Female genital mutilation doesn’t just plague millions of women in Africa, the Middle East and parts of Asia where it’s still practiced.

Long-term medical and emotional problems caused by the procedure, which is recognized as a human rights violation by the World Health Organization, are also experienced in the U.S.

Thousands of women who live in the U.S. as refugees or immigrants were genitally mutilated as young girls in their home countries. San Diego County, which accepts more refugees than any other part of California, has one of the largest populations of these women – including the nation's second largest Somali community.

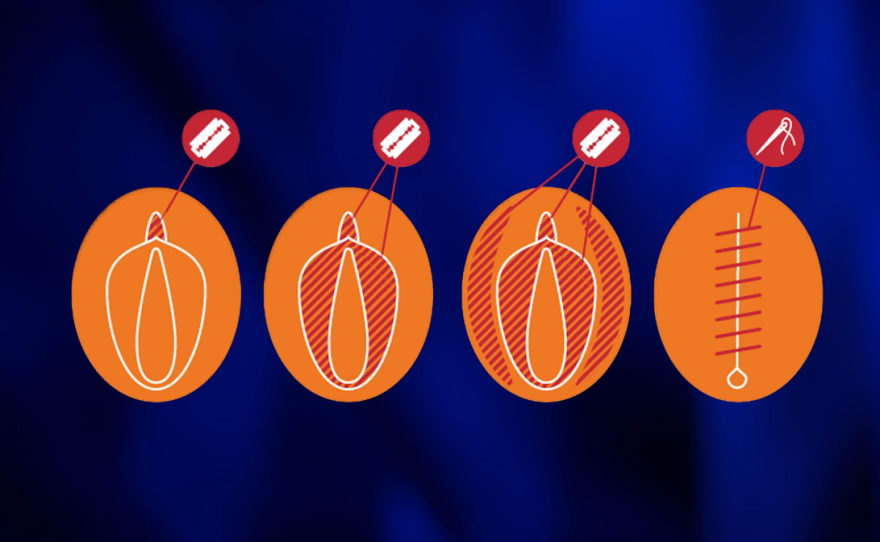

The procedure can range from partial removal of the clitoris to extraction of the entire clitoris, all labia and stitching the vulva shut.

Years later, these women can suffer medical problems. They are often susceptible to infections. Sometimes, they develop life-threatening vaginal cysts caused by repeated damage to their scar tissue. Scar tissue doesn’t stretch like healthy skin, so childbirth, sexual intercourse and even just walking around can cause extensive damage.

For women with the most severe mutilations, urine and menstrual blood can get backed up inside them. Childbirth can require cutting open the closed area or resorting to C-sections. Sexual intimacy is fraught with complications.

Often, these women suffer in silence because it’s taboo to talk about genital mutilations in their circles. Some refuse to seek help out of shame.

“It’s culture. Even living in this country, Western world, 21st century, still they believe, ‘I don’t want to talk about it, or if I talk about it, it’s outrageous,’” said Maha Hussein, a 42-year-old Somali refugee.

Hussein has suffered infections and bleeding for years. A cyst formed where her clitoris once was. As it grew to the size of a tennis ball, it began to displace her urethra, interfering with her ability to urinate. Hussein decided to seek help, and agreed to let KPBS document her process.

“I’m developing more serious medical problems,” Hussein said. “There’s no reason to hide anymore. I’m breaking the taboo.”

Hussein recalls her mutilation

Hussein was five years old when her grandmother took her to a local hospital in Somalia for a routine genital mutilation. Hussein’s mother — a women’s rights activist who opposes genital mutilation — was out of town.

“They gave me local anesthesia, and then the circumcision took place,” Hussein said.

In the sterilized hospital environment, a trained midwife removed her clitoris and labia, then stitched her vulva shut, leaving only a small opening from which to urinate.

“After the anesthesia was out of my system, I was feeling very bad — the burning inside,” she recalled. “And I ended up three, four days not urinating at all until my abdomen was swollen and I had a high fever — 104, 105.”

She was throwing up, her pulse pounding in her head. Her grandmother took her back to the hospital for antibiotics. The agony subsided.

Hussein regained a semblance of normal life. In fact, it was easier for her in some ways. Her earliest memories are of the bullying she endured at school because she was not yet mutilated. “You’re not ‘daher.’ Daher means clean. Pure,” Hussein said.

Before the mutilation, older girls pinned her down and forced her to show them her “unclean” parts. After the mutilation, the bullying stopped. But then puberty came, and with her periods, a new and permanent suffering.

Why parents do this to their daughters

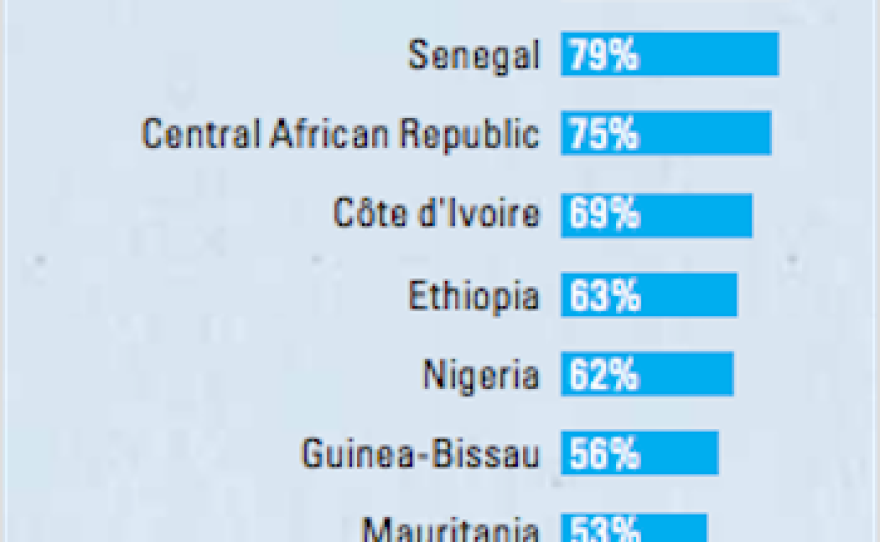

Female genital mutilation is practiced in 30 countries, but it is declining due to international campaigns against it, said Gerry Mackie, co-director of the Center on Global Justice at UC San Diego.

In Hussein’s Somalia, more than 98 percent of women between the ages of 15 and 49 have been subjected to it, according to UNICEF. But the data, drawn from reproductive health surveys, don’t reflect recent declines in the procedure. Female genital mutilation is usually done to girls before they reach puberty, not to women of the reproductive ages surveyed. Recent declines would be reflected in the youngest girls.

Campaigns against female genital mutilation, such as UNICEF’s “Saleema” in Sudan, could cause the practice to disappear in the next 20 to 30 years — about the time it took foot-binding to stop in China following the dawn of campaigns against the practice, Mackie said.

“Saleema” means whole or uncut, which UNICEF promotes in association with a brand of swirling colors. One video promoting "wholeness" shows women transforming from shadows to colorful figures over time.

Before “Saleema,” the Sudanese word for an uncut woman was the equivalent for “slave prostitute.”

Mackie explained: “To be uncut means to be an un-marriageable girl."

Vilifying the perpetrators doesn’t discourage female genital mutilation, he said, because the parents who subject their daughters to it usually don’t mean to harm them.

Until recently, marriage represented the apex of female success in many of the countries where genital mutilation is practiced. Female genital mutilation made it possible for women to find husbands.

“It becomes a sign of honor, modesty, chastity, fidelity,” Mackie said.

Highlighting the medical problems that result from female genital mutilation doesn’t stop the practice, either, he said. It only results in the medicalization of the procedure. Parents start taking their daughters to trained medical professionals, as in Hussein’s case, instead of doing the cutting themselves.

Campaigns against the practice are effective only when they focus on collective action for everyone’s benefit, Mackie said. Groups of men have to announce they’re willing to marry intact women, and groups of women have to speak out in support of their daughters’ human rights.

A recent UNICEF report Download Acrobat Reader shows a significant decline in support for female genital mutilation in countries where such campaigns have been implemented. In Somalia, initiatives by the Elman Peace and Human Rights Centre have helped reduce gender-based violence in general.

In the meantime, women who were already mutilated must deal with the consequences.

‘I’m not (a) complete woman’

Hussein came to San Diego as a refugee in 2001, leaving behind warlords who threatened her life. But her mutilation continued to plague her.

“I’m not (a) complete woman. I’m half,” she said. “I’m missing something in my life. Sexuality is a gift from God. And you’re missing that one? It’s like you’re a toy. A toy has no feeling.”

She fell in love with a man named Bille Nur, a fellow Somali refugee.

In Somalia, Hussein witnessed men abandoning their wives because of problems tied to their mutilations. A common post-childbirth problem was the fistula, a hole between the vagina and rectum that diminishes bowel movement control. Hussein recalls comforting countless women who experienced the double calamity of heartbreak and grave physical injury.

Nur was different. After they married, whenever she was too sick to move around, he helped her bathe, carrying her around the house, and bringing her medicine.

“I love my children, I love Maha, I love my family,” said Nur, who works at a San Diego bakery. “I don’t have no intentions to leave nowhere.”

He was not surprised when he discovered Hussein was mutilated. His six sisters underwent the procedure as little girls. It was normal to him. But seeing his wife go through the agony of childbirth opened his eyes to its horrors.

“What she went through, it’s a wake-up call to the world to stop mutilation,” he said. “It’s inhumane.”

In Somalia, Hussein was a woman’s rights activist, like her mother. She sought a degree in health care administration, and helped educate and protect women against HIV. Today, she works as an elder care provider and community advocate in San Diego. She has five U.S.-citizen children, including a four-year-old girl, Sagal, who will never be mutilated.

Nur said he is glad his wife is seeking help for her complications.

“Her health is really mine. I really value as mine. I want to see her healthy,” he said.

Hussein said if it weren’t for the support of her husband and friends, she would be taking medication for anxiety or depression.

“I felt one way I was tortured, but from the other side of the world, I got a gift,” she said.

Seeking help

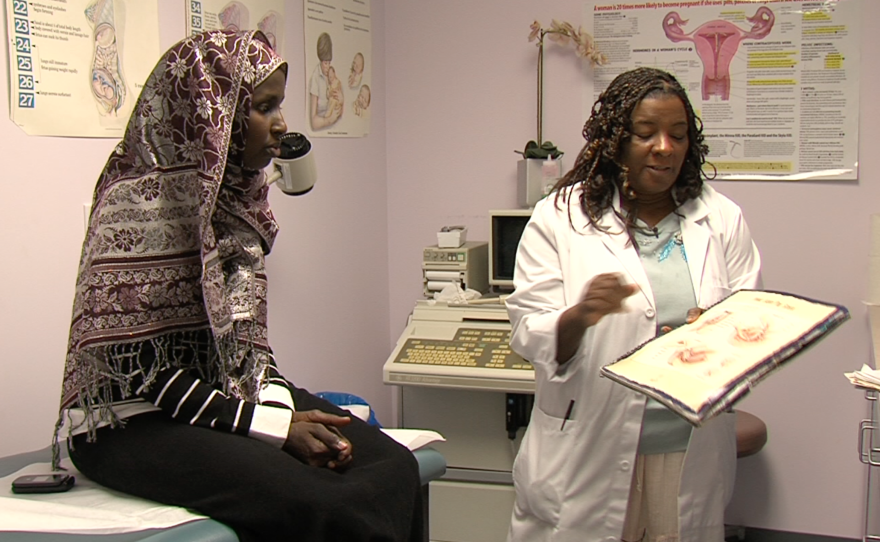

On a recent Tuesday, Hussein visited her obstetrician and gynecologist, La Tanya Lee, who explained that Hussein’s growing cyst could be life-threatening because it was displacing her urethra.

“If you can’t pee, everything could back up into you, and send you into renal failure, you could die just from that, OK?” Dr. Lee said.

She planned to remove the cyst surgically later that week, and repair some of the scar tissue causing Hussein so much pain.

Dr. Lee said many of the women who come to her do so with reluctance. They’re embarrassed, or don’t think U.S. doctors have any relevant expertise. Dr. Lee admits she didn’t at first.

“I remember the first time I saw it, I was like, ‘what the heck?’” she said.

But she said U.S. doctors are growing accustomed to it and to treating its complications. Dr. Lee said she wishes more of these women would seek help when they need it.

Hussein said she knows the importance of seeking help because of her background in health care. But countless women in her situation refuse to see a doctor.

One woman dies

Hussein’s best friend, Fatima Abdelrahman was mutilated as a 7-year-old in Sudan.

“If we refuse in that time, or if we run, they get us from wherever we go,” Abdelrahman recalled.

She said her mother, Halima, died of complications that started like Hussein’s cysts. She refused to seek help until it was too late.

“Some women like her age, they respecting their culture,” Abdelrahman said.

She said she thinks her mother would still be alive if she had sought help early. But she didn't want to because of the taboo.

Abdelrahman said her own genital mutilation caused her serious problems during her seven childbirths, which had to occur through C-section, and led to repeated infections.

She said she sought help each time she developed an infection. But she isn't interested in surgery to lessen the pain and discomfort she experiences from daily movement. She feels she's already had too many surgeries. Additionally, if it isn't life-threatening, she said: "It's shame for me to fix (it)."

Demonstrating a mutilation ritual

A few days before her surgery, Hussein brought her 4-year-old daughter, Sagal, to Abdelrahman’s house.

The two friends wanted to demonstrate a female genital mutilation ritual, without harming Sagal.

Abdelrahman had decorated her living room in the Sudanese tradition, with burning incense, ornate rugs, floating drums, and a single twin-sized bed.

“You look beautiful, Sagalina,” Abdelrahman cried, leading Sagal to the bed.

Sagal wore a white dress, her dark curly hair pulled back in braids. Abdelrahman placed a crown of golden beads on Sagal’s head, then a necklace of brown seeds around her neck.

“Wow, this is gift for you, OK?” Abdelrahman told Sagal.

She explained that the ritual is a sort of coming-of-age party. Friends and neighbors come over to dance and sing, trying to make the girl feel special and happy. After showering the girl with gifts, they stain her fingertips with henna mud.

Molding the mud around Sagal’s fingertips, Abdelrahman said, “If you keep it, your hand become like my hand.” Her own fingertips were colored dark brown.

Abdelrahman let out a loud whoop, as is customary in the ritual. “That’s so loud!” Sagal cried, squirming.

Eventually, the girl is placed on the bed, on a round stool.

One woman stands behind her, pinning her down.

“The other one grab one leg, and the other grab another leg, so she’s not crying and not screaming and not moving,” she said.

Then the mutilation would take place. Abdelrahman showed us the different blades that have been used throughout history — from sharpened stones to scissors.

“She sharp it very nice, and she put it like this in skin, and she push it and cut like this so when she cuts, she cuts everything out,” she said.

‘A blow for freedom’

On Aug. 5, at around 8 a.m., Dr. Lee slowly cut away at Hussein’s cyst at Sharp Chula Vista Medical Center.

“Oh yes, that’s a blow for freedom,” Dr. Lee said.

Hussein remained awake for her procedure. She lay on the operating table, anesthetized from the waist down, her expression flickering between smiles and grimaces of fear.

After about an hour, Dr. Lee finished removing the cyst, about 3 inches long and 2 inches wide.

“Everything went well,” she said after the surgery. “I dissected out the cyst and got rid of some of the extra tissue that was covering the cyst and sort of pulled together some of the underlying muscle tissue to make her a plastic clitoris."

She said it would take Hussein six to eight weeks to heal.

“I’m sorry you have to go through all this,” one of the nurses told Hussein as she wheeled her out of the surgery room.

“It’s all right, ignorance causes such problems,” Hussein said.

In the recovery room, Hussein was reunited with her husband.

“I feel much better,” she said, clasping his hand. “Confident.”

“I’m relieved,” he said. “I’m grateful.”

Hussein hopes her story encourages other women to seek help.

“It’s good always to diagnose early, before it’s too late,” she said. “They can be helped.”