Diana Juarez was watching TV on a Sunday evening when she smelled something burning.

Juarez lives right behind the post office in Niland, a small town in north Imperial County. She walked outside and saw flames rising above the roof of the building.

Juarez called 911. Then she and her childhood friend, Nellie Perez, stood and watched the post office burn.

“We stood there and we waited, and we saw the fire trucks come,” Juarez, a former postal worker, said.

That was in February 2022. Two days after the fire, the U.S. Postal Service put out a notice saying the post office would be closed temporarily. They said customers could pick up their mail in neighboring Calipatria for the time being, and officials would reopen the post office “as soon as it is safe to do so.”

But two years later, residents still have not received any concrete updates on when they will see the Niland Post Office return.

Instead, community leaders said the closure has forced some residents to drive 50 miles to pick up their mail and delayed deliveries of medication and groceries to a majority low-income community.

The Postal Service declined requests for an interview. In a statement, a spokesperson said USPS was committed to finding a new facility and continuing to serve the area.

Niland, a town of around 500 that sits at a bend in the road along State Route 111, had joined the ranks of countless small communities fighting post office closures nationwide. In 2011, the Postal Service nearly shuttered thousands of post offices in rural areas across the country, but backed off after a national outcry.

Niland residents said the closure has fallen especially hard on their town because it has been steadily losing businesses and infrastructure. Decades ago, Niland was a hub for tomato farming in the valley and had a close-knit Filipino community. But the number of people living in the town plunged in recent decades, forcing salons, restaurants, banks and libraries to close their doors.

Now, residents are fighting to bring their post office back.

“We have many that are elderly, we have disabled,” said Anna Garcia, a longtime Niland resident and member of the community advocacy organization NorthEnd Alliance 111. “The mail is very important to them. It carries their life.”

Losing a lifeline

The Niland Post Office had been a fixture in northern Imperial County for more than a century when it burned.

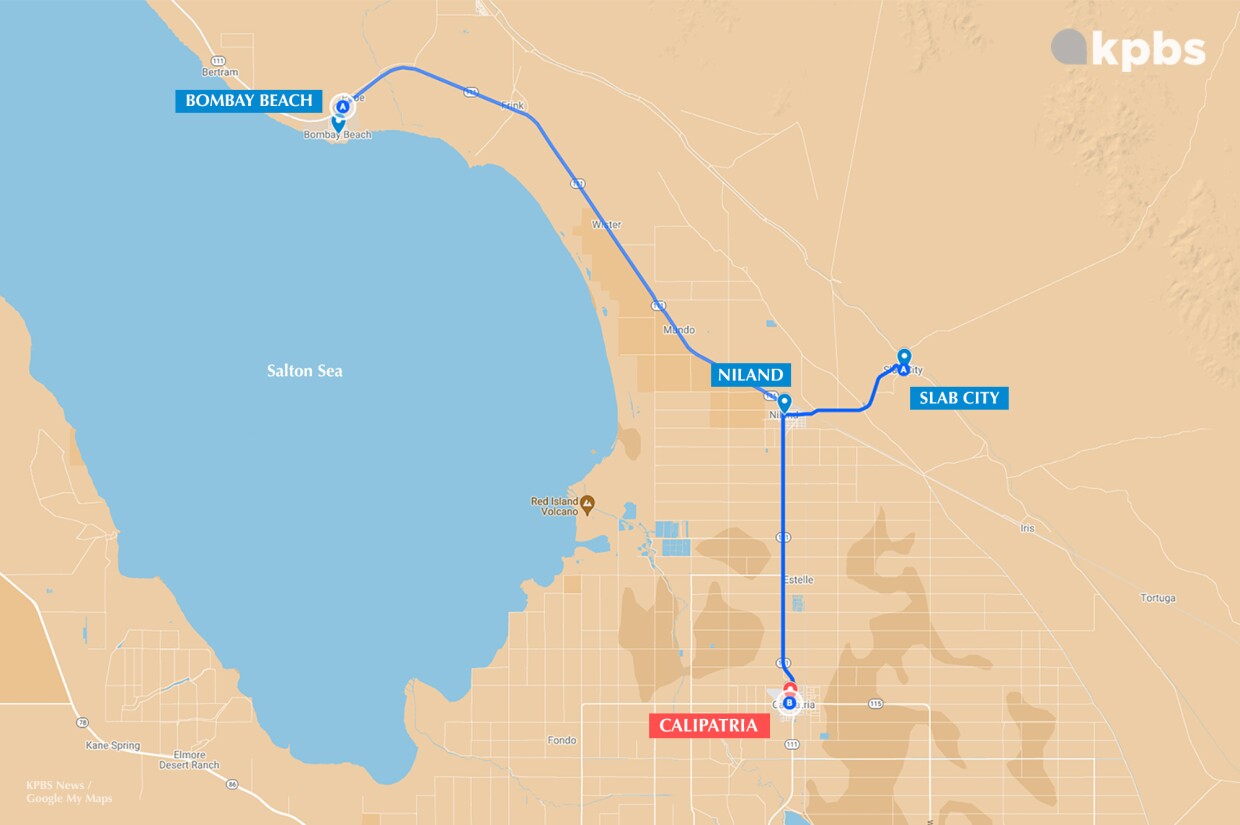

In addition to Niland, it served Bombay Beach, a former waterfront resort town further north, and Slab City, an isolated desert community of squatters and artists to the east.

From the beginning, there were problems with the Postal Service’s stop-gap measure to reroute the mail through Calipatria.

“There was chaos with us receiving our mail,” said Andra Dakota, who also lives in Niland. “People would receive mail that is addressed to other people, would be missing their mail — including my very own personal mail, like bank statements and medical records.”

Dakota said she didn’t blame the Calipatria post office, guessing that the disruptions were a result of the sudden influx of new mail.

The distance was another challenge. From Niland, Calipatria is only a 16-mile round trip. For residents of Bombay Beach though, it is more than 50 miles and an hour-long drive. Slab City residents have a longer drive too, although not as much.

Even for Nilanders, community leaders said it was a struggle to make that trip, partly because more than half of all residents in the town count as low-income, according to census data.

“I know so many people that don't have vehicles,” said Juarez, who is also a member of NorthEnd Alliance. “I know so many people that are elderly. And if it's frustrating to me — and I have a way — I can’t imagine those people that don't.”

A year into the closure, the Postal Service started sending a mail truck to Niland three days a week, where residents could come pick up their mail. That helped ease the hardship, but it wasn’t a full replacement since the truck was only there certain weekdays and for just a few hours in the middle of the day.

At the same time, the Postal Service and community members have been looking for a building to replace the post office.

Last year, NorthEnd Alliance members went to ask the Calipatria Unified School District, which also serves Niland, if they had any properties available.

The school district had also been feeling the loss of the post office. Superintendent Angelita Ortiz said the elementary school in Niland wasn’t able to receive mail regularly and that staff had been driving back and forth to collect it from Calipatria.

And it turned out the district did have a potential building in Niland: a vacant preschool that had been donated to the district. The building was in working order, although district officials said the Postal Service would likely need to renovate it to meet the needs of a post office.

However, those negotiations have dragged on as USPS and district officials struggled to agree on the terms of a potential contract.

USPS spokesperson John Hyatt declined to discuss details of the negotiations. In an email, Hyatt said the agency was working “diligently” to find a suitable location to restore services to Niland.

Staff members for U.S. Sen. Alex Padilla (D-Calif) and U.S. Rep. Raul Ruiz (D-Palm Desert) did not respond to requests for comment. Imperial County Supervisor Ryan Kelley also did not respond to an interview request.

In February, residents took things into their own hands again, organizing a protest to call attention to the post office closure. More than a dozen community members rallied outside the burnt building with colorful signs, demanding a concrete commitment from the Postal Service on when they will restore full service.

“We want to bring a spotlight to us,” Garcia said, who also worked for many years at the post offices in Niland and Imperial. “We want people to know that we are important. We do matter. All mail is important.”

Decades of change

Niland’s main street was already a lot quieter than it used to be, even before the post office closed down.

For decades, the town was a farming community home to many Filipino families, as well as immigrants from Mexico and Eastern Europe. In the 1960s, Niland’s culture revolved largely around the region’s thriving tomato farms, which residents would celebrate with an annual Tomato Festival.

“It was just a good little town,” said Juarez.

The highway, the railroad and the nearby waterfront towns also brought a flow of workers and truckers through, along with celebrities like Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby. The town’s vibrant history has inspired a newsletter called Niland’s Tomato Vine, an annual reunion for current and former Niland residents and an ongoing oral history project.

But the ensuing decades were hard on Niland. As the federal government began loosening its rules on trade with Mexico, many of the town’s small tomato farms collapsed and went out of business.

“They just could not compete,” said Benny Andrés, author of the book ‘Power and Control in the Imperial Valley’ and an associate professor of history at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. “And so Niland started to sort of decline because you didn’t have a local base of people who were buying locally.”

As those residents moved away, Andrés said, shops began to close. The beauty salon run by Garcia’s sister, the Chevron gas station, the bait shop, Bobby D’s Pizza — even the public library.

Garcia and Juarez also remember things changing as tourism at the Salton Sea dried up, traffic shifted to the other side of the lake and many kids who grew up in Niland moved away.

The drying of the vast inland sea has exposed Niland and other areas to new hazards from farmland pollution, military weapons testing and other sources. Many communities along the sea report much higher rates of asthma and other health conditions.

Niland has seen other devastating environmental disasters too. In 2020, a ferocious wildfire leapt from the highway and swept through the town, destroying dozens of homes and displacing more than 100 residents. This past January, water spilled from a nearby canal and flooded the streets.

The discovery of vast lithium reserves under the Salton Sea has brought new optimism to the town in recent years. Energy companies are already negotiating the early stages of an operation that researchers estimate could be worth billions of dollars.

Many residents hope the lithium industry may be a turning point for the North End. Experts have said the race to tap the valuable mineral could be an economic boom for the Imperial Valley, and Niland is one of just two communities on the front lines of the planned lithium extraction zone.

But some worry that the disparities Niland faces now will remain. Garcia points to the post office situation as a troubling sign.

“Niland is one of the fence-line communities for Lithium Valley,” Garcia said. “But as you can see, you wouldn't even be able to receive your mail here. What does that say?”

Still, like many community members, Garcia is also hopeful about the future of the town. One dream of NorthEnd Alliance, she said, is to revive that old Niland spirit for all of the children who have moved away.

“We'd like to bring our town back so that they will see that there is a life here,” she said. “So that it can be a place where you are proud to say you're from Niland.”