Stephen Jaime remembers when a patient showed up to his diabetes education classes with a giant soft drink cup. But instead of holding a sugary soda, the patient was packing something unexpected: insulin on ice.

His car didn’t have air conditioning, and he had to be out for hours in temperatures that could soar to 120 degrees, so he was managing with the resources he had.

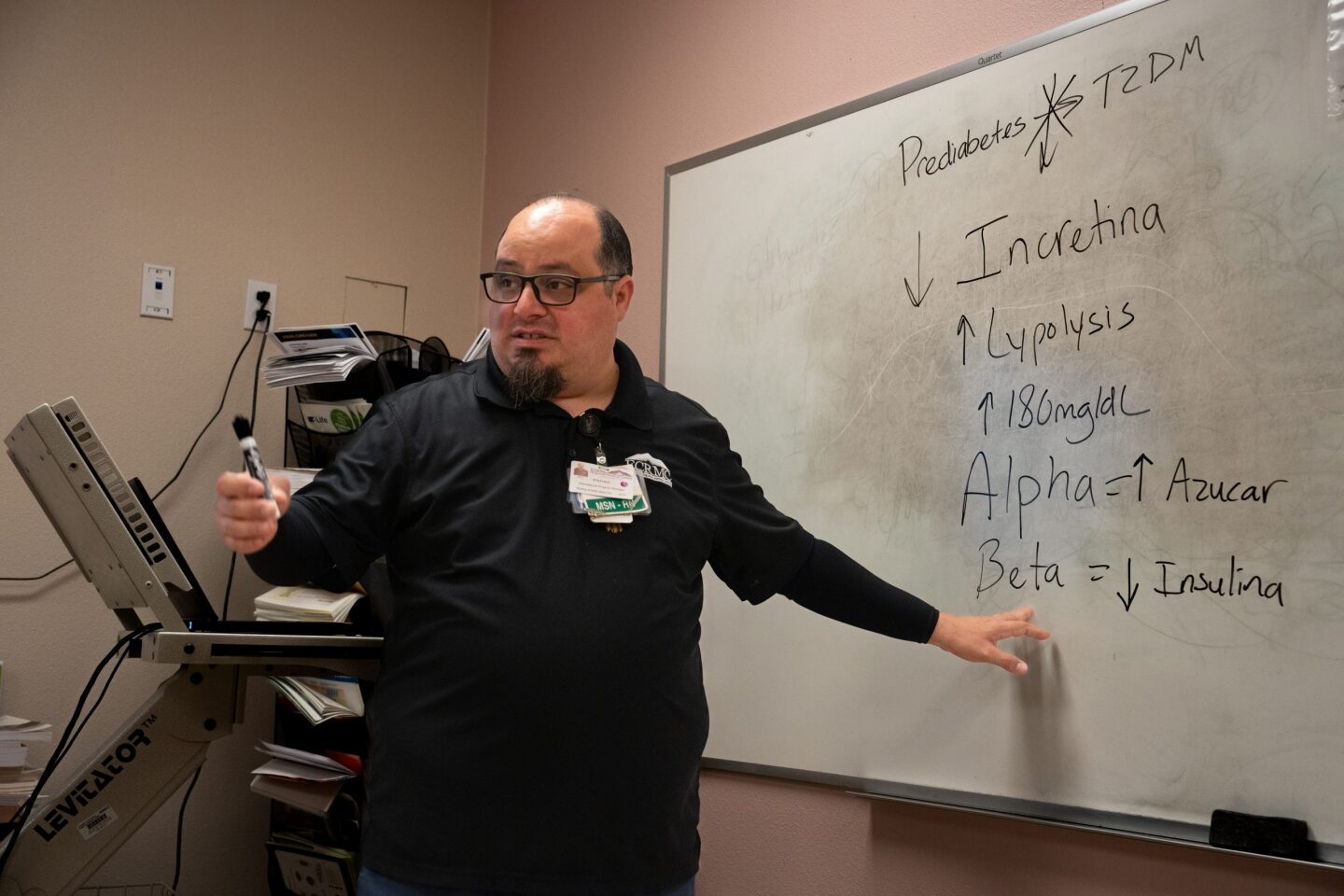

“Whatever works,” says Jaime, a career nurse who holds a doctorate in nursing science and now tells the story to diabetes patients attending his classes at El Centro Regional Medical Center in Imperial County.

As heat waves roll across the nation, medical researchers are sounding the alarm that extreme temperatures and climate change pose life threatening challenges to people with diabetes. The risks especially impact low-income communities. Medical professionals in Imperial County are echoing the concerns. There, for example, California’s highest diabetes rates collide with other factors that make managing the disease a challenge: periods of extreme heat and the highest unemployment rate in the state.

Diabetes patients on federal health insurance programs for the low-income and elderly commonly experience more complications when they live in areas experiencing extreme temperatures, according to a recent national study co-authored by Kacie Bogar, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Real-World Effectiveness and Safety of Therapeutics.

She also said that studies like theirs considering the impacts of climate change and health indicators have begun only recently, which means more research is needed to get a comprehensive look at the issue.

“There’s not enough data outlining what everyone seems to know at this point,” Bogar said.

Diabetes is a chronic disease that occurs when the body can’t regulate high blood sugar levels. The disease damages blood vessels, can cause nerve and organ damage and can lead to blindness, amputations and death.

In terms of medical factors, people with diabetes are more prone to heat illness and dehydration and may already be dealing with other health problems, including heart issues, that could be exacerbated by extreme heat.

“If you don't have a good heart, you can easily have a heart attack,” Dr. Majid Mani said, a diabetic eye surgeon in the Valley. “Mobility is very limited, unless you go very early in the morning or very late at night to walk … and not everybody can afford the gym.”

More than 70 people have died from heat related illness in Imperial Valley over the last three years. The community is still grieving the death of a 16-year-old girl who died late last month while running during her high-school physical education class. According to an online petition, the student collapsed after being forced to run. The temperature that day reached 112 degrees. The case is still under investigation.

In Imperial County, much of which is below sea level, summer high temperatures can reach 120 and rarely fall below the hundreds, and projections show extreme heat days will double throughout Southern California over the next 50 years with Imperial County taking the lead.

A multitude of socio-economic factors put residents at risk for poor health outcomes.

The county has among the lowest number of doctors per capitain the state, while the percentage of people living in poverty is almost double the state average. Residents have reported monthly AC bills in the $400 or $500 dollar range, taking up a significant portion of their paychecks. The median income in Imperial Valley is $53,900.

Meanwhile insulin, the drug used to manage diabetes, remains unaffordable for many. A recent federal policy has capped the price for those insured by Medicare, but it does not apply to those with private insurance.

“What if you make $1,500 (a month) … Can you imagine what this is doing to our community?” said Guadalupe Heredia, who founded the El Centro hospital diabetes education center in the 80’s.

Over half the county’s population relies on public health insurance. The service is crucial, but it has also heavily strained rural health care providers. Hospitals make more money by providing high cost services, many of which Imperial Valley hospitals can’t offer.

Heredia, who herself has diabetes and has devoted decades to educating and advocating for her community, says that all these factors together make up for a complex problem that can have deadly consequences for her neighbors.

“So you either pay your rent, eat or buy your medicine. Can you imagine that?” Heredia said.

Facing challenges

Frontline health workers in Imperial Valley supporting people with diabetes say the challenges residents face span from the level of health care access to the resources individual patients may have. A shortage of specialists, facilities as well as high costs of living are just some of the barriers.

Diabetes is a fact of life for many living in Imperial County. Recent data show 17% of the county’s population has been diagnosed with diabetes versus 11% statewide. The COVID-19 pandemic put additional stress on the local health care system while also raising awareness about the risks the disease poses to people with diabetes.

People with diabetes are more likely to develop serious complications from the virus. The pandemic, compounded with high heat and a shortage of medical facilities, the circumstances were particularly difficult in the Valley. Local hospitals had to set up tents to treat patients.

“In Imperial Valley it can go up to 120 degrees … can you imagine being in a tent?” Heredia said.

In extreme heat, Mani explained, people with diabetes can get so dehydrated that sugar levels surge and the person can have a stroke.

“The body's trying to compensate, get rid of the excess sugar, and then they get severely dehydrated,” Mani said. He said people often die in the middle of the night or in the morning, and families are not aware of the causes, but it can very well be a result of high heat and diabetes.

Heredia lost her brother who, like her, had longstanding diabetes when the pandemic struck. He spent several weeks in the hospital, came home and died in his sleep one month later from complications from diabetes and COVID-19.

“We were struggling as it was. But with that, it just tore it down,” Heredia said referring to the pandemic.

The pandemic heavily impacted hospital finances, and for El Centro Regional, debt accrued from retrofitting the facilities for earthquake preparedness came as another stressor. The hospital closed its maternity ward and pediatrics department.

The diabetes program has also suffered. Before the pandemic the diabetes education program had five staff members while now only two do the work.

After Heredia retired, Jaime, who has a doctorate in nursing science, now runs the education program. Jaime also has diabetes, is from Imperial Valley and focused his doctoral research on how to improve diabetes health care in the rural border region.

“So many people are sick that we just don't have enough providers for them,” Jaime said. “So I think that the high patient ratio is a big issue for what we have down here in the Valley.”

He said many of his patients don’t know important information that could help or even save their lives, like how to use a glucometer, the device that measures glucose levels.

“I've had so many patients come here, who were like, I don't even know how to use this thing, no one showed me.”

His research addresses how people of Hispanic background are more prone to developing the illness, and in what ways diabetes education can help decrease those numbers.

Diabetes rates are higher among Latinos than whites in the Valley. In San Diego County, 9.2% of Latinos and 7.5% of whites had been diagnosed with diabetes, while in Imperial County the numbers show a larger gap, with 17.1% and 12.5%, respectively.

Like Heredia, Jaime travels to Washington D.C. to advocate for his community, calling for resources to be funneled to places impacted like his own.

Imperial Valley’s Department of Public Health says that many cases of diabetes-related hospitalizations in the Valley could be prevented if there were overall improvements to the standard of living.

This includes access to affordable housing, transportation, parks, cooling centers and temperature-regulated exercise facilities.

It also means education in a language they can understand. Spanish is the first or only language spoken in many Imperial County homes.

“They're finally starting to come out with Spanish materials I can give my patients,” Jaime said. “The only problem is I need to make sure my patients can actually understand what they're reading.”

He says that means sitting down with them, taking some hours to trade stories and get to know them, share his own experience.

That takes time. And these days, Jaime says, he’s been busier than ever tending to patients.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on how to manage diabetes in high heat.

inewsource investigative reporter Philip Salata reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2024 California Fellowship.