The fumes that wandered into Martha Beatriz León’s preschool on the outskirts of Tecate, Mexico smelled way worse than usual, like rotting garbage. Or maybe it was ammonia. One woman compared it to spent gunpowder.

Whatever it was, León said it gave her a headache. Later that day in March 2022 her teachers began feeling sick, she said. Children throughout the neighborhood of San Pablo started vomiting.

“It was a hard day,” León said. “We didn’t know what was going on.”

On social media, warnings spread about a chemical release that came from behind the tall concrete and corrugated metal walls just across the road, a toxic waste recycling plant called Recicladora Temarry de Mexico.

Less than two miles across the border from inland San Diego County, Temarry is a startling example of how California exports the risk from its hazardous waste. The plant handles thousands of tons of the Golden State’s toxic detritus each year.

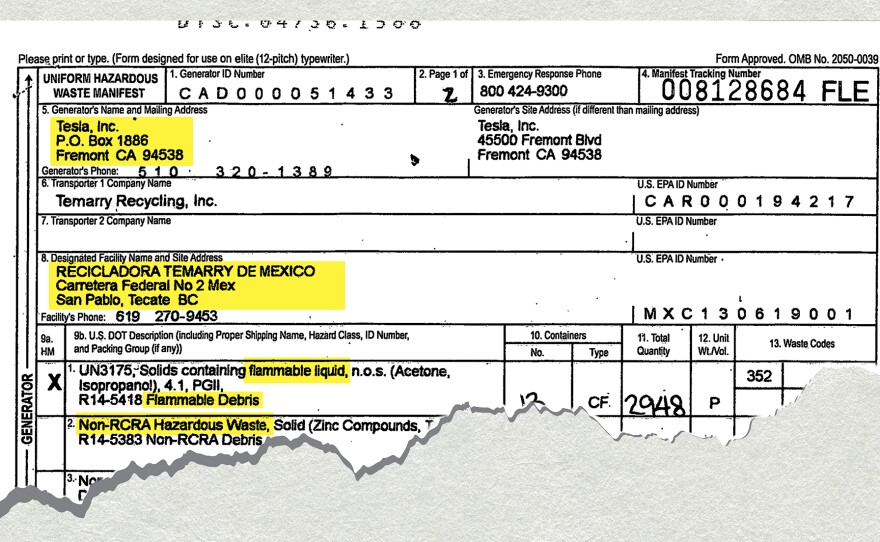

Here, Tesla has sent flammable liquids from its Bay Area manufacturing plant. Sally Beauty Supplies stores have gotten rid of old aerosols in Tecate, Sherwin-Williams has relied on Temarry to recycle its paint waste and the U.S. Navy has shipped its used solvents that can cause dizziness, nausea and respiratory failure.

California’s own government agencies have sent their waste here too, including old paint thinner from the state prisons and ink from the office that prints government forms.

As an ongoing CalMatters investigation has shown, California companies and government agencies have found it easier and far less expensive to avoid the Golden State’s strict environmental regulations by shipping the waste across state borders.

The result isn’t a cleaner environment. New reporting reveals that Temarry has faced allegations that it improperly handles materials that can cause serious damage to human health and the environment. In California court records, its former owner has been accused of illegally dumping waste in an open pit and misrepresenting on legal documents the type of waste exported to Mexico. And, in their public statements, Tecate’s mayor and top officials have suggested the company covered up the 2022 chemical release.

A lawyer for Temarry’s founder denied allegations the company mishandled waste under his supervision and referred questions on the March 2022 incident to the current owners, Massachusetts-based Triumvirate Environmental Inc. Triumvirate and its attorneys did not respond to multiple interview requests nor a detailed list of questions.

One of California’s top hazardous waste regulators acknowledged the state should be making sure its hazardous waste isn’t harming people outside of state lines.

“I think we have a responsibility to make sure our decisions here in the state – they don’t disproportionately impact other vulnerable communities and that may mean vulnerable communities in other countries,” said Katie Butler, the Department of Toxic Substances Control’s hazardous waste management program deputy director, speaking at a recent public event.

Asked if the department is doing that, she was unequivocal. “No,” Butler said.

Other department officials stress the limits of their authority. They can’t seal the borders, can’t cite companies outside of California and don’t have the legal authority to regulate interstate or foreign trade.

State officials have stonewalled CalMatters’ attempts to learn more about the waste California sends to Temarry, which also operates a transportation company in San Diego to handle exports. In March, we filed a California Public Records Act request for the records of all shipments sent to Temarry since 2019 (records before that had been available online). The department still hasn’t even formally responded to the request, something it’s required to do under law within 10 days. It’s been 289 days.

Following the request, shipping records that had shown up in an online search of the Mexico facility in the state’s public database suddenly disappeared – a loss of some 25,000 records from 2014 to 2018.

On paper, Mexico’s laws and regulations for handling hazardous waste are similar to those in the United States. And toxic waste facilities in California have certainly had their share of accidents and chemical releases. But advocates in Mexico blame corruption and limited resources for shoddy oversight.

“The whole world knows how things function in Mexico,” said Maria Magdalena Cerda Baez, a policy advocate with the Environmental Health Coalition, which has offices in National City and Tijuana and works on cross-border pollution issues. She said U.S. hazardous waste going to her country is unjust. “How can you be so rich and commit these crimes against people’s health and future?”

Authorities were first alerted to the odors coming from Temarry by a call from a nearby school, the mayor said on Facebook Live the night of the incident. Once the city’s top safety officials arrived, company representatives wouldn’t let them in to fully inspect, Tecate leaders alleged in press conferences. The city officials reported that Temarry workers were evacuating.

“We do not know what really happened,” Mayor Darío Benítez said at a press conference after the incident. “We’re left with the company’s version of events.”

Temarry’s deep California roots

Temarry’s story traces back to 1990 in Los Angeles when California toxic substances regulators ordered a place called Davis Chemical to stop handling hazardous waste.

The state was leading a national movement to regulate the handling of toxic and dangerous chemicals and Davis wasn’t keeping up with the times. Regulators found unlabeled drums, shoddy operations plans, and open and leaking containers, inspection records show. And it was treating hazardous waste without a permit.

After Davis Chemical closed, one of its operators’ grandchildren – Matthew Songer – opened a new solvent recycling business on the other side of the border. According to Temarry promotional material, he wanted to handle waste for some of the family’s old customers. Along with his then-wife and his uncle, Songer shipped the family’s equipment south to launch the new venture, and they mashed the names of three collaborators together to create a new company: Temarry.

Over the next two decades, Temarry worked to build an image as an environmentally friendly destination for hazardous waste, releasing reports and authoring blog posts with titles like “Can Hazardous Waste Be Part of the Circular Economy?” and “How to Achieve the Highest Level of Sustainability.” The company also touted the benefits of exporting waste in a report titled “How to Legally Transport Your Hazardous Waste to Mexico.”

The company’s specialty was recycling used solvents – the flammable, toxic liquids used for things like degreasing metal parts or removing nail polish. It’s waste that can explode and release toxic material into the air and groundwater if not properly handled.

It is big business. In 2021, federal records show Temarry Recycling took 6,099 shipments from its San Diego center to its Mexico affiliate – 31,237 metric tons of waste. The state’s tracking system lists only four facilities in California as having received more tons of hazardous waste that year.

When Matthew Songer and Teresita Ruiz Mendoza divorced, he sold the company for $25 million to Triumvirate Environmental in 2021. The Massachusetts company kept Songer on to run the operations for $550,000 a year with a bonus of up to $5 million over four years, according to his employment agreement, which was filed in court as part of a lawsuit.

What did he have to do for that bonus? Bring even more of America’s toxic trash across the border with Mexico to the Tecate neighborhood of San Pablo, a community of small homes and two-story apartments in neat rows surrounded by scrubland and the industrial sites that employ many of the residents.

Residents there said they’ve long been accustomed to chemical smells filling the neighborhood, sometimes leaving them with headaches.

But the fumes of March 24, 2022, seemed worse to them. Families didn’t know what to do as chemical vapors wafted across the two-lane federal highway separating the homes from Temarry. Some holed up – closing windows and wearing the masks they had for COVID. The fortunate fled. Maria Ayón and her family left town for the weekend.

Not everyone could. “They didn’t have anywhere else to go,” Ayón said.

Gloria Romero said she rushed home from work when she heard there was some sort of incident.

“I took my daughters – locked my house, locked up my pets,” she said. Her girls were sick for days, Romero said, and she worries about their long-term health. “Even when there’s no leak it sometimes smells a lot like ammonia.”

León, the preschool principal, said one of her students “was very sick for a week and a half with diarrhea and vomiting.”

Benítez, the Tecate mayor, has been highly critical of the way Temarry officials handled the leak. He alleged the company didn’t call emergency services to report the accident.

That night, Benítez held a press conference at Tecate’s Palacio Municipal. Sitting behind a long table next to a city environmental inspector and other officials, the mayor said he’d been told 16 barrels of hydrogen sulfide spilled. “How do you simultaneously spill sixteen drums of hydrogen sulfide?” he said.

Benítez said he was also told another story – that some sort of chemical reaction on site released fumes, suggesting Temarry was covering up what really happened.

The chemical release generated local media coverage in Mexico. Reporters there revealed the company had been the site of a 2010 explosion that injured a worker.

Tecate officials ordered Temarry to shut down. In a press release posted online, the city’s fire chief, Enrique García, is quoted as saying that an inspection of the site after the 2022 incident found “critical anomalies … that put the company at risk of fire, in addition to toxic spills.”

Benítez accused a top Baja state official of pressuring him to let the site keep operating. Eventually, a judge allowed Temarry to reopen.

The chemical leak became an international incident. In May 2022, U.S. Consul General Thomas E. Reott visited Benítez to talk about Temarry. The mayor posted about it on Facebook, sharing a photo of Reott watching him strum a guitar.

California’s regulators won’t get involved

More recently, allegations made in California courts raise the question whether the March 2022 incident was part of a pattern of mishandling hazardous waste.

Songer sued Triumvirate after it fired him in June 2023. Songer was actually on leave at the time of the chemical release, according to his attorney. The company filed a counterclaim accusing the former Temarry president of fraud.

In a copy of his termination letter filed in court, the company wrote that Songer was being fired for among other things “misrepresenting on legal documents the type of waste [he] exported from the United States to Mexico” and for “authorizing and directing the illegal dumping of waste at unauthorized facilities in Mexico, including in March, 2022.”

Triumvirate says equipment at Temarry’s Mexico facility was “not in good operating condition” at the time Songer sold them the company. The equipment was “woefully inadequate to test, analyze and process the waste as represented. Further, the Mexican Recycling Facility was incapable of achieving anywhere near the recycling and processing levels” listed in documents at the time of the sale, according to the counterclaim.

Triumvirate personnel also witnessed Songer in March last year direct a tanker load of waste to an unauthorized location in Mexico and had the driver “dump the waste into an open pit,” the company alleges in court filings.

Songer’s attorney, H. Troy Romero, said his client denies the allegations but declined to provide details because of the ongoing litigation.

Records show state and federal regulators have inspected Temarry’s U.S.-based operations over the years. The company entered into a consent agreement with the Environmental Protection Agency in 2014 after the feds accused Temarry of exporting unauthorized waste to Mexico. In 2016, California toxics regulators cited Temarry for exporting waste that it hadn’t listed in a report to the state. And in 2021 the state cited Temarry’s San Diego-based transporter for keeping hazardous waste in its California facility for too long before shipping it off.

Carlo Rodriguez is a top California Department of Toxic Substances Control enforcement official who works on border issues in San Diego, where Temarry’s export hub is located. He said it’s up to Mexican authorities to oversee Temarry’s operations on the other side of the border.

“We trust them,” Rodriguez said. “We have to trust them so there can be a working relationship.”

While it’s true California regulators’ authority ends at the border, officials have long found creative ways to go after contamination and other environmental issues seemingly outside their jurisdiction – crafting incentive-based programs or using enforcement powers to go after operations that pass through the state. And while no actual wrongdoing has been proven on the part of Temarry, there remain open questions about how the company is handling California’s toxic waste – and the state seems uninterested in trying to get answers.

“If you want to close a blind eye and say once it crosses the border it doesn’t concern me anymore. Whatever they do or don’t do, that’s their problem. You can always take that attitude. That’s a typical government bureaucracy approach. The lazy, I don’t give a damn approach,” said David Eng, a retired Los Angeles County prosecutor who used transportation-related statutes in the early 90s to go after pollution in Tijuana. “I saw a catastrophe – and I wanted to do everything I could to stop it.”

Back on the dusty streets of the San Pablo neighborhood in Tecate, residents worry about their health, and the health of their children.

“We know there’s some risk,” said Maria Ayón, who had fled the neighborhood during the leak. “Those smells aren’t normal. When you get headaches, when you get dizzy or start to vomit, it’s because something bad is happening over there.”

Reporting contributed by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., Jeremia Kimelman and Shreya Agrawal