and then it could just explode for them. And this might be the one.”

FDA in the dark

When the Center for Science in the Public Interest first learned about Senomyx’s sweetness enhancers about three years ago, the consumer group was excited about the ingredients’ potential to improve public health.

“We got interested in them because they could potentially lead to dramatic reductions in the need for sugar or high fructose corn syrup,” Lefferts said. “So we wanted to see if they were safe, since, if so, that could result in a healthier diet.”

Easier said than done.

In January 2012, Lefferts said the Center for Science in the Public Interest submitted a formal public records request to the FDA, seeking detailed safety data for eight of Senomyx’s flavor-enhancing compounds, not including Sweetmyx S617. The agency’s response: “We have searched our files and find no responsive information.”

All the FDA could provide were exposure estimates for some of the eight compounds, Lefferts said.

“We would have expected the FDA to have boxes of data, all of the safety studies,” Lefferts said. “Instead, they had two pages.”

High-intensity artificial sweeteners such as aspartame or sucralose were added to foods and beverages only after undergoing a thorough, years-long safety review by the FDA. But sweetener enhancers and many other food additives are typically approved as safe through an expedited process without the government’s involvement.

A loophole in a 57-year-old law allows companies like Senomyx to bypass a lengthy, government-led safety review if they can establish that their ingredients are “generally recognized as safe.” In other words, companies using this so-called GRAS process must demonstrate that there is a consensus among qualified scientific experts that their ingredients are safe for their specific use.

Critics of the system said Congress intended only common food additives like vinegar and table salt to avoid FDA oversight. But over the years, companies have exploited the loophole, using it as a quicker way to get new, innovative ingredients to market in the United States.

As the Center for Public Integrity reported in April, many companies hire their own experts — often the same scientists over and over again — to review their additives. But most flavor companies, including Senomyx, have their new ingredients reviewed for safety by a panel of experts with the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association, the industry’s trade group.

The trade association has said that it provides the FDA with all of the data supporting each of its safety determinations — even though it’s not required to do so. But in response to public records requests, the agency has stated that it does not have detailed safety information on flavors approved by the trade association.

Individual companies can voluntarily inform the FDA of their independent safety determinations. These “GRAS notices,” as they are known, include documents supporting the safety status of companies’ ingredients.

In an email, an FDA spokeswoman told inewsource Senomyx has not submitted voluntary GRAS notices for any of its sweetness enhancers.

After failing to get safety data from the FDA, the Center for Science in the Public Interest turned to the trade association. But Lefferts says it took the consumer group more than a year to get safety data for two of Senomyx’s sweetness enhancers, as well as a list of studies that were conducted for two others.

“Information on the identity and safety of substances in the food supply should not be a secret and should not require Herculean efforts to obtain,” the Center for Science in the Public Interest wrote in a January 2013 letter to the FDA lamenting its struggle to get safety data.

In April, a coalition of advocacy groups, including the Center for Science in the Public Interest, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Consumers Union, filed 80 pages of public comments to the FDA arguing that the GRAS system is illegal and asking the agency to institute reforms.

The comments specifically voiced the groups’ concerns about flavor modifiers: “That such complex, novel compounds have been self-determined as GRAS illustrates how industry uses the GRAS exemption to circumvent” the formal food safety process overseen by the FDA.

“I’m not opposed to new technologies. I’m all for it, especially if we can reduce sugar consumption and all of the problems that are in our diet,” said Tom Neltner, an attorney and chemical engineer who has co-authored many reports about the GRAS system. But “There needs to be pre-market review and approval by FDA. Letting them go through the exemption is not what Congress intended.”

Limited testing

With the information it eventually received from the trade group, Lefferts says the Center for Science in the Public Interest began reviewing the safety studies that were completed for four of Senomyx’s sweetener enhancers, including Sweetmyx S617.

The verdict, she says: None of them met the FDA’s testing recommendations.

To be clear, no required tests were missing — just tests the FDA recommends companies conduct for different kinds of substances.

A 2013 study by The Pew Charitable Trusts concluded that it’s not unusual for food additives to be approved without undergoing all of the recommended safety tests. But Lefferts and other scientists say they are particularly concerned about missing studies for sweetness enhancers because they are such novel compounds and because they have the potential to be widely consumed.

An analysis by the Center for Science in the Public Interest found that three of the four sweetness enhancers were missing a handful of recommended tests, including cancer studies, reproduction studies and screens to test how ingredients affect the nervous system. The other enhancer, Sweetmyx S617, appeared to be missing one study on reproductive toxicity.

“If we don’t have studies, for example, on cancer, we don’t know if these substances might cause cancer,” Lefferts said. “If we don’t have a reproduction study, we don’t know if it might affect the ability to conceive normally or have a normal pregnancy. So these are, of course, important things to understand in order to establish that the substances are safe.”

Lefferts and other scientists say they’d like to see sweetness enhancers like Sweetmyx S617 be subjected to testing beyond what is recommended by the FDA, including studies that test their effects on behavior, appetite and weight gain throughout the life cycle.

“We don’t know what the long-term effects are,” said Susan Schiffman, a sweetener expert and professor at North Carolina State University.

Schiffman, who co-wrote a 2008 study on sucralose that was partly funded by the sugar industry, says it’s a good idea to try to develop substances that boost sweetness. But she says the limited testing completed for Sweetmyx S617 is “very, very disconcerting.”

“To put anything into the food supply with this little testing is astounding,” Schiffman said.

Maricel Maffini, a scientific consultant who has co-authored several reports on food additives, says she hasn’t seen any studies testing whether these sweetness enhancers affect the brain.

“So far I have not seen these flavor enhancers tested actually to look at the brain — if there is any changes to the chemistry of the brain, how the brain reacts to them,” she said. “And that is one of the reasons I am a little concerned about their use.”

‘Robust safety testing’

Senomyx, PepsiCo and the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association all declined interview requests for this story. In written statements, however, all three said Sweetmyx S617 was properly evaluated and that it is safe.

“Senomyx’s flavor ingredients go through robust safety testing before they are added to foods and beverages,” Senomyx said in a statement.

In addition to being reviewed by the flavor industry trade group, the company noted that many of its ingredients have been independently reviewed for safety by international bodies, including the Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives, an organization affiliated with the World Health Organization of the United Nations, and the European Food Safety Authority.

“If you turned it over to the FDA,” John Leffingwell said, “20, 25 years from now, you might get a result from them.”

To date, Sweetmyx S617 has only been approved by the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association, also known as FEMA.

“All candidates for FEMA GRAS status are thoroughly reviewed by the FEMA Expert Panel applying the Expert Panel’s well-recognized, widely accepted, and published safety evaluation criteria,” John Cox, the trade association’s executive director, wrote in response to questions. “All FEMA GRAS flavor ingredients are safe for addition to foods and beverages.”

Cox disputes that the four sweetness enhancers analyzed by Lefferts were missing studies. He also says they have been reviewed to see how they may affect the brain.

“Studies included in FEMA GRAS evaluations routinely include parameters relevant to an assessment of ‘possible effects on brain chemistry’ and no effects were seen for [Sweetmyx S617] and other similar substances,” Cox wrote.

Leffingwell, the flavor industry consultant, says the trade association is more than capable of handling safety assessments for ingredients like Senomyx’s sweetener enhancers — especially because they are used in such small amounts in food. Besides, he says, the FDA doesn’t have the resources to conduct safety reviews for all new ingredients in a timely manner.

“If you turned it over to the FDA,” Leffingwell said, “20, 25 years from now, you might get a result from them.”

‘Clean’ labels?

Shoppers can identify well-known artificial sweeteners like aspartame and sucralose by scanning ingredient labels. But they won’t be able to spot Senomyx’s sweetener enhancers so easily.

Instead of being listed individually by name on ingredient labels, Pepsi is expected to list Sweetmyx S617 under the broad category of “artificial flavors.”

“Since Senomyx flavor ingredients are part of a proprietary blended flavor mix, they are not individually listed on the ingredient statements of foods and beverages,” Senomyx stated.

In 2005, Senomyx’s chief executive told The New York Times that it was “helping companies clean up their labels.”

Lefferts and other scientists say categorizing sweetener enhancers as “artificial flavors” is misleading. After all, they say, many sweetener enhancers have no flavor of their own. They merely enhance the flavor of other sweeteners.

“To put anything into the food supply with this little testing is astounding,” Susan Schiffman

FDA regulations state that “The term artificial flavor or artificial flavoring means any substance, the function of which is to impart flavor.” On its website, Senomyx states that its “flavor boosters don’t provide a sweet taste on their own.”

“Sweetness enhancers should not be permitted to be considered artificial flavorings for the purpose of labeling,” the Center for Science in the Public Interest wrote in a March 2013 letter to the FDA. “Importantly, we believe that consumers would like to know when their taste buds are being influenced or manipulated by novel ingredients.”