Choosing whether to buy a portable classroom or build a permanent school building seems to be an uncomplicated decision, if you’re just considering time and money.

The bill for portables can be less than half the cost per square foot of a traditional brick-and-mortar building, and they can be up and running as much as a full year before a permanent one.

But the savings aren’t what they seem to be, said Dede Alpert, a former state lawmaker from Solana Beach who focused largely on education during her 14-year career in the Legislature.

As portables became more permanent, parents and school administrators started asking for nicer — and therefore more expensive — options.

RELATED: Portable Classrooms Find Permanent Home In San Diego County Despite Heat, Noise

“A lot of people began to say, ‘They’re not cheaper, they’re not portable and maybe it’s actually dangerous to the health of children if they have to be in these buildings all the time,’” she said.

School economics

There was a time in California when portables were required. During most of the 1990s, the state said all new school construction using state money must consist of at least 30 percent portable classrooms.

The idea was portables would be cheaper for districts, with the added advantage that they could be moved around as needed, said Lee Dulgeroff, facilities chief at the San Diego Unified School District. They were also an easy answer to class-size reduction, a big push in the 1990s.

The Legislature changed that rule in 1998, but it left an incentive for school districts to maintain a certain share of portables. If they had portables, they could collect larger fees from developers to make up for the burdens new home construction had on schools.

Some of those decades-old portables are still used.

Alpert has seen them.

“I’ve been in San Diego Unified in some of these portable buildings, which are, well, they’re almost disgraceful,” she said. “They’re so old, and you know they look awful. They really detract from the appearance.”

Advantages for districts

One of the main selling points for portables is their relative low cost.

Caroline Brown, executive director for capital projects at the Solana Beach School District, saw that advantage at her district.

“(Portables are the) fastest, least expensive way to get some classrooms out there until we can figure out how to get more permanent structures,” Brown said.

Tom Duffy, a legislative advocate for the Coalition for Adequate School Housing, a school construction industry trade group in California, has numbers to support that statement.

In general, Duffy said, a traditional classroom can cost from $180 or $200 a square foot for portables to about $350 or $400 a square foot for permanent classrooms.

Portables might be cheaper at first, but in the long term they can cost more than permanent classrooms when energy and maintenance costs are included.

“You have to maintain them a lot sooner than you do a permanent building,” Brown said. For some portables, that means a new roof, ceiling tiles, carpet and maybe replacing the outer wall.

They’re cheaper at the beginning, but in the long run it can be as expensive as building a permanent building in the first place, Brown said. In just one school, Solana Vista Elementary, some portables are almost 30 years old and need to be completely remodeled. Two out of three classrooms at the school are portables.

“Pay now or pay later, right?” she said.

Energy costs can be a huge drain on district finances. San Diego County districts are facing a $30 million increase in utility costs from San Diego Gas & Electric.

An inewsource investigation last year found that a large share of school electricity bills are because of surge pricing from sudden heat waves or cold snaps that ramp up AC and heater use. Those temperature spikes could be exacerbated by the notoriously poor insulation in portables.

Documents obtained by inewsource for that investigation showed surge pricing accounted for more than half of one San Diego Unified high school’s $70,000 one-month electricity bill.

The test of time

The second popular selling point for portables is how quickly they can be set up. Adding a permanent classroom takes about 2½ years from planning to completion, Dulgeroff said.

Portable structures, on the other hand, are often pre-designed and approved by the state. They can be up and running in about a year and a half.

Portables also can be brought on incrementally. If a high school needs a new English classroom, it doesn’t have to wait for money and approval to construct a whole building.

“When you plan a new classroom building, you’re planning, you know, four or six or eight classrooms at a time,” Dulgeroff said. Portables can come in packs, or they can be purchased one at a time.

Quick addition of new classrooms has allowed districts to handle rapidly changing demographics.

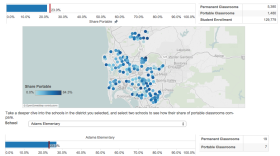

Enrollment has historically been a roller coaster at San Diego Unified, Dulgeroff said. It grew about 30 percent in the 1960s and 1970s, then declined during the 1980s to about 110,000 students. It then went through a second boom, peaking at about 142,000 students in 2000.

The district is down to fewer than 130,000 students.

“Portable classrooms were, I think, one means of dealing with demographic shifts,” Dulgeroff said.

The theory in the early days was that districts could pick up and move portables to meet changing demand in specific schools. That did happen in some instances, but Alpert said, portable “is really such a misnomer.”

“Once they went on a site and when they were properly anchored, they were there to stay,” she said. “You didn’t just one day pick them up and move them two days later to another campus.”

In Solana Beach, Brown said the school board is considering a bond measure this fall that could be used to replace all the portables at three schools, including Solana Vista Elementary.

Duffy, with the construction trade group, can see a future where districts use more, not fewer portable or modular classrooms. Newer models, he said, are hard to distinguish from permanent structures.

“There’s a high school in Sacramento that is probably more than 15 minutes, 20 minutes from my office, that was put in place in a period of about nine months,” he said. “It is an entirely modular high school.”

Alpert said more emphasis needs to be put into what schools should look like in the future, and what facilities and technologies will benefit students the most.

She points at textbooks schools keep buying that teachers don’t use, or a rush in the 1990s by President Bill Clinton to hardwire all schools, which became useless as more technology became wireless.

“What is a school going to look like in 20 years?” Alpert said. “I see with my grandchildren that learning is so different from when I was in school.”

We want to hear from you: Tell us what you think about portable classrooms at schools.

Investigative Assistant Madison Hopkins contributed to this report.