First Of 2 Parts

Michelle Carpinelli looks like she has it all.

She has a beautiful home in Vista. A loving family with four children.

But ever since the 52-year-old Carpinelli was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2010, she’s been put through the wringer.

She’s had a mastectomy, a hysterectomy, radiation, and numerous cycles of chemotherapy.

Then a little over a year ago, Carpinelli experienced a different kind of pain.

“I had pressure in my forehead and headaches, and just before my operation I had blurred vision in my right eye,” Carpinelli recalled.

Doctors discovered Carpinelli had a brain tumor. She decided to go to Ohio's Cleveland Clinic to get it taken care of.

Carpinelli thought the procedure went well.

“When I woke up, there was hardly any pain, my headaches subsided, and my blurred vision was gone,” she said.

But recent scans reveal Carpinelli now had another, larger brain tumor. It was so close to the original one, that doctors aren’t sure whether it’s scar tissue, or a separate growth.

So Carpinelli was facing another trip to the operating room.

She said even though she’s had brain surgery before, “You still feel a little timid. You know, it’s your brain. They’re gonna open you up, you never know what’s gonna happen. But I have faith in Dr. Chen."

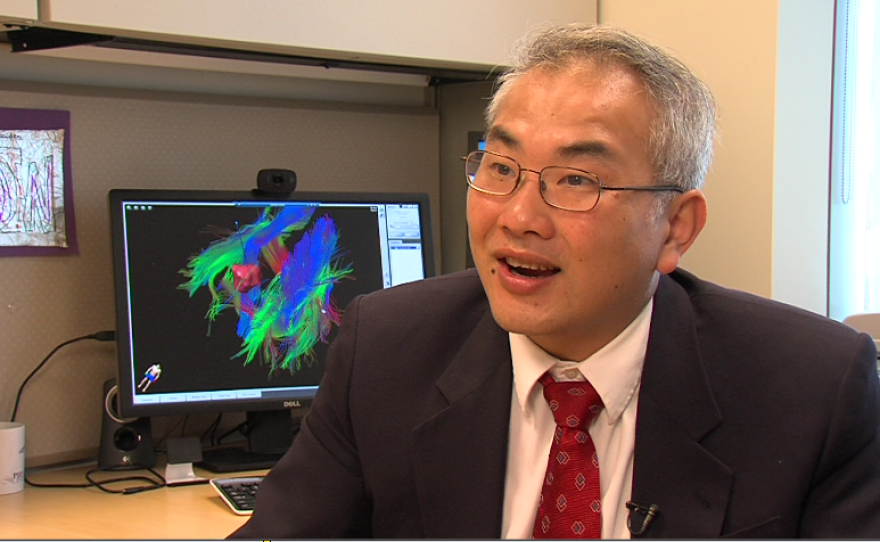

Dr. Clark Chen is Carpinelli’s neurosurgeon and vice chairman for the UC San Diego Health System. In his office at UCSD Moores Cancer Center, Chen described the combination of groundbreaking imaging tools he uses to plan his surgery, including those unique to the Moores Center.

In fact, Chen is the only neurosurgeon in the world using a combination of next-generation surgical tools along with these advanced imaging techniques as his standard of care.

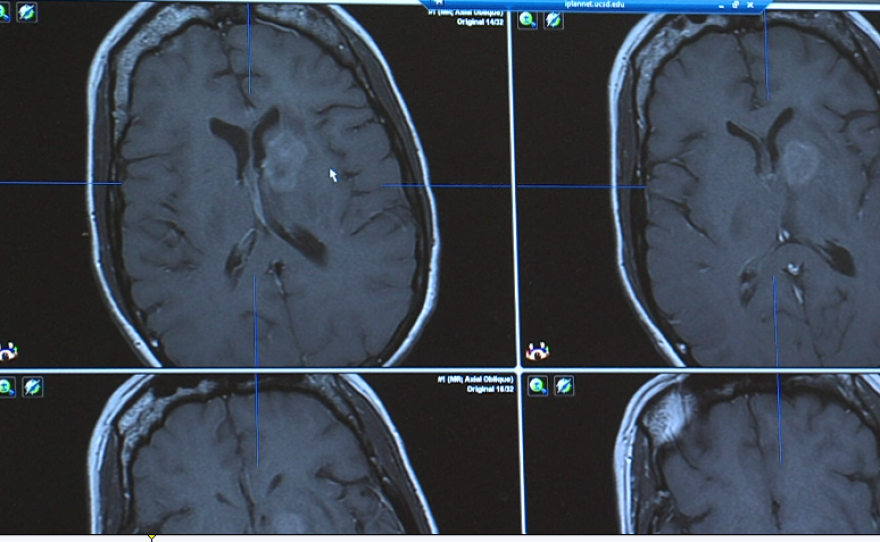

He starts with an MRI of Carpinelli’s brain.

“So what you can see with a conventional MRI is that there’s a region of abnormality that seems brighter than the rest," he said, pointing to his computer screen. "And this, to us, is very worrisome, for a metastasis, or a form of breast cancer that went to the brain.”

The tumor is very deep, near the center of the brain.

Chen explained the MRI displays only the barest outlines of the tumor and the brain itself. If he were to rely on this image alone to guide him, it would be like operating in the dark.

But thanks to a 3D imaging technique called tractography, Chen can superimpose the neural connections in the brain that surround the tumor.

“And so by looking at this and studying this carefully, a neurosurgeon can get a sense of where the tumors are, where the tumor is located, where the key tracks are located, so that in our mind, we can identify a trajectory that gets to the tumor, without severing any of these tracks," Chen said.

Using these images, Chen is able to chart the safest path to reach the target.

One image shows a rendering of the patient's brain, with a thin blue line extending from the top of the skull to the tumor.

“You see there is a blue line, and that defines how I’m going to get to the tumor. And as you rotate this around, you will see that that trajectory in no way intersects any of these critical tracks in the brain,” he said.

Chen will perform the surgery inside an MRI suite, so he can get real-time images of Carpinelli’s brain. But because of the intense magnetic field in the MRI machine, all of the surgical instruments must be made of plastic.

After a small hole is drilled in Carpinelli's skull, Chen will place a special frame around the entry point. Next, he’ll attach what’s called a controller to the frame.

“Now, you know that with the MRI, the space is very small, so this is actually far away from the surgeon," Chen explained. "So in order to access the controls, we have these controllers that basically serve as extenders. And these are inserted into these grooves.”

When everything is in place, and the images confirm that Chen has found the right pathway to the tumor, he’ll use a flexible laser probe to destroy it.

Chen said when he first saw the neural structure of the brain displayed on his computer, he knew it would be a game changer for neurosurgeons.

“We spend our lives dedicated to neuroanatomy. We do dissections, we visualize, we use computer simulations in order to appreciate and understand where these tracks are. And to see that in real life, it’s the face of God,” he said.