The San Diego Unified School District has made changes to its Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps since Chicano students began campaigning for reform in 2008.

They removed shooting ranges from schools, and last year they began requiring a consent form on file for every participating student.

But San Diego Chicano/Latino Concilio on Higher Education leaders still have concerns.

They sent a letter to the Board of Education this summer, stating the form still doesn't provide students with all the information needed for fully informed consent.

It doesn’t specify that JROTC doesn’t meet any of the A-G requirements for California’s public universities, or that it’s taught by retired military officers.

Jennifer Roberson, senior director of the district’s Office of Graduation, said this year’s consent form was already distributed to schools, but they’re open to continuing conversations and possible changes to the form’s language for next year.

She said JROTC exists because students want it.

“Students are opting to be in the program. They know that it's voluntary, it's not required. But we do believe that the skills that they're being taught do prepare them to be future ready,” she said.

She said the district does work with schools to increase enrollment in JROTC when it falls below the minimum required to keep the program.

The military-sponsored class offers three days per week of physical education, one day of training on skills like leadership, financial literacy and first aid, and one day where students practice drills and marching in uniform.

Morse High School senior and JROTC member Joseph Cruz said JROTC gave him much-needed initiative after graduating middle school during the pandemic left him feeling lost.

“It’s given me the initiative I needed to pursue greater things,” he said.

In his sophomore year, he was chosen to lead about 50 students as Company First Sergeant.

“Being able to have that daily exposure as a leader, having that experience, it's really built me up,” he said.

He’s considering studying law at a military academy to pursue a dream career of being a judge advocate general (JAG) officer.

He said recruiters come to his class often to talk about the wide range of careers in the military and their benefits.

Retired Lt. Col. Mark Ayson, Hoover High’s senior army instructor, said JROTC did start as a recruiting tool, but evolved after the Vietnam War into “more of a leadership development class.”

School staff emphasize the class is about leadership and character development, not military recruitment.

But the effect might be the same.

Last year, an Army-sponsored study found that Army JROTC students are less likely to enroll in college after graduating high school, and those who don’t are more likely to join the military.

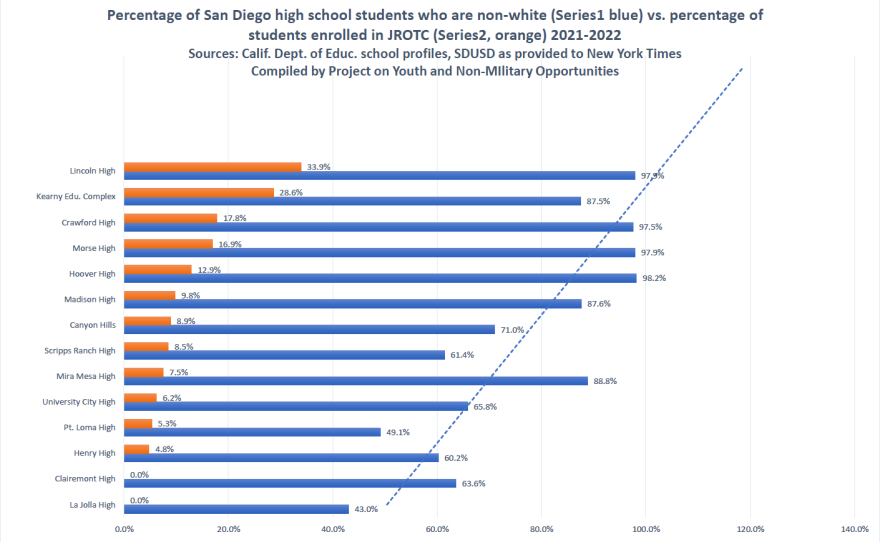

That’s concerning to local Chicano community leaders, because in the San Diego Unified school district, schools with a higher percentage of nonwhite students have much higher rates of JROTC enrollment.

The Project on Youth and Non-Military Opportunities analyzed school district enrollment data for 2022.

At Lincoln High — where nearly all students are nonwhite — more than a third of students enrolled in JRTOC.

At majority-white Point Loma High, that rate was just 5%.

La Jolla High, in one of the district’s wealthiest neighborhoods, doesn’t have a JROTC program.

Davíd Morales was part of the student movement against JROTC in 2008.

Now, he’s a counter-recruitment activist, pursuing a Ph.D. in racial inequalities in education at Stanford.

He said there’s a reason JROTC programs have lower enrollment at schools in wealthier neighborhoods.

“You have parents who are much more involved because they have the means and privilege to be involved and aware of what's happening. And they're not going to stand for their kids being constantly harassed by military recruiters or being pitched a job in the military,” he said.

He said students in lower-income areas are also more susceptible to what he called the deception of military recruiters.

“It is true that for some people, some communities, the options are limited, and that's unfortunate. And they are very much more open to being, or likely are easier to target by recruiters because of this situation. We think this is predatory,” he said. “We've called this a Poverty Draft in some cases.”

He said alternatives to JROTC should be explored.

“There are other ways to engage in practice discipline that do not include weapons and blindly obeying and following orders that instead encourage critical thinking skills,” he said. “That does not include careers in war-making.”

“We must instead focus on careers for peace and social justice,” he said.

His sentiments were shared by other local members of the Project on Youth and Non-Military Opportunities and the Chicano/Latino Concilio on Higher Education.

They are calling for an evidence-based review of the effectiveness of the JROTC program.