Walk through the streets of Barrio Logan and you quickly notice that it is a hodge-podge; From the vibrant murals of Chicano Park dancing on the underbelly of the freeway, to the shipyards that lace the waters edge, to residential housing tucked in next to industrial warehouses.

The tension between neighborhoods and business interests that has been highlighted in current city politics is perhaps nowhere better illustrated than in this complex mixed-use neighborhood.

Barrio Logan is in many ways a small slice of the city wedged between shipyards on one side and the freeway on the other and bisected by the towering Coronado Bridge, but the fight that has emerged regarding the update to the community plan here has pitted special interest groups against each other in a fierce battle.

On one side, you have the passionate activists of the Environmental Health Coalition, a group that seeks to address environmental racism. They’ve said the higher rates of asthma here — and even of cancer — represent the city of San Diego's blind eye to the largely low-income Latino population.

Maria Moya stood outside the Mercado housing projects, talking with a group of residents. Moya is a small woman with a round friendly face, her voice wavering between impassioned edict and giggling laughter.

She said this was the neighborhood the shipyards built, and the seeds of the struggle playing out today were sown in World War II when the American government brought in Mexican workers to man the shipyards.

“They needed the labor,” she said. “But there were restrictions on where people of color could live, so what did they do? They placed them in Barrio Logan.”

Barrio Logan was a neighborhood that served the building and restoring of ships. While the community settled in, so did maritime business. Without proper zoning regulations industrial-use businesses and houses grew up along side each other. The result? Polluted air that directly affected the residents.

Moya said the pollution got worse and the residents got sicker, yet for a long time nothing changed.

“It takes a lot of banging on the door and screaming and hollering for things to change in this community,” she said.

She said it was different here than in other parts of San Diego.

“If I lived in La Jolla and I have a little noise issue, that is taken care of right away," she said. "But here people have been screaming about their health and their children’s health and no ones listening.”

Only a few years ago, the exhaust pipes from plating factories ran directly into these low-income housing units. The residents who Moya talked to said it meant sick children and families with multiple miscarriages, not to mention cancer. But over time, things have changed for the better.

While driving me around Barrio Logan, Environmental Health Coalition’s Georgette Gomez said things have really changed since the heavy plating factories have left. As we pulled up on National Avenue, Gomez pointed out a converted factory.

“This used to be a heavy industrial master plating," she said. "It took us 10 years to get them shut down.”

She said the damage they did played out on the lungs of local children.

“They used to release hexochromium into the air, and literally their exhaust pipe was going right into these families homes,” she said.

Gomez is matter-of-fact when compared with Moya’s motherly tone, but Gomez pointed out details that come from having worked with the community for a long time. She remembered one 3-year-old who was particularly affected.

“He had to go to the hospital literally everyday to be able to breathe, 'cause it was really bad. Now that doesn’t happen just because they are no longer there," she said.

Things are better these days, Gomez said, but she said neighborhood zoning needs to really ratify those changes, and prepare a better future for residents of Barrio Logan.

Gomez said the problems today are less about direct pollutants seeping into the air and more about the storage of heavy chemicals. Gomez sounded weary as she pointed out one industrial commercial business after another. Signaling to a petroleum plant that just escapes the shadow of the Coronado Bridge she said, “These are heavy chemicals that are being stored there right in front of affordable housing — a housing project. To me it’s a — I don’t want it ever to happen — but it’s an accident waiting to happen.”

The other side in this debate — the shipyard and its business interests — also stand against what they agree is bad and incomplete zoning of a neighborhood that never could decide if it was residential or industrial.

Chris Wahl is spokesperson for the shipbuilding industry and the businesses that serve them. He said updating the community plan in Barrio Logan is a no-brainer.

“Everybody wants to have a better separation of uses, we are all on the same page on that," he said. "But it can’t be at the expense of the shipyards and their future.”

That is what places Wahl and those in the shipbuilding industry on the other side of the debate. He said most of the health issues the community faces have been resolved.

“The air,” he said “is now equal to the air in Poway.”

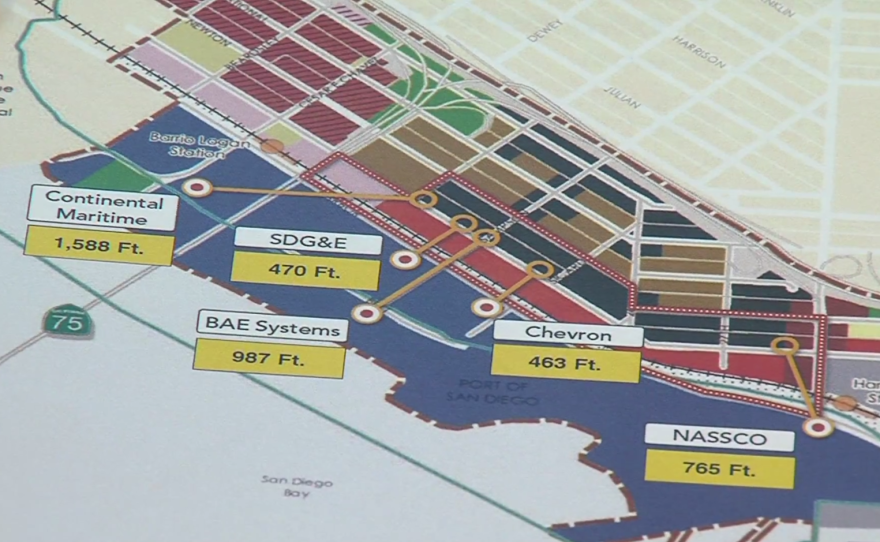

Wahl said that the shipbuilding enterprise and its interests have made serious concessions: They have given up greater than 50 percent of land that they once could have used.

He said the plan favored by community activists is not so much a buffer zone as it is a creeping of residential housing into the backyard of the shipbuilding industry.

“We would view it as a transition zone,” Wahl said and pointed out that the community's plan for a buffer zone is slated for houses, which he suspects would be an encroachment of residential homes into the shipyard's territory.

He worried 500 houses could be built just 1,000 feet away from the shipyards. Currently, In this contentious zone there are just about four houses.

The community members said they weren’t looking to build condos; Rather, they were trying to block the creation of commercial spaces that could allow for chemicals to be stored in the supposed buffer space.

But Wahl said by opening that space up to residential use it could move more homes and people closer and closer toward the port they were supposed to be buffeted against.

Wahl said the buffer should be made out of companies that already serve maritime industry.

President of the Port of San Diego Ship Repair Association, Derry Pence said that new development could gentrify the neighborhood and price out the low-income residents. Pence is also worried that kind of build-up could damageor even destroy the port.

“When you look out your window and all you see are cranes, you are not going to be a happy camper — that’s not what you paid for,” he said.

He said the buffer zone would protect the residents.

“If I can move you back a little bit, when you open the blinds you will see the beautiful blue sky of San Diego and other residential units, and life will be good," he said.

But opponents from the Environmental Housing Coalition said that idyllic picture is a red herring. They said the maritime plan would mean looking into the face of noxious noise and companies that could be storing chemicals on the lip of the residential plateau, no different than what they already see everyday.

In the end, the fight over zoning Barrio Logan has come down to a few square blocks. The resident activists want those blocks to be potentially residential while the maritime interests said they should be commerce that serves the port.

But Derry Pence said not to let the small square footage fool you.

“This is a very special area of San Diego, but that very special area of San Diego is not in a few blocks that we call Barrio Logan," he said. "It really impacts the entire region.”

Pence is referring to the larger impacts of maritime industry on the economy of San Diego, while the residents are talking about the blocks of space they call home.

The epic battle between neighborhood and economic interest may be playing out in a small space, but the question remains: how to resolve it?

City Councilman David Alvarez represents the neighborhood. He said he doesn’t want to stop industry from thriving in his home turf.

“We don’t want to encroach on industry cause those jobs are good jobs and we want to keep them. But we also don’t want to put industrial uses next door to somebody who lives in Barrio Logan or will live there in the future when development continues,” he said.

Activist Maria Moya agrees with the man she said she first met as a young boy from the Barrio. Moya is willing to concede having the buffer area zoned for houses. “You don’t want any houses there?” she said, “fine, but we don’t want any industries and that is what we are working out right now.”

Councilman Alvarez worried that misinformation is running rampant through Barrio Logan.

“We had residents call in saying they were told 'You will no longer be able to live here if the plan passes' — scare tactics are being used. This is a campaign, a well-financed campaign full of lies.”

Moya said she is hearing from shipyard workers who have heard that if the community plan passes, the shipyard giant NASCO will shut down.

“That is a lie,” she said.

Alvarez said what is happening in Barrio Logan represents a far larger citywide battle.

“This is the best example of the worst that San Diego has done in the past,” he said, referring to the lack of a community plan. But he said it is also “bringing about the worst of San Diego which is two special interests groups; One that is really well-funded and that is scaring people.”

Alvarez said co-existence between big industry and small neighborhoods is a delicate balance and it is one many parts of San Diego will soon have to face.

What is perhaps most surprising about this story isn’t how heated the battle is, it’s how much these two groups have managed to agree on. They’ve found middle ground on 93 percent of the community plan. Now, it’s up to San Diego City Council to see if they can do the same for the last few blocks of Barrio Logan — brokering a deal that keeps businesses thriving and a community feeling safe.