A trend toward giving children fewer shots at one time, combined with continued skepticism about vaccines’ safety, means more kindergarteners than ever in San Diego County were not fully immunized when they started school last year.

Much has been made of the “personal belief exemptions” parents use to allow their unvaccinated children to attend school. But a movement to delay or spread out vaccines for children is also lowering the county’s immunization rates for kindergarteners.

Nearly 90 percent of the county's schools had kindergarten classes with at least one student who was not up to date on vaccines at the start of the 2012 school year, the most recent year data was available from the California Department of Public Health.

California law requires students to be vaccinated against diseases like polio, measles and whooping cough before they can attend school. But parents can skip these requirements by signing a personal belief exemption, or PBE, which says immunization is contrary to their beliefs. (At the end of the year, a new state law will also require a health care practitioner's signature on the exemption). Just less than 4 percent of San Diego County kindergartners entered school last year with a PBE on file.

Even more children, about 5.4 percent, received conditional exemptions. Most vaccinations are given as a series of doses, and conditional exemptions mean kindergarteners have had some, but not all of the doses required to attend school. Children who aren't completely up to date on their vaccines but are working toward full immunization can attend school with a conditional exemption.

While there are many reasons for conditional exemptions — children have switched doctors or health care plans, missed appointments or haven't turned in vaccine records — some parents are choosing "alternative vaccine schedules," said Karen Waters, chief of epidemiology and immunization services for San Diego County's Health and Human Services Agency.

This means parents delay or spread out vaccine doses, so their kids aren't fully immunized when they start kindergarten.

Alternative vaccine schedules have grown increasingly popular in the last few years and seem to offer a "middle ground" between anti-vaccine parents and those who follow the state's vaccine schedule.

But the trend concerns medical experts.

Because vaccines do not become completely effective until a child has received every dose, they say. Children on a delayed schedule aren't fully protected when they start school, posing an increased risk of disease outbreaks.

Vaccines' 'Middle Ground'?

One alternative vaccine schedule was made popular by Orange County doctor Robert Sears in his 2007 book, "The Vaccine Book: Making the Right Decision for Your Child."

"This is not an anti-vaccine book," Sears wrote. "…As I see it, vaccination isn't an all-or-nothing decision."

Instead, Sears, who goes by Dr. Bob, recommends a schedule that gives no more than two vaccines at a time (and no more than one aluminum-containing vaccine at a time) to spread out exposure to chemicals and limit potential side effects. He also admits, "we don't know if giving six simultaneous vaccines causes more side effects," but said giving fewer is "a reasonable precaution."

Sears's schedule has prompted fierce debate, including responses from respected pediatricians and scientists who say the schedule is not based on any science and would only end up harming more children.

The Dr. Bob schedule means children aren't finished with their first set of shots until they're 8 years old.

This means Sears-following children won't meet state vaccine requirements when they enter kindergarten. Sears helps parents prepare for this, writing, "All states … allow parents to waive vaccines for religious reasons. Sure, the school will hassle you and give you the 'bad parent' speech, but legally the administrators must let your child in."

Some parents following alternative schedules could be submitting personal belief exemptions to avoid being hassled by schools. Others could be choosing conditional exemptions. The state data doesn't show parents' reasons for taking exemptions so it's impossible to know exactly how many San Diego families are following alternative vaccine schedules.

'It's A Gut Feeling'

Carolyn Olstad sits in a grassy park across the street from her San Marcos home watching her two sons eat crackers and bury toys in a sandbox.

Olstad isn't anti-vaccine, but wants to slightly delay shots for 1-year-old Parker and 3-year-old Grayson. So instead of getting multiple shots in one doctor's appointment, she spreads out their shots over a series of visits (paying the co-pay each time).

"The last round (Parker) got, he was kind of fussy and I could tell his legs were really sore after — just from the shots, so the next round I'll probably have them spaced apart because he didn't take this round so well," she says.

Olstad says her kids will be fully vaccinated when they start kindergarten, but knows delaying shots means they won't be protected from disease as quickly as possible. But, she isn't too worried about it.

"If he was going to be exposed to something it would be a concern," she says. "If there was a pertussis outbreak, I'd want to make sure he was vaccinated, but if there wasn't a big outbreak, I don't think it'd be a concern."

Some parents decide to delay their kids’ vaccines by a lot more.

Toby Hayes lives with his wife and six kids in Rancho Penasquitos. He followed the regular vaccine schedule for his oldest daughter Aiyana. Then she was diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome, an autism spectrum disorder.

Although research by British physician Andrew Wakefield that showed a link between vaccines and autism has been discredited, Hayes is still concerned the vaccines gave his daughter her disorder. So he decided to delay vaccinations for his other five children until they're 10 years old.

"It's a gut feeling, I can't describe it, but we were just uncomfortable with continuing on the regular schedule," he says. "At the end of the day, you have to weigh what's best for the individual child, for the individual family."

Hayes isn't as concerned about his kids getting the diseases vaccines are meant to protect against because those diseases don't completely feel real.

"We haven't seen the diseases, haven't seen what they do, so there's almost more of a visual toll on what the vaccines themselves will exact," he says.

Public Health Vs. Individual Concerns

Dr. Stuart Cohen, a pediatrician and president of the San Diego County Medical Society, says overall public health relies on the concept of "herd immunity." Because some kids can't get vaccines for medical reasons, and because vaccines are not 100 percent effective, herd immunity stops a disease from spreading.

"We're going to go back to the Dark Ages if we cross this tipping point on vaccine refusal," he says.

Cohen predicts there will be an outbreak of a disease like measles in San Diego County in the next few years. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently reported there have been at least eight measles outbreaks in the U.S. this year because of people who caught the disease in another country, returned to the U.S. and spread it to the unvaccinated.

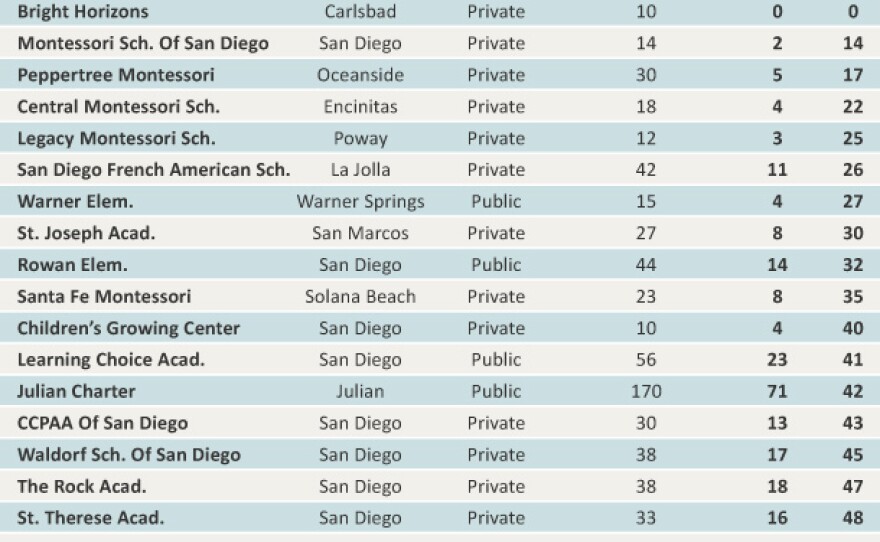

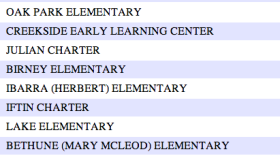

Many of the un- or undervaccinated kindergarteners in San Diego County are clustered at a small number of schools: More than half of the kindergarteners at 18 schools had either PBEs or conditional status.

Fifteen of the 20 schools in the county with the highest percentages of kindergarteners not up to date on vaccines last year were private schools, including five Montessori schools. Most were either in North County cities like Carlsbad, Oceanside, Encinitas and Poway, or in wealthier San Diego neighborhoods like Mission Hills and La Jolla. Some of the schools were in areas like Julian, Warner Springs and Chollas Creek. (See the full list below.)

Clusters of un- or undervaccinated kids at one school mean disease outbreaks could spread quickly, says Shane Crotty, a scientist at the La Jolla Institute for Allergy & Immunology. He says vaccines create tension between public health and individual concerns. Parents worried about vaccines' potential side effects want to protect their children, but the immunization system relies on all children following the set schedule.

"Not getting vaccinated is like littering," he says. "If one person does it, it's not a big deal, but if everybody does it, it becomes a really big problem."

Cohen, the medical society president, refuses to treat children whose parents insist on no vaccinations or delayed schedules. But other doctors, like Dr. Mary Anne Haskell, a pediatrician in Coronado, are happy to offer them.

As Haskell sits in her exam room crowded with stuffed animals, Russian stacking dolls and hanging mobiles, she says in the battle between public health and individual concerns, the latter wins.

"This isn't the public health perspective, this is an individual perspective," she says. "I believe that medicine is very hard to do as a one-size-fits-all. Almost all procedures in medicine and all medications and vaccines have a risk-to-benefit ratio, and you have to make the best decision for your family."

Crotty disagrees.

"This idea of spreading out the vaccines being a good idea is, I mean it's just a myth, and it's one of these myths that's gotten passed around," he says.

Vaccines are developed to be given on a specific timeline and giving multiple vaccines at one time is not harmful, Crotty says.

"Getting five vaccinations in a day is just a raindrop in the ocean of what your immune system deals with every day," he says.

Crotty says being partially vaccinated is better than not being vaccinated at all, but it still has risks.

"Not getting vaccinated on the regular schedule basically means that the child isn't protected from those infections as early as he could be," he says. "It's like having your kid wear a seatbelt. You don't have them wear the seatbelt because you're going to get in an accident today, it's because you want to be protected for all the times in the future you're going to be in the car, you just always wear the seatbelt."

'Leave It To The Experts'

The undervaccination trend worries parents like Anthony Wagner, who made sure his two kids followed the state's vaccine schedule.

"We leave it to the experts," he says, even though he feels bad about making his kids get multiple shots at the same time.

"Probably one of the hardest things that I had to do as a dad was hold my kid down while she looks at me and says 'why are you doing this to me?' while they give her a serum shot," he says. "Well that's hard to do, but the benefit of that far outweighs the crying, as well as the risk."

His decision is even fine with his daughter Maeve, who's in kindergarten at the St. Vincent de Paul school in Mission Hills.

In a soft voice, Maeve describes the bad memories from her last round of shots: "It really hurt and it was really painful," she says.

But clearly she’s been listening to her dad, and she makes a point for him. She gets shots, she says, "because we don't want the sickness from the sick people."